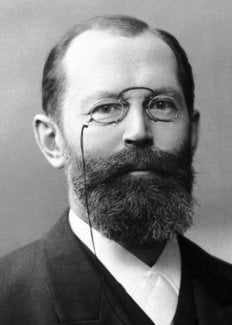

Emil Fischer

Biographical

Hermann Emil Fischer was born on October 9, 1852, at Euskirchen, in the Cologne district. His father was a successful business man. After three years with a private tutor, Emil went to the local school and then spent two years at school at Wetzlar, and two more at Bonn where he passed his final examination in 1869 with great distinction. His father wished him to enter the family lumber business, but Emil wished to study the natural sciences, especially physics and, after an unsuccessful trial of Emil in the business, his father – who, according to the laureate’s autobiography, said that Emil was too stupid to be a business man and had better be a student – sent him in 1871 to the University of Bonn to study chemistry. There he attended the lectures of Kekulé, Engelbach and Zincke, and also those of August Kundt on physics, and of Paul Groth on mineralogy.

In 1872, however, Emil, who still wished to study physics, was persuaded by his cousin Otto Fischer, to go with him to the newly established University of Strasbourg, where Professor Rose was working on the Bunsen method of analysis. Here Fischer met Adolf von Baeyer, under whose influence he finally decided to devote his life to chemistry. Studying under von Baeyer, Fischer worked on the phthalein dyes which Rose had discovered and in 1874 he took his Ph.D. at Strasbourg with a thesis on fluoresceine and orcin-phthalein. In the same year he was appointed assistant instructor at Strasbourg University and here he discovered the first hydrazine base, phenylhydrazine and demonstrated its relationship to hydrazobenzene and to a sulphonic acid described by Strecker and Römer. The discovery of phenylhydrazine, reputed to have been accidental, was related to much of Fischer’s later work.

In 1875 von Baeyer was asked to succeed Liebig at the University of Munich and Fischer went there with him to become an assistant in organic chemistry.

In 1878 Fischer qualified as a Privatdozent at Munich, where he was appointed Associate Professor of Analytical Chemistry in 1879. In the same year he was offered, but refused, the Chair of Chemistry at Aix-la-Chapelle. In 1881 he was appointed Professor of Chemistry at the University of Erlangen and in 1883 he was asked by the Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik to direct its scientific laboratory. Fischer, however, whose father had now made him financially independent, preferred academic work.

In 1888 he was asked to become Professor of Chemistry at the University of Würzburg and here he remained until 1892, when he was asked to succeed A. W. Hofmann in the Chair of Chemistry at the University of Berlin. Here he remained until his death in 1919.

Fischer’s early discovery of phenylhydrazine and its influence on his later work have already been mentioned. While he was at Munich, Fisher continued to work on the hydrazines and, working there with his cousin Otto Fischer, who had followed him to Munich, he and Otto worked out a new theory of the constitution of the dyes derived from triphenylmethane, proving this by experimental work to be correct.

At Erlangen Fischer studied the active principles of tea, coffee and cocoa, namely, caffeine and theobromine, and established the constitution of a series of compounds in this field, eventually synthesizing them.

The work, however, on which Fischer’s fame chiefly rests, was his studies of the purines and the sugars. This work, carried out between 1882 and 1906 showed that various substances, little known at that time, such as adenine, xanthine, in vegetable substances, caffeine and, in animal excrete, uric acid and guanine, all belonged to one homogeneous family and could be derived from one another and that they corresponded to different hydroxyl and amino derivatives of the same fundamental system formed by a bicyclic nitrogenous structure into which the characteristic urea group entered. This parent substance, which at first he regarded as being hypothetical, he called purine in 1884, and he synthesized it in 1898. Numerous artificial derivatives, more or less analogous to the naturally-occurring substances, came from his laboratory between 1882 and 1896.

In 1884 Fischer began his great work on the sugars, which transformed the knowledge of these compounds and welded the new knowledge obtained into a coherent whole. Even before 1880 the aldehyde formula of glucose had been indicated, but Fischer established it by a series of transformations such as oxidation into aldonic acid and the action of phenylhydrazine which he had discovered and which made possible the formation of the phenylhydrazones and the osazones. By passage to a common osazone, he established the relation between glucose, fructose and mannose, which he discovered in 1888. In 1890, by epimerization between gluconic and mannonic acids, he established the stereochemical nature and isomery of the sugars, and between 1891 and 1894 he established the stereochemical configuration of all the known sugars and exactly foretold the possible isomers, by an ingenious application of the theory of the asymmetrical carbon atom of Van’t Hoff and Le Bel, published in 1874. Reciprocal syntheses between different hexoses by isomerization and then between pentoses, hexoses, and heptoses by reaction of degradation and synthesis proved the value of the systematics he had established. His greatest success was his synthesis of glucose, fructose and mannose in 1890, starting from glycerol.

This monumental work on the sugars, carried out between 1884 and 1894, was extended by other work, the most important being his studies of the glucosides.

Between 1899 and 1908 Fischer made his great contributions to knowledge of the proteins. He sought by analysis effective methods of separating and identifying the individual amino acids, discovering a new type of them, the cyclic amino acids: proline and oxyproline. He also studied the synthesis of proteins by obtaining the various amino acids in an optically-active form in order to unite them. He was able to establish the type of bond that would connect them together in chains, namely, the peptide bond, and by means of this he obtained the dipeptides and later the tripeptides and polypeptides. In 1901 he discovered, in collaboration with Fourneau, the synthesis of the dipeptide, glycyl-glycine and in that year he also published his work on the hydrolysis of casein. Amino acids occurring in nature were prepared in the laboratory and new ones were discovered. His synthesis of the oligopeptides culminated in an octodecapeptide, which had many characteristics of natural proteins. This and his subsequent work led to a better understanding of the proteins and laid the foundations for later studies of them.

In addition to his great work in the fields already mentioned, Fischer also studied the enzymes and the chemical substances in the lichens which he found during his frequent holidays in the Black Forest, and also substances used in tanning and, during the final years of his life, the fats.

Fischer was made a Prussian Geheimrat (Excellenz), and held honorary doctorates of the Universities of Christiania, Cambridge (England), Manchester and Brussels. He was also awarded the Prussian Order of Merit and the Maximilian Order for Arts and Sciences. In 1902 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on sugar and purine syntheses.

At the age of 18, before he went to the University of Bonn, Fischer suffered from gastritis, which attacked him again towards the end of his tenure of the Chair at Erlangen and caused him to refuse a tempting offer to follow Victor Meyer at the Federal Technical University at Zurich and to take a year’s leave of absence before he went, in 1888, to Würzburg. Possibly this affliction was the forerunner of the cancer from which he died.

Throughout his life he was well served by his excellent memory, which enabled him, although he was not a naturally good speaker, to memorize manuscripts of lectures that he had written.

He was particularly happy at Würzburg where he enjoyed walks among the hills and he also made frequent visits to the Black Forest. His administrative work, especially when he went to Berlin, revealed him as a tenacious campaigner for the establishment of scientific foundations, not only in chemistry, but in other fields of work as well. His keen understanding of scientific problems, his intuition and love of truth and his insistence on experimental proof of hypotheses, marked him as one of the truly great scientists of all time.

In 1888 Fischer married Agnes Gerlach, daughter of J. von Gerlach, Professor of Anatomy at Erlangen. Unhappily his wife died seven years after their marriage. They had three sons, one of whom was killed in the First World War; another took his own life at the age of 25 as a result of compulsory military training. The third son, Hermann Otto Laurenz Fischer, who died in 1960, was Professor of Biochemistry in the University of California at Berkeley.

When Fischer died in 1919, the Emil Fischer Memorial Medal was instituted by the German Chemical Society.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Emil Fischer died on July 15, 1919.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.