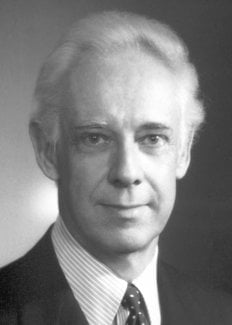

Stanford Moore

Biographical

Stanford Moore was born in 1913 in Chicago, Illinois, and grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, where his father was a member of the faculty of the School of Law of Vanderbilt University. His developmental years were in a home environment which made the pursuit of knowledge an eagerly adopted undertaking. He had the opportunity to attend a high school administered by the George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville. A skilled teacher of science, R.O. Beauchamp, kindled an interest in chemistry. Moore entered Vanderbilt University undecided between a career in chemistry or aeronautical engineering. The courses which he took in the engineering school presaged a concern for instrumentation. But a gifted professor of organic chemistry, Arthur Ingersoll, succeeded in presenting the study of molecular architecture as an even more appealing discipline. Moore graduated from Vanderbilt (B.A. 1935, summa cum laude ) with a major in chemistry. The faculty recommended him for a Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation Fellowship which took him to the University of Wisconsin where he received his Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 1938.

His thesis research was in biochemistry in the laboratory of Karl Paul Link. The first lessons that the young graduate student received from the skilled hands of his professor were in the microanalytical methods of Pregl for the determination of C, H, and N; Link had recently returned from Europe where he had studied in the laboratory of Fritz Pregl in Graz. This training from Link in microchemistry was especially valuable for a student who was later to be concerned with the quantitative analysis of proteins. Moore’s thesis was on the characterization of carbohydrates as benzimidazole derivatives. The experience of bringing that work from the bench to the printed page under Link’s guidance marked Moore’s transition from a student to a productive scholar.

Karl Paul Link was a friend of Max Bergmann, who had recently arrived from Germany to lead a laboratory at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York. Through that friendship, Moore was encouraged to join the Bergmann Laboratory in 1939, which was an internationally renowned center of research on the chemistry of proteins and enzymes. During Emil Fischer’s last years Max Bergmann had been his senior research associate, and Bergmann had attracted to Rockefeller a group of versatile chemists who maintained a tradition of innovative research and high productivity. After nearly three valuable years in such company, which included William H. Stein, the advent of World War II drew Moore out of the laboratory to serve as a junior administrative officer in Washington for academic and industrial chemical projects administered by the Office of Scientific Research Development. At the close of the war, he was on duty with the Operational Research Section attached to the Headquarters of the United States Armed Forces in the Pacific Ocean Area, Hawaii.

During the war years, the situation at the Rockefeller Institute had changed. The untimely death of Max Bergmann in 1944 had brought to a close the major chapter in biochemistry which the contributions of his laboratory comprised. Moore’s decision to return to Rockefeller was influenced by Herbert Gasser, then the Director of The Rockefeller Institute, who offered to give modest space to Moore and Stein to pursue the theme of research which they had begun with Bergmann or any new lines of investigation that appealed to them. Thus began the collaboration that led to the development of quantitative chromatographic methods for amino acid analysis, their automation, and the utilization of such techniques, in cooperation with younger associates, in the researches in protein chemistry summarized in the Nobel Lecture by Moore and Stein.

The investigations were conducted in an atmosphere at Rockefeller that encouraged interdepartmental cooperation and international consultation that would expedite research. Interludes included Moore’s tenure of the Francqui Chair at the University of Brussels in 1950, where, at the generous invitation of E.J. Bigwood, a laboratory of amino acid analysis was organized in the School of Medicine. Moore had the opportunity to round out the year in Europe with six months in England at the University of Cambridge where he shared part of a laboratory with Frederick Sanger during the time of the pioneering studies on insulin. In 1968, Moore was a Visiting Professor of Health Sciences at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Memberships and Activities

American Society of Biological Chemists (Treasurer, 1956-59; Editorial Board, 1950-60; President, 1966), American Chemical Society, hon. member Belgian Biochemical Society, foreign correspondent Belgian Royal Academy of Medicine, Biochemical Society (Great Britain), U.S. National Academy of Sciences (Chairman, Section of Biochemistry, 1970), American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Harvey Society, Chairman of Panel on Proteins of the Committee on Growth of the National Research Council (1947-49), Secretary of the Commission on Proteins of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1953-57), Chairman of the Organizing Committee for the Sixth International Congress of Biochemistry (1964), President of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (1970).

Honors

Docteur honoris causa from the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Brussels (1954) and from the University of Paris (1964). Award shared with William H. Stein: American Chemical Society Award in Chromatography and Electrophoresis, 1964; Richards Medal of the American Chemical Society, 1972; Linderstrom-Lang Medal, Copenhagen, 1972.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Stanford Moore died on August 23, 1982.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.