Seamus Heaney

Article

This is not a spade: The poetry of Seamus Heaney

by Ola Larsmo*

This article was published on 20 February 2007.

At the core of Seamus Heaney’s poetry a profound experience is revealed – that a gap exists between the totality of what can be said and the totality of all that can be witnessed, between the limits of languages and the margins of the actual world in which we live. For Heaney ‘poetry’ is a means of measuring this gap – if not bridging it.

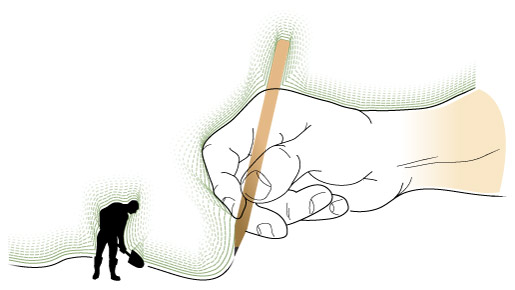

In Heaney’s early poems this gap is connected to a sense of deep loss and even of moral guilt. The young poet keeps encountering a growing distance between the world of language and the physical world he sees around him. In a biographical sense, this may be linked to the fact of being born within an agrarian society where the poet has his roots, but from which the gifts of language and education has excluded him, so that he does not fully belong there any more. This distance is superbly captured in his poem ‘Digging’, from the debut collection Death of a Naturalist (1966).

The young Heaney sits by his desk, pen in hand, and watches his father digging in the garden. As both come from a long line of Ulster farmers, the father is doing what the Heaneys have been doing for generations: tending the land.

by God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

The son does something different:

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

The son has moved into a different world, yet, through his words, both tasks become related. Both dig beneath the surface of things, cultivating the possibilities of what may grow. In this early poem – the first one in his Selected Poems – Heaney uses a rhetoric figure that for a considerable period would be his trademark: the ‘chiasma’, or crossing of themes. The poem starts out with the image of the pen, and goes on to relate what could be termed as the young intellectual’s respect and awe for the seemingly commonplace skills of the working man, represented by his father’s ‘spademanship’ – before the focus returns to the pen, which has now been transformed to a tool for hard work – which Heaney enlists in the genealogical, or historical, line of working men. The pen and the spade trade places and within the course of the poem, quite literally, became metaphors for each other. Spade-as-pen; pen-as-spade.

This ‘crossing of themes’ is a method that Heaney uses repeatedly. In one of the more quoted of his ‘Glanmore Sonnets’ from the collection Field Work (1979) you can see the more mature poet playing with the same method of building a poem, only now in a more intricate fashion:

Outside the kitchen window a black rat

Sways on the briar like infected fruit:

‘It looked me through, it stared me out, I’m not

Imagining things. Go you out to it.’

Did we come to the wilderness for this?We have our burnished bay tree at the gate,

Classical, hung with the reek of silage

From the next farm, tart-leafed as inwit.

Blood on a pitchfork, blood on chaff and hay,

Rats speared in the sweat and dust of threshing –

What is my apology for poetry?The empty briar is swishing

When I come down, and beyond, inside, your face

Haunts like a new moon glimpsed through tangled glass.

A poem such as this becomes almost mathematical in its precision. On the way downstairs the writing “I” of the poem has identified himself with the small, exposed and wordless living thing, the rat: at the end of the poem the “I” looks up at the window, himself in the position of the rat. In the last stanza the poet has traded places with the rat itself, the intruder, that threatening piece of nature.

Halfway there you find the real hinge of the poem, the place where things trade places: the “bay tree”, symbol of poetry and a classic heritage, “reek with silage”. A familiar, rural smell, in itself a modern phenomenon of the countryside, is projected onto the symbol of antiquity. And the moral problem from the poem ‘Digging’ presents itself again.

Blood on a pitchfork, blood on chaff and hay,

Rats speared in the sweat and dust of threshing –

What is my apology for poetry?

Does poetry need an excuse? Or a defence: the word “apology” is, of course, ambiguous. In the sheer face of bloody violence, the everyday slaughter in the farmyard or the political violence of Irish history, past and present – what place is there for poetry at all, what role can this heightened form of language play in the face of crisis, death, distress?

This is the question addressed in one of Heaneys’ best essays on literature and the ‘meaning’ of poetry, ‘Feeling into Words’ (in Preoccupations, 1980). He takes his starting point in a quote from one of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, number 65: “How, with this rage, shall beauty hold a plea?”

This question is central to Heaney’s own poetry and to his prose writings about his own poetry and that by others: among his close, literary ‘relatives’ you find a number of other Nobel Laureates, such as Joseph Brodsky, Derek Walcott and Czesław Miłosz. How then should beauty, or poetry, hold a plea?

The answer, that slowly works its way to the surface in all of Heaney’s writings, is quite straightforward. By showing us things as they are.

As he writes in another of the ‘Glanmore Sonnets’, which takes its poetic impulse from the BBC weather report:

Dogger. Rockall. Malin. Irish Sea:

Green, swift upsurges, North Atlantic flux

Conjured by that strong gale-warning voice,

Collapse into a sibilant penumbra.

(…)L’Etoile, Le Guillemot, La Belle Helene

Nursed their bright names this morning in the bay

That toiled like mortar. It was marvellous

And actual. I said out loud, ‘A haven,’

The word deepening, clearing, like the sky

Elsewhere on Minches, Cromarty, The Faroes.

The “actual” is “A haven”. Heaney creates a way in which you learn to see the actual world around you, in a new light. But “seeing” in the Heaney sense can mean two things, two concepts which we find in the centre of modernist poetry; ‘epiphany’ and ‘correspondence’.

It is quite simple: ‘epiphany’ is here, as in the works of James Joyce and Tomas Tranströmer, the moment where you experience a sudden insight into the meaning of things seemingly trivial, for example the BBC weather forecast –how it in itself can contain a world of life, of thousands of living people along a coastline, exposed to the same weather, something very real as the rain and the wind – as opposed to strange political ideas of ‘purity’, ‘nation’ or ‘race’. A haven.

‘Correspondence’, on the other hand, is when you realise previously invisible connections between things, connections perhaps only made possible through the special kind of language we call poetry. The most obvious case of correspondences in Heaneys’ work you find in the suite of poems he wrote in the early seventies, where he – again like Tranströmer – shows his fascination with the ‘bog bodies’, the startlingly well-preserved remains of prisoners executed and buried in peat bogs in Denmark in prehistoric times. The most well known example is ‘the Tollund man’, who was strangled somewhere around the year 350 B.C., and was sunk into a peat bog outside of Silkeborg in Denmark.

The custom of human sacrifice combined with the burial of the victims in bogs is connected to the Celtic culture of the time, a point driven home by Heaney in his poems about the ‘bog bodies’ in Wintering Out (1972) where he openly compares the – in our eyes – senseless murder of human beings, for the sake of an abstract god or goddess, to the slaughter of men and women, for the abstract ideas of nationalism and loyalism, in his own contemporary Ulster.

The here and now is a sanctuary, we live in a real world, it has to be seen, you have to experience its stark reality if you are not to succumb to seductive ideologies. But, on the other hand: everything you see is in itself connected to a vibrating sense of history, everything has meanings beyond itself, and beyond your own life. That is the paradox, if you will, that you find in Heaney’s earlier poetry.

But a paradox can, strangely enough, be something very stable. You have ‘this’ on the one hand, and ‘that’ on the other. The first phase of Heaney’s poetry can rest almost comfortably in that kind of balance. A metaphor is introduced in the first stanza and recurs, with its meaning turned inside out, in the last. This kind of irony has its place. But Heaney’s poetry has continued to grow and change. It has become more restless.

This change is visible in a collection like Electric Light from 2001. Nothing has been lost, but new elements have been added. In the poem that gives the book its title, you recognize the ‘old’ Heaney:

In the first house where I saw electric light,

She sat with her fur-lined felt slippers unzipped

Year in, year out, in the same chair, and whispered

In a voice that at its loudest did nothing else

But whisper.

In this poem you see the weaving together of the old, rural community – here represented by the poets’ grandparents, the oral storytelling, the old farmhouse with the stable on the other side of the bedroom wall. And the electric light, the “wireless” set with its green eye and voices from afar. Vintage Heaney.

But in the same volume you also find a poem like ‘The Loose Box’ – a strange, winding tale that starts out in an ordinary, abandoned stable, somewhere in the northern Irish countryside – and then moves on to the birth of Jesus on a bed of straw, in another stable – and then covers the fall of Troy (with the use of a wooden horse, filled with straw), to the death of Irish revolutionary Michael Collins in the civil war – and his own background in the countryside, in the stable, on the straw. You could boil it all down to one sentence: “all flesh is straw” – but it is not a stable poem in the way that Heaney’s poems used to be stable. Something happens here, in a pun or word-play with the word “stable” – and all of history comes undone, spilling into the poets’ own biography, spilling straw. It is a magnificent poem. It is like seeing a sail flapping in the wind, not because the ship has lost its momentum but because it is ready to change its course.

This tendency to outgrow the balances and ironies of the earlier phases is very visible in Seamus Heaney’s latest collection to date, District and Circle (2006). The district and circle in the title shows itself to be the subway system, subterranean connections deep underground. All the elements from his earlier works are very present, like in the opening poem about the old “turnip-snedder”, an ancient piece of farming machinery that sits abandoned in a barn somewhere – but still loaded with meaning and threat, as being watched by a child that now has grown up to become a poet: “this is the way that God sees life.” A churning mechanism, impersonal, forceful, ready to crush turnips and boys’ fingers alike.

District and Circle is also a book that digs deeper and deeper into memory: it recalls boyhood encounters, the American presence in Northern Ireland during World War II, even the ‘Tollund man’ himself makes a guest appearance. But the very method of this ‘new’ poetry is not to balance things evenly on a scale, but to make them merge, go up into each other.

This is very visible in the subway poem. Heaney has written about the “underground” before, in the opening poem of Station Island (1984) where the poet, hurrying through the London subway, finds himself transformed into Orpheus, dreading the moment when he has to look back over his shoulder.

That was a poem about death, about loss. The same is true about District and Circle: the “underground” is here the realm of the dead, too, something that becomes apparent in the opening lines:

Tunes from a tin-whistle underground

Curled up a corridor I was walking down

Where the eerie music at the same time is that of a street musician and at the same time the alluring music of the “people underground”, the Tuatha de Danaan of Irish folk lore. The poem goes on in the same vein, with the vendor in the ticket booth being Charon, which is obvious without the poet mentioning it. Stepping onto the subway carriage becomes the passing on, with all the other passengers, to another destination:

My back to the unclosed door, the platform empty;

And wished it could have lasted

… and the poet sees his father’s face in his own reflection in the window, it all leading up to the final stanza:

And so by night and day to be transported

Through galleried earth with them, the only relict

Of all that I belonged to, hurtled forward,

Reflecting in a window mirror-backed

By blasted weeping rock-walls

Flicker-lit.

The distance between language and world is gone. The subway train is a subway train, no more, no less; at the same time the voyage is a ritual passing from life to death, a fact that is stated nowhere in the poem, but nonetheless becomes obvious to the reader. The train is no ‘metaphor’ for death, it is death.

This transformation is present in all the best poems in the volume. ‘Poet to blacksmith’ claims to be a translation of a letter from the Irish-speaking, 18th century poet Rua Ó Súilleabháin to his blacksmith, asking for a new kind of spade, perfect, shining, with “no trace of hammer to the blade”.

And best thing of all, the ring of it, sweet as a bell

The reader has no problem here recognizing the spade from ‘Digging’. It is no longer a question of pen and spade trying to coexist, or doing ‘the same thing’. They now are the very same thing. The gap has, in one way at least, finally been bridged. By poetry itself.

As in ‘A Shiver’. On the surface, a poem about knowing your tools, about craftsmanship or silent knowledge: deeper down, about a labour that has been there all the time, throughout forty years of writing:

The way you had to stand to swing the sledge,

Your two knees locked, your lower back shock-fast

As shields in a testudo, spine and waist

A pivot for the tight-braces, tilting rib-cage;

The way its iron head planted the sledge

Unyieldingly as a club-footed last;

The way you had to heft and then half-rest

Its gathered force like a long-nursed rage

About to be let fly: do you good

To have known it in your bones, directable,

Withholdable at will,

A first blow that could make air of a wall,

A last one so unanswerably landed

The staked earth quailed and shivered in the handle?

Poetry is that shiver in the handle.

References

Death of a Naturalist (Faber & Faber, 1966).

Wintering Out (1972).

Field Work (Faber & Faber, 1979).

Preoccupations (essays, Faber & Faber 1980).

Electric Light (Faber & Faber, 2001).

District and Circle (Faber & Faber, 2006).

* Ola Larsmo (b. 1957), writer and literary critic. Between 1984–1990 Larsmo was editor of BLM (‘Bonniers Literary Magazine’). Today he writes literary criticism in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter. Ola Larsmo has published some fifteen books, alone and in collaboration with others, mainly novels, but also essays on contemporary Irish and Swedish literature and on the subject of the Internet and democracy. His latest novel is En glänta i skogen (‘A Glen in the Forest’, 2004). In the fall of 2007 it will be followed by Djävulssonaten (‘The Devil’s Sonata’).

First published 20 February 2007

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.