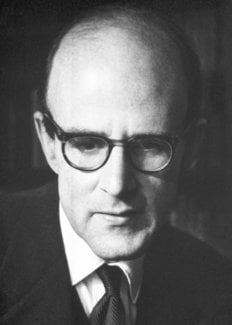

Max F. Perutz

Biographical

Max Ferdinand Perutz was born in Vienna on May 19th, 1914. Both his parents, Hugo Perutz and Dely Goldschmidt, came from families of textile manufacturers who had made their fortune in the 19th century by the introduction of mechanical spinning and weaving into the Austrian monarchy. He was sent to school at the Theresianum, a grammar school derived from an officers academy of the days of the empress Maria Theresia, and his parents suggested that he should study law in preparation for entering the family business. However, a good schoolmaster awakened his interest in chemistry, and he had no difficulty in persuading his parents to let him study the subject of his choice.

In 1932, he entered Vienna University, where he, in his own words, “wasted five semesters in an exacting course of inorganic analysis”. His curiosity was aroused, however, by organic chemistry, and especially by a course of organic biochemistry, given by F. von Wessely, in which Sir F.G. Hopkins’ work at Cambridge was mentioned. It was here that Perutz decided that Cambridge was the place where he wanted to work for his Ph.D. thesis. With financial help from his father he became a research student at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge under J.D. Bernal in September 1936, and he has stayed at Cambridge ever since.

After Hitler’s invasion in Austria and Czechoslovakia, the family business was expropriated, his parents became refugees, and his own funds were soon exhausted. He was saved by being appointed research assistant to Sir Lawrence Bragg, under a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, on January 1st, 1939. The grant continued, with various interruptions due to the war, until 1945, when Perutz was given an Imperial Chemical Industries Research Fellowship. In October 1947, he was made head of the newly constituted Medical Research Council Unit for Molecular Biology, with J.C. Kendrew representing its entire staff. He continued holding this post until he was made Chairman of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, in March 1962. His collaboration with Sir Lawrence Bragg has continued through all these years.

The scientific work of Perutz on the structure of haemoglobin started as a result of a conversation with F. Haurowitz in Prague, in September 1937. G.S. Adair made him the first crystals of horse haemoglobin, and Bernal and I. Fankuchen showed him how to take X-ray pictures and how to interpret them. Early in 1938, Bernal, Fankuchen, and Perutz [Nature, 141 (1938) 523] published a joint paper on X-ray diffraction from crystals of haemoglobin and chymotrypsin. The chymotrypsin crystals were twinned and therefore difficult to work with, and so Perutz continued with haemoglobin. D. Keilin, then Professor of Biology and Parasitology at Cambridge, soon became interested in the work and provided Perutz and his colleagues with the biochemical laboratory facilities which they lacked at the Cavendish. Thus from 1938 until the early fifties the protein chemistry was done at Keilin’s Molteno Institute and the X-ray work at the Cavendish, with Perutz busily bridging the gap between biology and physics on his bicycle. The rest of the story is well-known and forms the subject of his Nobel discourse.

Perutz has persued one sideline concerned with glaciers, studying their crystal texture and mechanism of flow, but this was mainly an excuse for working in the mountains: he is a keen mountaineer, his other recreations being walking, skiing and gardening. Scientifically, his overwhelming interest lies on the side of molecular biology. He is grateful for having had the good fortune of being joined by colleagues of great ability, several of whom have now been honoured with the Nobel Prize at the same time as Perutz himself. Kendrew came in 1946, Crick in 1948, and Watson arrived as a visitor in 1951. Recently F. Sanger, who received the Nobel Prize in 1958, also joined forces with them. Perutz is extremely happy at the generous recognition given by the Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Royal Karolinska Institute to their great common adventures and hopes that it will spur them to new endeavours.

Perutz, who is a Fellow of the Royal Society, was made Commander of the British Empire in 1962. He is also an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In 1942, Perutz married Gisela Peiser. They have two children, Vivien (b. 1944) and Robin (b. 1949).

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Max F. Perutz died on February 6, 2002.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.