Ei-ichi Negishi

Biographical

I was born on July 14, 1935 in Changchun, China, as a Japanese citizen. My family moved to Harbin when I was one and then to Seoul, Korea, two years before the end of World War II. As I was admitted to an elementary school in Harbin at age six, a year earlier than normal, I then came to Seoul as an eight-year old third grader. Shortly after the end of World War II in 1945, my family returned to Japan and moved into a house in Tokyo which my parents had purchased several years earlier that miraculously survived many intensive bombings. A much more serious problem for my parents was how to feed a rapidly growing family of seven, with five children ranging from twelve to one. Their solution to this food shortage problem was to move to an underdeveloped patch of land of a little less than one acre about 50 km southwest of the center of Tokyo. Although my father’s attempt to become a farmer there was not very successful, this naturally wooded area called “Rinkan” in Yamato, Kanagawa prefecture, became what I consider even now my “first hometown,” where I spent my junior high school (seventh-ninth grades), high school (tenth-twelfth grades), and college years (1953–1958 for five years as I needed to repeat my junior year due to gastrointestinal illness).

I was born on July 14, 1935 in Changchun, China, as a Japanese citizen. My family moved to Harbin when I was one and then to Seoul, Korea, two years before the end of World War II. As I was admitted to an elementary school in Harbin at age six, a year earlier than normal, I then came to Seoul as an eight-year old third grader. Shortly after the end of World War II in 1945, my family returned to Japan and moved into a house in Tokyo which my parents had purchased several years earlier that miraculously survived many intensive bombings. A much more serious problem for my parents was how to feed a rapidly growing family of seven, with five children ranging from twelve to one. Their solution to this food shortage problem was to move to an underdeveloped patch of land of a little less than one acre about 50 km southwest of the center of Tokyo. Although my father’s attempt to become a farmer there was not very successful, this naturally wooded area called “Rinkan” in Yamato, Kanagawa prefecture, became what I consider even now my “first hometown,” where I spent my junior high school (seventh-ninth grades), high school (tenth-twelfth grades), and college years (1953–1958 for five years as I needed to repeat my junior year due to gastrointestinal illness).

Figure 1. Early Family Photos. Top: The Suzuki Family (ca. 1950): Back row: Tsuguo Suzuki (father), Sumire, Misao (mother) and Kenji; front row: Akemi, Yutaka and Yuzuru. Bottom: The Negishi Family (1958): Back row: Sumire, Masako, Fusae (mother), Shizuko, Chieko, and Noriko; front row: Akiko and Ei-ichi.

Figure 1. Early Family Photos. Top: The Suzuki Family (ca. 1950): Back row: Tsuguo Suzuki (father), Sumire, Misao (mother) and Kenji; front row: Akemi, Yutaka and Yuzuru. Bottom: The Negishi Family (1958): Back row: Sumire, Masako, Fusae (mother), Shizuko, Chieko, and Noriko; front row: Akiko and Ei-ichi.

Despite all these difficulties, I recall my early school years through ninth grade mostly with positive and enjoyable memories. Although I virtually never studied outside classrooms through the ninth grade, I was quite alert and enjoyed most of the classes with the exception of calligraphy and Japanese language. But, I enjoyed after-school hours before darkness even more. Those short after-school hours in the nearly six-month-long Harbin winters were spent skating in the playground covered with ice. I hardly recall my indoor activities before darkness through ninth grade. Several classmates and I in our junior high school jointly collected naturally growing grasses for rabbits and took care of chickens, which virtually every family in our area was raising for food and minor supplementary income, but we never forgot to set aside some time for playing ball games and so on. For some reason, I found a world atlas in our very modest bookshelf to be to my liking and almost daily looked at it in the evening, especially during my Harbin days. I luckily established myself as one of the top students throughout my elementary and junior high school years.

My first setback, if only a temporary one hit me, when I applied for an “elite” high school in our prefecture called Shonan High School. Despite my superior scholastic standing, I was declared ineligible, because I was a year younger than my classmates. Luckily, several of my teachers at Yamato Junior High School including my classroom teacher, S. Koyama, and music class teacher, T. Suzuki, who was the father of my future wife, Sumire, successfully persuaded Shonan High School officials to accept me. At Shonan, which only the top several of my two hundred plus classmates at Yamato Junior High School attended, my life style described above was no longer satisfactory. Nor was I sufficiently ambitious about my higher education. I soon noticed that the entire school was obsessed with the single notion of intensely training and successfully sending as many students as possible to several of the most highly rated universities, represented by the University of Tokyo, several other former Imperial Universities such as Kyoto, Osaka, and Nagoya, as well as the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Throughout my first year at Shonan, I was still mostly limiting my studying to that in the classrooms, which led me to earn the 123rd place in scholastic standing among a little more than 400 classmates. After a brief moment of disappointment, I then realized that, whereas there were a little more than 100 students who were ahead of myself, there were also nearly 300 others behind me. Back in those days, about 30–40 students including one-time repeaters were successfully entering the University of Tokyo each year from Shonan. It then suddenly occurred to me that, if I studied as hard as I could, even I might have a legitimate chance of entering the University of Tokyo, which until then appeared far beyond my reach.

For the first time in my life, I instantly became a self-motivated and highly disciplined model student devoting most of my available time to intensive studying. I would wake up a couple of hours earlier than the rest and spend those extra hours in preparation for classes each day. No more solitary explorations of my favorite Shonan seaside area, especially Enoshima Island, after classes. Each evening, I would study until after 11 pm when I heard my mother’s gentle reminder saying: “Isn’t it about time to stop studying and go to bed?” In retrospect, I feel very fortunate that neither of my parents ever told me to study more or harder in my life. For one thing, they themselves were very busy just for our survival, even though I did amply sense their silent but strong mental support for my higher education.

At the end of the first semester of 11th grade, my scholastic ranking rose to the 9th among a little more than 400 students. I then reached the top position at the end of the 11th grade and maintained that position through the 12th grade. Toward the end of the 11th grade and through most of the 12th grade, a series of several mock college entrance examinations were given, and I managed to earn the highest overall scores three out of five times. Naturally, my confidence grew sharply. At the same time, however, I began feeling an intense psychological pressure against never failing in the upcoming real entrance examinations as the top student at Shonan. Indeed, this mental pressure was most intense during the two-day entrance examinations for the University of Tokyo and both my mental and physical conditions were at the worst, short of being outright sick. I really thought my performance on those two days was at its worst, and I felt more than halfway certain that I failed. Fortunately, I did pass, perhaps barely, and became one of the youngest college entrants at age 17 in the stiflingly rigid Japanese system. Fortunately, there was no age-based opposition this time.

In retrospect, I now consider the oft-criticized rigorous college entrance examination system in Japan to be a highly valuable and effective training of teenagers in preparation for their research and other professional careers, especially in science and engineering areas. Even today, 55–60 years later, I very frequently resort to my mathematical and scientific background, which I quite firmly built in my high school days in preparation for the college entrance examinations.

Having accomplished my high school goal, my eccentric and erratic lifestyle took another 180-degree turn. Even though my major in college was non-biological science and engineering, our curriculum for the first two years at the Komaba campus, designated as General Education, was full of non-scientific classes including a second foreign language − German for myself − law, economy, psychology, and so on, along with a limited number of mathematics and natural science classes. With some exceptions, neither students who had just survived very demanding college entrance examination, nor professors, who probably were mostly interested in and preoccupied with pursing their own professional interests, appeared to be sufficiently interested in learning or teaching the subject matter. For example, there were two different German classes in my curriculum. Most of the students in these classes were taking German lessons for the first time in their lives. One class dealt strictly with German grammar. In the other class, we were asked to deal from the very beginning with German novels and poems. I recall our trying to read and interpret Goethe’s poems, while consulting a German-Japanese dictionary for almost every word with little grammatical knowledge. This was clearly a very poor way of learning any foreign language. Coupled with a serious lack of effort on my part, my knowledge and ability in German are even today very limited and poor. Nearly the same can be said about most of the other subjects as well .

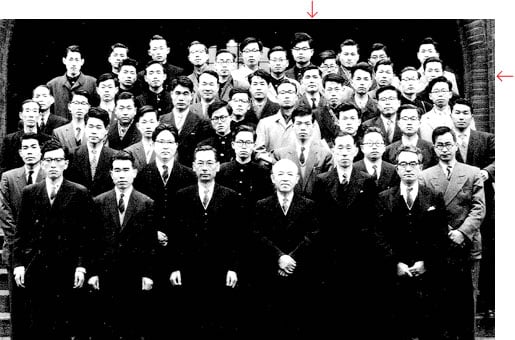

Figure 2. Classmates at University of Tokyo (1958). E. Negishi indicated with arrows.

In the meantime, I quickly diverted my time, interest, and efforts to some off-campus activities, such as (1) listening to Western classical music, especially Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Dvorak, Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and so on, (2) singing in and conducting a small choir group mostly performed at the small house of my music teacher at Yamato Junior High School, Tsuguo Suzuki, who later became my father-in-law. Kenji Suzuki, Tsuguo’s eldest son and one of my classmates at Shonan High School and also at the University of Tokyo, was the other leader of the small choir group. To my disappointment, Sumire, the older of two daughters of Tsuguo Suzuki and my future wife, would stay away from our choir activities, even though she was undoubtedly forced to listen to the sounds we generated in the small house. For one thing, she was younger by three years than most of the choir group members (two years younger than myself), and she probably felt she did not belong to our choir group. Even so, Sumire and I started dating during my freshman year, and we rapidly got closer with time.

As I spent much of my available time in these extra-curricular activities, I all but forgot my self-motivated studying. Even today, I occasionally regret my lack of continued efforts, which I acquired during the latter half of my time at Shonan High School. Clearly, I was primarily responsible for this academically non-productive two-year period at the Komaba campus of the University of Tokyo, but I also believe that there was considerable room for improvement in many areas of curriculum development.

Despite my failure to make due efforts, I was surprised with much relief when I learned that my scholastic ranking at the end of the first year was barely in the top third among ca. 450 non-biological science and engineering majors. This permitted me to choose one of the most highly coveted departments at that time, applied chemistry specializing Industrial Chemistry, for my Junior and Senior years. In and around 1955, ten years after the end of World War II, the Japanese economy was growing rapidly − in part because of the unfortunate Korean War near Japan. In particular, the newly rising non-natural polymer industry was booming and attracting young scientists and engineers such as myself to join this field.

Despite all these promising developments, I experienced probably the hardest and least productive time in my life. First of all, it required almost two hours one way or four hours both ways to commute between my home in Yamato and the Hongo campus of the University of Tokyo. Our class schedule in my junior year was packed with a series of lecture and laboratory classes full of superficial discussions and experiments on various industrial chemical processes from 8 am to about 5 pm every day. Only in a relatively small number of classes did we learn some fundamentally important chemistry. Unfortunately, however, most of these classes were, in my opinion, rather poorly taught. In a class on quantum chemistry, for example, a widely known textbook (the Japanese version) entitled “Valence” by Coulson was chosen, but virtually no penetrating and nourishing discussions were presented in class. In fact, I needed to wait for four more years until I took a class on this same subject with the same textbook (the original English version) at the University of Pennsylvania, which finally permitted me to acquire the important quantum chemical background at an adequate and useful level.

Between physically demanding commuting − which required almost four hours of standing in jam-packed commuter trains − and highly time-consuming but seemingly non-nourishing lecture and laboratory classes, I began suffering from gastrointestinal problems by July of 1955. The problems got worse during the latter half of that summer break, and I was finally hospitalized for a few weeks, which prevented me from taking all of the mid-year tests. Eventually, I was forced to repeat my junior year.

In retrospect, this major setback proved to be a blessing in disguise. For one thing, I had plenty of my own time to think, plan and do some new things for myself according to my own plans. I read almost indiscriminatingly a wide range of books ranging from the Bible, although I was not a Christian, to “how to …” publications. Through all these reading and thinking activities, I reached my own notion that “happiness” must be the ultimate goal for each of us and that the following are the four essential components of it: (1) good health, (2) happy surroundings including one’s own family and beyond, (3) selection and pursuit of a worthy professional career, and (4) one or more enjoyable and lasting hobbies.

With my renewed life goals, I restarted my junior year in April, 1956. This time, I decided to rent a small room across from the Hongo campus, but I would go home almost every weekend from Friday evening to Sunday evening. Another new item I added to my plans was learning conversational English, which I considered to be critically important for my career development. Throughout my junior and senior years, however, I remained critical about the combination of mostly superficial descriptions of various chemical processes and a smaller number of fundamentally important subjects that were, in my opinion, rather poorly discussed in classrooms. Clearly, I was also responsible for my inability to make better use of these classes. My music-related activities were maintained and exercised over the weekends, and I began steadily dating with Sumire with a growing notion of our eventually getting married.

During the latter half of my junior year, I applied for a lucrative scholar ship from one of the leading synthetic polymer companies, Teijin, Ltd. and successfully obtained it with the agreement that I would join Teijin upon graduation. This virtually eliminated my concerns over various financial matters including the costs of dating with Sumire. I regret very much that amid all of these activities, my efforts in my Senior Research project based mostly on experimental work were kept minimal.

On the day of graduation with the degree of Bachelor of Engineering in March, 1958, Sumire and I announced our engagement to our parents in a small restaurant near Akamon (“Red Gate”) of the Hongo campus.

At Teijin, I was assigned to be a research chemist at the Iwakuni Research Laboratories, then the main research facility of Teijin, which was located near Hiroshima in the Inland Sea area. One of my superiors there asked me to systematically explore chemical reactions of polymers to come up with modified polymers of superior properties. It soon was apparent to me that my synthetic organic chemical background was woefully weak. I immediately told myself, “I should rebuild almost from scratch my synthetic organic chemical background,” something I already had been vaguely hoping to do independently of this episode. The most obvious thing to do was to return to the University of Tokyo as a graduate student pursuing a master’s degree. The main difficulty was how to raise the tuition fees, as virtually no graduate teaching assistantships were available back then in Japan. I recall the welcome speech by the President of Teijin, Mr. S. Ohya, in which he strongly urged all new members of the company to study and master some foreign languages, especially English, German, and French. He also told us about the Fulbright-Smith-Mund All-Expense Scholarship permitting highly qualified recipients to study in the U.S. for up to three years, and he further indicated that, if anyone at Teijin won this scholarship, Teijin would grant a leave of absence with some additional financial support. As indicated earlier, I had been studying conversational English on my own for about three years. So, I decided to pursue the recommended course of events. In fact, the Teijin Iwakuni Research Laboratories soon hired a native English-speaking foreign tutor and I started taking an English conversation class, which proved to be a most useful experience for me to acquire a solid foundation of conversational English. Once again, my self-motivated diligent study habits came back, and I quickly became quite proficient in practical English.

The two-stage Fulbright Examination on written and conversational English was by far the most competitive examination up to that point in my life, but I was luckily chosen as one of the only two who passed out of a little more than 150 applicants. Looking back, I consider my winning a Fulbright Smith-Mund All-Expense Scholarship to come to the U.S. in 1960 and study toward my Ph.D. degree in Synthetic Organic Chemistry to be the single most important turning point in my professional career.

The Fulbright Commission asked me to list three universities. The final one would be selected through negotiations by the Fulbright Commission with the listed universities. With almost zero knowledge about American universities, I consulted the Journal of Polymer Science, which I was most frequently reading, and noted the names of three editorial board members who were at Princeton University (A.V. Tobolsky), the University of Pennsylvania (C.C. Price), and the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute (C.G. Overberger). The Fulbright Commission chose University of Pennsylvania for me.

After 8 weeks of English orientation classes at the University of Hawaii in August and September, 1960, I came to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. I spent three years there for my Ph.D. degree, which I obtained in December, 1963 under the guidance of Professor A.R. Day.

Before 1960 Japan had produced just one Nobel Laureate, H. Yukawa, who won a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1949 only four years after the end of World War II. Although I vaguely knew of him, he was a physicist in Kyoto, which is some 500 km away from Tokyo. So, he was like a figure in a fairy tale to me. On the other hand, a series of a dozen or more Nobel Laureates in sciences as well as those who had not won but were clearly destined to win Nobel Prizes visited Penn to give lectures during my stay there. On some other occasions, several of us at Penn would get together and drive to other universities within several hours’ driving distance to attend lectures by Nobel Laureates. In this way, I attended easily more than a dozen lectures by Nobel Laureates including G.T. Seaborg, H. Staudinger, L.C. Pauling, M. Calvin, M.F. Perutz, J.C. Kendrew, K. Ziegler, R.B. Woodward, D.H.R. Barton, and H.C. Brown. I even personally talked to them. They were no longer figures in fairy tales.

Figure 3. Ei-ichi Negishi flanked by his former associates and Professors S. Murahashi and M. Anastasia.

Through these opportunities, the Nobel Prize became something of reality to me. I must confess that, in my usually quixotic way, I even began thinking that if I keep trying in the right direction and on the right track, I might even have a remote chance of winning one some day.

As a first-year graduate student at Pennsylvania, I was a reasonable Ph.D. student in class. However, I am much more proud of the fact that I earned 8 consecutive grades of excellence in the Organic Cumulative Examinations, a feat essentially unheard of back then. This indeed gave me a tremendous amount of confidence in myself and in my potential research capability.

Figure 4. Nobel Celebration at Purdue. Top: Negishi display ribbon-cutting in Chemistry Building. Bottom: News conference with Purdue President F. Córdova.

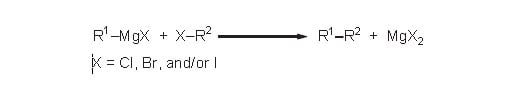

In the laboratories, however, I was at least initially rather clumsy and failed in a fair number of experiments. I then began questioning many aspects of organic synthesis, as it was known then. “Why are so many organic synthetic reactions esoteric?” “Why are so many of them including acetoacetic ester and malonic ester syntheses roundabout and yet of limited synthetic scope?” It was around those days that the following dreamy, if childish, notion occurred to me. If we could come up with widely applicable, straightforward LEGO-game like methods for hooking up together two different organic groups, R1 and R2, to produce R1–R2, the entire task of organic synthesis would be vastly simplified and generalized. In fact, the Grignard cross-coupling reaction shown in Eq. 1 had long been known, even though it might have been a relatively unimportant reaction of very narrow synthetic scope within the vast scope of Grignard’s Nobel Prize winning work known about a century ago.

In the Grignard cross-coupling reaction shown in Eq. 1, Mg and halogens are used to promote the desired formation of R1–R2 both kinetically and thermo dynamically. Through such simple but unmistakable considerations, I soon became obsessed with the notion of exploring organometallic chemistry in order to solve a wide range of problems in organic syntheses, which eventually led me to join H.C. Brown’s group as a Postdoctoral Associate for two years (1966–1968) and then as his Assistant with the rank of Instructor for four more years (1968–1972). During the latter four-year period, I was given a considerable amount of freedom to pursue my own ideas and plans. Indeed, it was during this four-year period that I became interested in the possible uses of d-block transition metals as catalysts for promoting main-group metal-containing organometallic reactions, such as those shown in Eq. 1. In addition to some pioneering works of M.S. Kharasch, which led to the Cu-catalyzed alkylation of Grignard reagents by J. Kochi in 1971 and its Ni-catalyzed version by K. Tamao and M. Kumada as well as by R. Corriu in 1972, some other initially stoichiometric reactions of organometals containing (i) Cu by H. Gilman, which was extensively further developed by E.J. Corey, (ii) Pd, mostly π-allylpalladiums by J. Tsuji and by B.M. Trost, as well as arylpalladiums by R.F. Heck, and (iii) Ni, mostly π-allylnickels by E.J. Corey, M.F. Semmelhack, and L.S. Hegedus became widely known since the late 1960s.

Figure 5. The Negishi’s, December 2010.

Despite all these mostly stoichiometric reactions of organotransition metals, containing Cu, Ni, Pd, and some others, widely applicable methods for C–C bond formation that are highly catalytic (TON ≥ 103 – 104) in transition metals were virtually unknown at the time I started my independent career as Assistant Professor at Syracuse University in July, 1972. I therefore chose with much enthusiasm “Discovery and Development of New Organic Synthetic Reactions Catalyzed by Transition Metals” as the central topic of my life-long research projects. One important aspect of it is the subject of my Nobel Lecture, presented below.

Ei-ichi Negishi died on 6 June 2021.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.