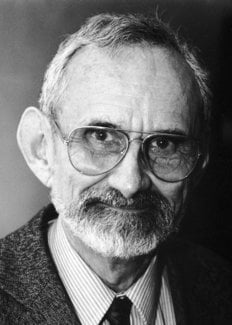

Robert F. Curl Jr.

Biographical

I was born in Alice, Texas on August 23, 1933. My father was a Methodist minister, and my mother was what we then called a housewife. I have a sister, Mary, who is some years my elder. In those days, Methodist ministers moved often, and as a child I lived in a succession of mostly small towns in south Texas: Alice, Brady, San Antonio, Kingsville, Del Rio, Brownsville, McAllen, Austin, then back to San Antonio. During this time the church hierarchy recognized that my father was an able administrator capable of organizing people to get things done and gifted at resolving conflicts. From the time I was about nine my father was no longer pastor of a church but rather a supervisor of church activities over a district. This was a great relief to me as I was spared being the center of judgmental attention as the “preacher’s kid.”

By the time I reached adulthood my father was universally revered as a fair, kind, and gentle man with an acute mind. His most enduring monument will be the San Antonio Medical Center as he worked hard and effectively to start the Methodist Hospital there, which really started the center.

When I was nine years old, my parents gave me a chemistry set. Within a week, I had decided to become a chemist and never wavered from that choice. As I grew my interest in chemistry grew more intense, if not more sophisticated. Of course there was no chemistry in the school program until high school.

I was not a particularly distinguished student as a child. My grades were good but obtained more by steady work than any brilliance on my part. I vividly remember my father telling me that one of my elementary school teachers had told him that I was not brilliant but I was a steady hard worker. Somehow the further I progressed in school, the easier it became to do well.

It was a great delight when I finally got to study chemistry in high school. My teacher, Mrs. Lorena Davis, saw that I was keenly interested and did her best to foster and nourish that interest. As only one year of chemistry was offered then, I had no formal course in the subject to take my final year in high school. Mrs. Davis offered me special projects to satisfy my appetite for chemistry. I remember most constructing a Cottrell Precipitator. I was shocked to see Mrs. Davis, who didn’t smoke, light up a cigarette and blow smoke into the precipitator to demonstrate that it worked.

When it came time to choose a college, I got interested in Rice Institute. It had an excellent reputation as being a good school for a dedicated student. I was also impressed by how well its football team was doing. My parents loved my choice because at that time Rice charged no tuition, and they would have been hard pressed to send me to a university that did. While my father held the highest administrative office, not counting the Bishop, in the Southwest Texas Conference, he did not make much money.

At that time there was a high failure rate at Rice. With no tuition, students were expected to prove themselves worthy or make way for someone else. However, I was ready for the challenge that Rice presented and prospered academically. Socially, my fellow students were ready for the challenge that I presented and worked hard to convert a rather straight-laced, serious boy into someone they could stand to be around.

By a quirk of fate, the most colorful professors I encountered in my first years taught subjects other than chemistry. I liked my first and second year chemistry professors (in fact I later developed a closer relation with my second year professor, John T. Smith), but they were not particularly colorful. It was not until my third year when I had John E. Kilpatrick for Physical Chemistry and George Holmes Richter for Organic Chemistry that the chemistry department began to pull ahead in the colorfulness race. John Kilpatrick came to class, sat in the middle of the table in front, lit a cigarette, took an enormous drag, and began to speak. No smoke came out! Richter enlivened his lectures by describing the pharmacological effects of various organic chemicals. Richter was a fine teacher of Organic Chemistry, but that was of little use to me since I had an almost unnatural aversion to Organic Chemistry. Kilpatrick was the most welcoming to students of any person I ever encountered with absolutely no regard for the amount of time he spent with a student. This, happily for him, made the time he devoted self-limiting, because I would think about whether I had an hour or two to spare before dropping by to see him.

The most impressive chemistry teacher I had was Richard Turner, whom I first encountered in a senior Natural Products course. (The curriculum was cleverly constructed so that it was impossible to avoid a second encounter with Organic Chemistry.) It was his enthusiastic discussion of barriers to internal rotation and the pioneering work of Kenneth Pitzer in the area that made me resolve to go to University of California, Berkeley, and work with Pitzer. This is a decision I have never regretted.

While I was at Berkeley, Pitzer was the Dean of the College of Chemistry and a very busy man. Nevertheless he was always completely accessible to his graduate students, and always genuinely delighted to see me when I interrupted his work. When our conversation reached its conclusion, he graciously got me out of his office. I was grateful for this as well because at the time, as you can see from my comments about visiting John Kilpatrick, I had trouble with leave-takings. I think that I received an excellent education in how to do research from Pitzer. The most important work I did at Berkeley was on Pitzer’s extension of the Theory of Corresponding States. Over the years, I have remained in contact with Ken and Jean Pitzer. Indeed, we were able to collaborate again in research some years later when he was president of Rice University.

My years at Berkeley were some of the happiest of my life primarily because it was during this time that I met and married my wife, Jonel. Our union seemed pre-ordained when we discovered that our ancestors came from the tiny town of Center Point, Texas (pop. 300).

At that time, there seemed to be an unwritten rule that Pitzer’s students should do experiment as well as theory. This suited me, because I had always been interested in experiments. Pitzer suggested that I investigate the matrix isolation infrared spectrum of disiloxane in order to establish whether the SiO-Si bond was linear or bent. If I had tried to do these experiments involving liquid hydrogen without help, I believe there is a good chance an explosion would have resulted. However, a fellow student, Dolphus Milligan, helped me tremendously with these experiments and with his aid I was able to collect the necessary data, which indicated that Si-O-Si is somewhat bent from linearty.

Pitzer was able to help me get a post-doctoral position with E. Bright Wilson at Harvard. At that time, Wilson had developed a method for measuring barriers to internal rotation using microwave spectroscopy and I was still interested in internal rotation barriers. It seemed a perfect situation. I enjoyed Harvard scientifically. Wilson’s personality was very different from Pitzer’s. Although he was born in Tennessee, he personified the New England virtues of upright integrity and serious concern about all aspects of life. His disapproval of superstition in all forms was well-known; none of us would dare mention in his presence the gremlins we all suspected inhabited his microwave spectrometer. Wilson above all was a fine, decent, caring person who wanted the best for his students.

The atmosphere in Mallinkrodt Laboratory at Harvard was somewhat different from that of Lewis Hall at Berkeley. Perhaps it was because the graduate system and expectations for graduate students were different. At that time, a student was expected to complete his Ph.D. at Berkeley in three years while at Harvard it took many students five or even more years. Compared with the laid-back Berkeley graduate students of my day, Harvard students seemed intense and often eccentric. The big exception was Dudley Herschbach, who was modest, relaxed, and friendly, and the most brilliant intellect I had encountered in someone my own age.

In those days faculty hiring was done with few formalities. Somewhat out-of- the-blue, I got an offer to come back to Rice as an Assistant Professor. The prospect of returning to a warm climate and familiar surroundings full of many happy memories was delightful and with no negotiations I happily accepted.

I inherited George Bird’s graduate students and his microwave spectrometer, which was more sensitive than Wilson’s. Of these two strokes of good luck, Bird’s students proved the greater treasure. My very first student was Jim Kinsey. He accomplished so much in the first year that I was at Rice that he graduated. The work we did together on the microwave spectrum of ClO2 and the treatment of fine and hyperfine structure set me up for a productive period of studying the spectra of stable free radicals.

I have remained at Rice from 1958 until today. In my professional and research career, I have played a variety of roles and worked in several areas of Physical Chemistry, too varied to describe further. A great deal of my research has been collaborative involving other principals both at Rice and elsewhere. I have enjoyed quite a few very pleasant research associations over the years. Outside Rice I have collaborated with C.A. Coulson, Roger Kewley, Takeshi Oka, Ken Evenson, John Brown, Eizi Hirota, Shuji Saito, Anthony Merer, Wolfgang Urban, Harry Kroto and Leon Phillips. Among the Rice Faculty, I have enjoyed collaborations with John Kilpatrick, Frank Tittel (for the last 25 years), Phil Brooks, Rick Smalley, Graham Glass and Bruce Weisman. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Rick Smalley, Harry Kroto, and myself for the fruits of one of these collaborations, the discovery of the fullerenes.

I must point out that we do not claim this discovery is ours alone. James Heath and Sean O’Brien, who were graduate students at the time, have equal claim to this discovery. Both Jim and Sean were equal participants in the scientific discussions that directed the course of this work and actually did most of the experiments. The early experiments that Sean and Jim did not do were carried out by Yuan Liu and Qing-Ling Zhang. At an early stage, Frank Tittel became involved in this work. At a later stage, F.D. Weiss and J.L. Elkind did the shrink wrap experiments, which were among the strongest evidence for the fullerene hypothesis.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Robert F. Curl Jr. died on 3 July 2022.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.