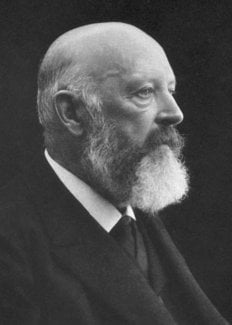

Adolf von Baeyer

Biographical

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer was born on October 31, 1835, in Berlin, as the son of Johann Jakob Baeyer and Eugenie née Hitzig. He came from a family distinguished both in literature and the natural sciences. His father, a lieutenant-general, was the originator of the European system of geodetic measurement. Even as a child Baeyer was interested in chemical experiments and at the age of twelve found a new double salt of copper.

Baeyer devoted his first two years as a student at the University of Berlin (1853-1855) chiefly to physics and mathematics. By 1856, however, his old love for chemistry re-awakened and drew him to Bunsen’s laboratory in Heidelberg. His studies here on methyl chloride resulted in his first published work which came out in 1857. During the next year he worked in Kekulé’s private laboratory in Heidelberg and was associated with his ingenious structure theory. Baeyer’s life work was soon to bring this indeed most brilliant of chemical theories much resounding success. In 1858, in Berlin, he received his doctorate for his work on cacodyl compounds which had been done in Kekulé’s laboratory.

For the next year or two Baeyer was again working with Kekulé who had meanwhile become Professor at Ghent. A study of uric acid, which also led him to the discovery of barbituric acid, provided the thesis by which he qualified as a university teacher in 1860. In the same year he became a lecturer in organic chemistry at the “Gewerbe-Akademie” (Trade Academy) in Berlin. He received little money but was given a spacious laboratory. In 1866 the University of Berlin, at the suggestion of A.W. Hofmann, conferred on him a senior lectureship, which, however, was unpaid.

It was during the Berlin period that Baeyer began most of the work that was to bring him fame later. In 1865 he started his work on indigo – the blue dye had fascinated him since his youth-and this soon led to the discovery of indole and to the partial synthesis of indigotin. His pupils Graebe and Liebermann, with the help of the zinc-dust distillation developed by Baeyer, clarified the structure of alizarin and worked out the synthesis used industrially. Studies were initiated on condensation reactions which, after Baeyer had gone to Strassburg as Professor in the newly established University (1871) brought to light that important category of dyestuffs – the phthaleins. Baeyer’s theory of carbon-dioxide assimilation in formaldehyde also belongs to this period.

On the death of Justus von Liebig in 1873, Baeyer was called to his Chair in the University of Munich and there, over many years, built up an excellent new chemical laboratory. With his tenure at Munich came elegant total syntheses of indigo, as well as work on acetylene and polyacetylene, and from this derived the famous Baeyer strain theory of the carbon rings; there were studies of the constitution of benzene as well as comprehensive investigations into cyclic terpene. In this connexion the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of ketones by means of per-acids was discovered. Especial interest was aroused theoretically by his work on organic peroxides and oxonium compounds and on the connexion between constitution and colour.

Von Baeyer’s work was at once pioneering and many-sided. With admirable penetration and extraordinary experimental skill he combined dogged perseverance and, even at 70 years old, a youthful buoyancy in his work. He was careful never to overestimate the value of a theory. While Kekulé sometimes approached Nature with preconceived opinions, von Baeyer would say: “I have never set up an experiment to see whether I was right, but to see how the materials behave”. Even in old age his views did not become fixed, and his mind remained open to new developments in chemical science.

Like Berzelius and Liebig, von Baeyer distinguished himself by forming a school which alone nurtured fifty future university teachers. Honours were heaped upon him, including the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1905. On his fiftieth birthday he was raised to the hereditary nobility.

Adolf von Baeyer married Adelheid (Lida) Bendemann in 1868. They had one daughter, who became the wife of the chemist Oskar Piloty, and two sons, both university lecturers, Hans in medicine at Munich, and Otto in physics at Berlin. He was still young in spirit when he succumbed to a seizure at his country house at Starnberger See on August 20, 1917.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.