Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Article

by Stig Fredrikson*

This article was published on 22 February 2006.

How I helped Alexandr Solzhenitsyn smuggle his Nobel Lecture from the USSR

A controversial Nobel Prize

When Alexandr Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970, he was already an outcast in his native country, the Soviet Union. After the novel “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” and a few short stories he had not been permitted to publish anything. He had been expelled from the Writers’ Union, and the harassment from the Communist Party and the KGB, the Committee for State Security, had made him isolated and exposed him to condemnation from the official media.

The Nobel Prize gave his enemies more ammunition. Solzhenitsyn was said to have been rewarded for his “anti-Soviet writings.” He decided not to go to Stockholm in December 1970 to receive the Prize. He feared that he would be deprived of his Soviet citizenship and prevented from coming back if he went to Stockholm. He could not imagine being cut off from Russia where, in secrecy, he was writing several new works. And in Moscow his new wife Natalya was expecting their first child.

For a while there was talk of handing over the Nobel Prize to Solzhenitsyn at the Swedish Embassy in Moscow. However, the conditions that the Swedish ambassador, Gunnar Jarring, and the Swedish government under Olof Palme put up were unacceptable to Solzhenitsyn. The Swedes proposed a private transaction. They excluded a public ceremony open to all the friends and other guests that Solzhenitsyn wanted to invite and a public lecture by Solzhenitsyn. The Laureate answered that the conditions were “an insult to the Nobel Prize itself” and wondered if the Prize was “something to be ashamed of, something to be concealed from the people.” This experience left Solzhenitsyn with a deep sense of humiliation, both from the condescending way he was received when he twice visited the embassy to seek advice, and by the cowardly way a prize ceremony at the embassy was to be handled.

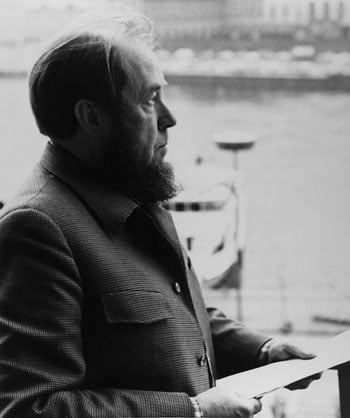

A Laureate’s profile. Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, December 1974, in Stockholm to receive his Nobel Prize.

A foreign correspondent in Moscow

I came to Moscow in early 1972 to work as a correspondent for TT, the Swedish News Agency, and the news agencies in Finland, Denmark and Norway. With my wife Ingrid I moved into an apartment in the foreigners’ compound at Kutuzovsky Prospect where one room was used as my office. I had learned Russian at the Swedish Army Language School.

Soon after my arrival I was informed from Stockholm that the Swedish Academy planned to arrange a ceremony in Moscow. The permanent secretary, Karl Ragnar Gierow, was to hand over the Prize to Solzhenitsyn in his new wife’s apartment. The information came from my editor at TT, Hans Björkegren, who was also Solzhenitsyn’s Swedish translator. It was therefore natural for the Academy to turn to Björkegren with a question about the Solzhenitsyn family’s practical arrangements for the ceremony. Björkegren passed the question – and Solzhenitsyn’s then secret address – on to me. I went to Natalyas’s apartment – Solzhenitsyn himself had been denied permission to register as a resident in Moscow – on Gorky Street and met her and her husband Alexandr Isayevich. I then transmitted in innocent words the message to Stockholm.

The Prize Ceremony was planned for April 9, 1972, the Russian Orthodox Easter Sunday. But Karl Ragnar Gierow was refused a visa to go to Moscow, and Solzhenitsyn had to cancel the ceremony. In an angry letter that he released to the press Solzhenitsyn asked the Swedish Academy to “keep the Nobel insignia for an indefinite period.”

“If I do not live long enough myself, I bequeath the task of receiving them to my son,” he said. But he was still determined to deliver his Nobel Lecture to Stockholm.

A Nobel Lecture happily arrives in Stockholm

During our meeting at Natalya’s apartment Solzhenitsyn and I had arranged to try to meet once again, in the underground passage at the Belorussian railway station. In the enlarged version of his literary memoir “The Oak and the Calf”, which was published in Moscow in 1996, Solzhenitsyn describes the meeting:

“I had in my pocket a film containing the text of the Nobel speech. We had failed to find any other way of sending it out, and once again, its destination was Sweden. I was standing in an inconspicuous spot; he and his wife Ingrid came strolling along arm in arm: I followed, keeping a gap between us, and Alya came behind me, after first watching out for a while from a different spot to make sure that no one was tailing us. Everything turned out fine, so we caught up with them and the four of us set off at a leisurely pace down the Leningrad Prospect. As we talked, I asked Stig if he would take the film, and he agreed. I handed it over in a dark courtyard. Folk wisdom has it that seeing a pregnant woman means your plans will come to fruition. Well, we had two of them, both our wives were pregnant.”

That evening in late April 1972 was when my career as a secret courier to Solzhenitsyn started. It was to last for almost two years, until Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported into exile in February 1974. During that time I had some twenty secret meetings with him when he handed over material destined for the West, while I gave him letters sent to him mostly from his lawyer Fritz Heeb in Zürich. On a couple of occasions Ingrid met, in addition, with Natalya. They strolled along a boulevard with their baby carriages, and when they bent down to look at the babies, they also exchanged small packages.

When I came back to the apartment after that first meeting I looked at what Solzhenitsyn had given me. He had photographed the manuscript of his Nobel Lecture; I had received nine black and white negatives wrapped in a paper envelope. I took a small transistor radio, unscrewed the back, took out the batteries, and in the empty space I placed the negatives. I had cut the negatives into strips, wrapped them up in plastic and put the roll in an empty tube of headache tablets. The tin tube fitted nicely in the battery space. I put the radio in my suitcase and took the train to Helsinki for a conference with my editors. Everything went smoothly at the border, and in Helsinki I could tell my editor Hans Björkegren that “I have mail for you from Moscow.”

We decided to continue to Stockholm where we delivered the Nobel Lecture to the Swedish Academy. The lecture was published in the Swedish and international press in August 1972 and printed in the Nobel Foundation’s publication Les Prix Nobel 1971. It was a very powerful text, which caused a sensation when it came out, and was quoted all over the world. It was the first time that Solzhenitsyn mentioned and made known the name “The Gulag Archipelago”, where, as he said, “it was my fate to survive, while others – perhaps with a greater gift and stronger than I – have perished.”

My work as Solzhenitsyn’s secret courier

The successful delivery of the Nobel Lecture encouraged Solzhenitsyn to entrust me with new missions. I took out one or two things more for him personally but soon decided that I would have to find some other way. It was becoming too dangerous! I risked being caught at the border crossing sooner rather than later, and besides, I left Moscow only a couple of times every year. The volume of the “mail” from and to Solzhenitsyn rapidly increased. I turned to the Norwegian Embassy in Moscow. They let me use their diplomatic pouch for Solzhenitsyn’s deliveries, since they considered me, a Swede, to be a Norwegian correspondent, representing the Norwegian news agency. I never bothered to ask the Swedish embassy, they didn’t allow the Swedish correspondents to send even a personal letter out through them. The Norwegians, of course, were fully informed of the contents of the letters and envelopes I delivered to them, as were my editors at the news agencies, who were informed of my secret meetings with Solzhenitsyn.

Solzhenitsyn called this channel the GNR, The Great Northern Route. He described our secret meetings fondly in his memoir:

“Gradually I became aware that these meetings were indispensable to me. I could not live without them. How could I have existed for nine years without any direct personal contact with anyone from the West? It gave me an unprecedented degree of maneuverability and a rapid means of getting materials abroad; each time we met, there was always something that needed sending or something passed on to me. There were little rolls of film, new works, and new variants of existing ones.”

Why did I say yes that April evening when Solzhenitsyn asked me if I could get his Nobel Lecture out? Why did I decide to become his secret courier? I have been pondering these questions many times – but at the time when it happened, I don’t think it took much reflection on my part. I felt that I didn’t have much of a choice. It was exciting that he asked me, and I felt that if I could help him, I wanted to do so. He was so isolated, so persecuted. He was leading a one man struggle against an overwhelming enemy with the enormous resources of the totalitarian state in its determination to silence him. I came from a country where we take our human rights for granted and where, for example, the right to a private correspondence is a natural thing. If I could help him enjoy at least a small part of our privileges, I felt it was my duty to do so. But I don’t deny at all that what drove me on was also a strong sense of adventure. He was the most admired, the most coveted among the dissidents for interviews by the foreign correspondents in Moscow, and for almost two years I had this exclusive access to him. He is also a man with a strong charm and charisma. It is evident throughout his career that he has been able to get friends to help him. He is not a man to whom you say no easily.

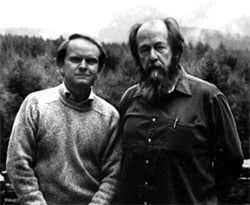

Stig Fredrikson and Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, Easter 1984. By then, the Laureate was in exile in Vermont, USA.

On the other hand, I didn’t agree to become Solzhenitsyn’s secret courier in order to have a good story to tell later. It is important to stress that while this went on, and later, I thought that I would never be able to tell my story. The four and a half years we lived in Moscow did not prepare me at all for what happened in 1991. We experienced a strong monolithic state where the Communist party, the KGB and the military seemed to be able to control Soviet society. I expected the Soviet Union to exist during my lifetime, and therefore, it would be impossible to reveal my secret dealings with Solzhenitsyn. Everybody involved had to be protected. Maybe, I thought after we had moved back to Stockholm, I ought to write down what Ingrid and I had been through, to document it, and put it in a sealed envelope for the future.

By becoming a courier for Solzhenitsyn I also stepped out of my role as a foreign correspondent in Moscow. A journalist is supposed to report about events, not become an actor himself and create events. My solution to this dilemma was to decide that my news agencies should never miss any news story where Solzhenitsyn was involved. But I decided, in agreement with Stockholm, that I would never have any first exclusive news about him. In practice this meant that when I met Solzhenitsyn and he gave me a new statement protesting this or that in the Soviet state, I gave it first to one of my colleagues, usually a news agency like the AP or Reuters. They would give out a “flash” news telegram, TT would also give out a short version in Swedish, but they knew that I would deliver a longer version of the story an hour or so later. In this way, my agencies would also get the Solzhenitsyn news from their own correspondent in Moscow, but not the very first short version. To have “an exclusive” with Solzhenitsyn was too dangerous; it would reveal me as the direct source of statements from Solzhenitsyn, and it would have jeopardized the future of the “GNR”. Not to have a scoop involving Solzhenitsyn was the price I decided to pay to be able to continue as “Alexandr’s courier”.

How we fooled the KGB

Why were we never caught? I have no convincing answer. We were up against the most formidable opponent. I always thought that if there was one single Soviet citizen that the KGB should keep absolute control over, that would be Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. During those years he was probably considered “the Soviet Union’s enemy number one.” I knew that Solzhenitsyn took elaborate precautions when he had a meeting with me in the evening. He would board a commuter train from the village outside Moscow where he stayed in the garage at Mstislav Rostropovich’s dacha. He would get off the train, hop on to another and later switch to the Metro where he could ride for hours, changing trains and platforms until he had convinced himself that no one followed him. I would leave our apartment in the foreigners’ compound either in my car or by foot and walk around for an hour or two before meeting him. And I suppose it helped that I never publicly associated myself with Solzhenitsyn in my reporting. But still, in view of the enormous resources that the KGB had at its disposal for surveillance, how could we go unnoticed? Much later, in 1993 when Alexandr Isayevich agreed to a first long interview for Swedish Television, I asked him: “Why did we get away with it?”

His answer was that “even in the most perfect organization there are bunglers. They missed us. Besides, we were cunning.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and after the archives had been opened, I tried to find out how much, if anything, the KGB had known about us. I asked Vadim Bakatin who became head of the KGB after the coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. Bakatin told me that Gorbachev had asked him, probably in the autumn of 1991, to find out what the KGB archives contained about the persecution against Solzhenitsyn. After an internal search Bakatin came back with the sad news that nothing had been found. Bakatin had discovered a decision from July 1990 ordering all materials about Solzhenitsyn to be destroyed. 105 volumes about Solzhenitsyn in the KGB archives, enough to fill a small truck, were burned, Bakatin told me. His explanation was that the KGB leadership in the summer of 1990 saw the democratization and reforms moving towards them with great speed and decided to wipe out all traces of the harassment of the Soviet Union’s best known critic. Nobody was going to be held responsible.

The story of my secret meetings with Solzhenitsyn has ingredients of a spy thriller. We had to act like secret agents. But in contrast to the novels, everything was true. Nothing was ever written down between us, all the arrangements about time and place for the meetings were kept in our heads. We had alternate dates, and reserve dates for the alternates, if something made it impossible for one of us to show up. I had also thought of the possibility that he might need an urgent meeting with me; normally there were a few weeks between our meetings. I proposed that he call me on my telephone in the office early in the morning before my Soviet secretary arrived at nine. But wasn’t the telephone tapped? Yes, but I told Solzhenitsyn to pretend to make a wrong call. Call my number and ask: “Hello, is this the dry-cleaner’s?” or “Is this the home delivery service of the Gastronom?” People made wrong calls in Moscow all the time, it happened almost daily, and when it happened you just said “you’ve got the wrong number” and slammed the receiver down. If Solzhenitsyn made a wrong call to me, the KGB might not react. But I would immediately recognize his voice, even he only asked for the dry-cleaner’s, and it would be the signal. It meant that something has happened and we had to meet at once.

The publication of “The Gulag Archipelago”

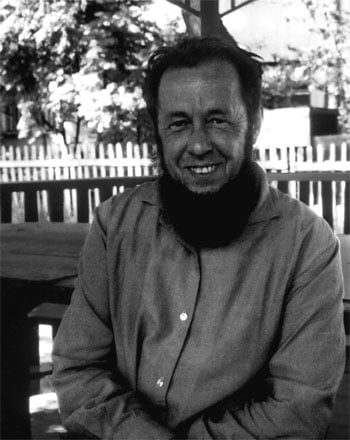

The call came one morning in early September 1973. By then we had switched from the Belorussian station to the Kiev railway station and the streets around it, and we had also met a couple of times in the morning, in broad daylight. This had given me a chance to take some pictures of Solzhenitsyn, for the first time. But after the alarm call, we met that evening.

Solzhenitsyn told me then that the KGB had gotten hold of a copy of the manuscript of “The Gulag Archipelago”. He had written it in secret and he had seen to it that copies of the manuscript were already in the West. People were busy translating it to English, French and German, but Solzhenitsyn had planned to wait to have it published. He had also hidden copies of the manuscript with trusted friends in the Soviet Union. A woman in Leningrad, had one copy. She had buried it in the ground, but somehow the KGB found out. They interrogated her for days and nights until she confessed where she had hidden it. She was then released but went home and hanged herself. She felt that she had betrayed Solzhenitsyn’s confidence in her.

A quick study of the Laureate by the author during one of their secret meetings at the Kiev railway station, June 1973.

Now Solzhenitsyn feared that the KGB would use the manuscript to somehow discredit him. He decided to act before them. He gave me a letter with an order to speed up the translations and have the first volume of “The Gulag Archipelago” published in several countries in the West as soon as possible, and in Paris also in Russian. He also gave me a press release, a small typewritten statement, where he revealed the existence of the till then unknown book, “a documentary study in several volumes about the Soviet prison camps in the years 1918-1956, based on evidence from more than 200 people who on different occasions spent time in the camps.”

“The Gulag Archipelago” started coming out in late 1973, also in Sweden. Hans Björkegren was one of the translators that had had early access to the manuscript. It became a sensation all over the world, and Solzhenitsyn forever changed the way not least intellectuals in Western Europe looked at the Soviet Union. What was most damaging was that he proved that the labor camps were a result of a decision by Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union, and not a deviation perpetrated by Stalin.

After a few weeks of international reporting negative to the Soviet Union, the authorities decided to act. My last secret meeting with Solzhenitsyn was on January 14, 1974. That day Pravda, the party newspaper, had printed a furious attack on Solzhenitsyn and called him “a traitor”. Solzhenitsyn impressed me with his calm and balance, although he was in the eye of a hurricane. “He was so cheerful, he had not read Pravda today,” I wrote later. “How can he be so glad, how can he joke and laugh, show such poise, he was convinced that they had not yet reached a decision at the top” about what to do with him.

But on February 12, 1974, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn was arrested at Natalya’s apartment on Gorky Street. The next day he was deprived of his Soviet citizenship, put on a plane to West Germany and sent into an exile that was to last until the summer of 1994.

He moved back to Russia, after 18 years in Vermont, USA. He has since then been living with his family in a house in a small village, Troitske-Lykovo, a half hours’ drive west of Moscow. On December 10, 1974, he finally received his Nobel insignia at the traditional Prize Award ceremony in Stockholm.

Alexandr Isayevich and I had planned our next meeting for February 14, two days after his arrest. When I now look at my notes I can see that I had planned to give him, among other things, baby food at that meeting. At the time of Solzhenitsyn’s arrest, he and Natalya had three small sons. The family could leave Moscow six weeks later and reunite with Alexandr Isayevich in Zürich.

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and his three sons, 1974, astride a horse that had been turned into stone.

Solzhenitsyn and I have maintained our personal friendship although we soon discovered, after he had been sent into exile, that we had serious political differences of opinion, not least about the West. In September 2004, after I had published my book “Alexandr’s courier”*, I was able to hand him a copy when I visited him in Moscow. He was visibly aged physically, and when I showed him a book of his that I had bought in a Moscow bookstore, he wrote in it:

“Dear Stig, at this, maybe our last, meeting – in unfailing grateful memory.”

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn

* Published in Swedish. “Alexanders kurir: Ett journalistliv i skuggan av det kalla kriget”, Carlsson Bokförlag, Stockholm, 2004.

Stig Fredrikson has been covering and commenting on foreign news for Swedish Television (SVT) for more than 25 years. After his years as a correspondent in Moscow he worked for the national Swedish radio, as a foreign news reporter covering mostly Eastern Europe. In 1979 he became foreign news editor at the “Aktuellt” news programme of SVT, and he has been with them since then. For four years in the 1980s he was a correspondent in Washington, D.C., USA, and from 1993-2001 the editor-in-chief of “Aktuellt”.

Stig Fredrikson was invited to spend a year as a guest professor in journalism at the Göteborg University, Sweden (2001-2002). At present he is also president of the Swedish National Press Club (Publicistklubben), founded in 1874.

First published 22 February 2006

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.