Imre Kertész

Article

Imre Kertész: A Medium for the Spirit of Auschwitz

by Madeleine Gustafsson*

This article was published on 17 November 2003.

Imre Kertész was born in Budapest on November 9, 1929. Not yet fifteen years old, he was deported together with 7,000 other Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, and thence to Buchenwald, where he was liberated in 1945. On returning to Hungary, he worked for a few years at the newspaper Világosság, but was fired in 1951 and drafted for two years of military service. Since 1953 he has lived in Budapest (and after 1989 often in Berlin) as an independent writer and a translator of German-language literature – in daily dialogue with such great kindred spirits as Mann, Kafka and Nietzsche while working on his own writing. In 2002 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Novels

It took Kertész almost as long as he had lived before his deportation, fourteen years, to write his debut book. It was rejected by a state-owned publishing company, came out anyway in 1975 in a modest edition, but encountered a compact silence. In Sweden, it was published for the first time in 1985 by Fripress in Maria Ortman’s translation, under the title Steg för steg (Step by Step). At first, it did not attract much attention in Sweden either, even though aside from Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, it is certainly the most powerful literary account of the reality in a concentration camp ever written.

The fact that Kertész himself was deported does not mean that Fateless (or Man Without a Fate, as it was renamed – more closely reflecting the original title) is autobiographical in any simple sense. He deliberately leaves out everything anecdotal, temporary, all exceptions in favor of banality (if one can speak of banality in this context): a methodical account and analysis of actual life in the camp, of the totalitarian structure.

A most powerful literary account of the reality in a concentration camp ever written.

Copyright © Northwestern University Press

It is also very different from Levi’s narrative, if we disregard the content, the overly familiar: how a human being is captured, removed from his ordinary existence and gradually adapted to another existence, whose only purpose is to crush and eventually kill him. But Primo Levi was a grown man. Köves, the narrator in Fateless, is fourteen, and the year from 1944 to 1945 is the decisive learning year of his life.

Together with a group of boys of the same age, he is rounded up in a bus during a raid in Budapest in 1944. First they are locked up for one warm, tedious day in a customs house, while a befuddled young policeman phones for more detailed instructions. Then they are detained for a few days in an old brick factory, to which several thousand Jews are eventually brought. After discussions with the Jewish Council, they accept an “offer” to enlist voluntarily for work service, since the trains, as it is explained to them, will undoubtedly be more crowded later on. “There was therefore really not much room for consideration.”

When liberation reaches Köves one year later, he is lying in the hospital barracks at Buchenwald, the only survivor among his group of friends, a yellowish skeletal figure with a pointy old man’s face and festering sores everywhere under his skin.

Terribly Provocative Tone

Kertész’ novel is not a difficult read, not in a technical sense. It is a straightforward, meticulous narrative, without digressions and without comments, other than what the age and limited experience of the main character make probable. The tone is vigorous and curious, almost ingenuous. It is the tone of a young person who, in every new situation, struggles to understand and to do his best, not out of naiveté, but in order to survive. To him, everything actually unfolds “step by step.” And his initial reactions are almost of frightened admiration: just think how clever they were to persuade him to take off his clothes before the shower, by asking him to memorize the number on the hanger and to tie together his shoes! Someone must have worked this out… They undoubtedly use the same method in other shower rooms where, he is told, they don’t pour water but instead release gas on the prisoners. And the drill in the work camp – what a difference, compared to the Hungarian policeman’s clumsy awkwardness! How smoothly and efficiently everything works! When the prisoners eventually lose their stamina and grow so thin as to be unrecognizable, this also happens so gradually that he doesn’t notice it, except in comparison with the unspoiled appearance of the German guards, almost as if they were a different kind of people.

To someone with this wide-open, indeed eager curiosity, every situation is genuinely new, a now without the retrospective knowledge that we possess, but which the narrator does not.

It is a terribly provocative tone. Kertész also sticks to it consistently, with a kind of harshness that makes it credible.

But the most challenging thing, the reason why the book was so coldly received when it came out, was something else, I believe. It is summed up in the title: Fateless. Or: a man without a fate. Because it is not only about Auschwitz, about something that happened, but about a philosophy of life. The boy tries to express this after returning home to Budapest. It was not really true, he said, that it just came: they also went. Step by step. Only in retrospect does everything seem finished, completed, incomprehensible, possible to summarize (and keep at a distance) in words like “horrors” or “hell.”

Granted, he has lived through a given fate. It was not his predetermined “fate” but he was the one who lived through it. And now he was forced to do something with all these steps he had taken. They must not be completely meaningless. He cannot satisfy himself by saying it was a mistake, or accepting the silly bitterness of merely being innocent. Why didn’t anyone want to understand this: if there is fate, freedom is not possible; but if there is freedom, there is no fate. In other words, he tells his increasingly distressed listeners: “we ourselves are fate.”

“At this point, not only Uncle Steiner but also Uncle Fleischmann jumped up. ‘What?’ he roared to me with a fiery-red face, ‘are we now the guilty ones – we, the victims?'” He tried to explain that it was not a matter of guilt. That they should just realize it, humbly and simply, for the sake of meaning itself, out of pure honesty, so to speak.

As Kertész writes in his Galley Diary: “Fateless is a proud work. Because of that, people will never forgive either the book or me.”

“The Pen Is My Spade”

If Fateless is provocative, Kaddish for a Child not Born leaves one almost dumbstruck.

It is a thin little book, a single long, droning distraught monologue that never lets go, a little like the books of Thomas Bernhard. The meandering but, in all its complexity, completely clear prose, has a suggestiveness that also pulls the most reluctant reader into its argumentation. If something would make it relax and give the reader breathing space, paradoxically it would certainly be a single breath of literature, a desire for effect – but the author energetically resists anything like this, in the same way as he resists all escapes, all conciliation, all mercy. He is logical, objective, implacable.

A “kaddish” is a Jewish prayer for the dead. But what the speaker says here is aimed at a child who was never allowed to be born, a child that the speaker cannot possibly imagine being the father of. After all, bringing a child into the world implies that in some sense, you will live on after your death, but for the speaker, that perspective is inconceivable. This is because in a way, he has already survived his death. Someone once began to dig his grave (“in the breezes” as Paul Celan’s Death Fugue puts it), “then …placed the tool in my hand, thereby leaving me alone to complete the job they had begun, as best I could.”

|

| Nusach Sepharad (Mourner’s Kaddish) and the English translation below. Copyright © World ORT 2001 |

May His illustrious name become increasingly great and holy

In the world that He created according to His will, and

may He establish His kingdom

And may His salvation flourish and the Messiah come soon

In your lifetime and in your days

and in the lifetime of all the house of Israel

Speedily and soon. And say amenMay His illustrious name be blessed always and forever.

Blessed, praised, glorified, exalted, extolled

Honoured, raised up and acclaimed

be the name of the Holy one blessed be He

beyond every blessing hymn, praise and consolation

that is uttered in the world. And say amenMay abundant peace from heaven, and good life

Be upon us and upon all Israel. And say amenMay He who makes peace in His high places

Make peace upon us and upon all Israel,

And say amen

So in practice, this is how the philosophical conclusion of Fateless looks: the choices is between viewing one’s existence as an arbitrary and meaningless accident, a series of coincidences “which despite everything would be, how shall I put it, a fairly unworthy way of viewing life”, or living with the direction life has now taken and giving it whatever meaning it can have, in this case by writing. “The pen is my spade,” writes Kertész. Writing becomes his way of continuing his digging and trying to transform his life into “a series of insights, where my pride, at least my pride, finds satisfaction.”

And his insights? The insight, as the speaker in Kaddish uses all his persuasive power to convey and emphasize to his wife, the reader, and perhaps also himself, is that there is nothing unexplainable about Auschwitz. Auschwitz existed and was thus not a product of any “incomprehensible” forces. Instead it was fully comprehensible and derivable from the world such as it looks, “for what is is; and its very existence is necessitated by the fact that it is.” Evil is neither an accident nor a mistake, but a consequence of rational thinking by individual people. As an abominable logical possibility, Auschwitz has been hanging in the air (“for a long, long time, centuries…”) while waiting for the right time to materialize. This is how the world looks, how our civilization looks. However, what does require an explanation, the speaker says, “and now you should listen extra carefully”: the really irrational thing that interrupts the regular mechanical process in an inexplicable way is not evil but, on the contrary, goodness. Goodness is not rational, and there is no explanation for goodness.

And the reader must really “listen extra carefully.” The episode about the fellow prisoner who, despite having a chance (a chance that in Auschwitz could mean the difference between life and death) did not snatch the narrator’s food ration for himself but even risked his life to make sure that he got it back (with the single indignant comment: “Well, what did you expect?”) lies hidden in the middle of the monologue and is easy to overlook, since it is told against the grain, so to speak. It is more a question than a statement, a drop in a river of rage, but it is there. And it doesn’t say that the world is good. All it says is that freedom exists.

A thin little book, a single long, droning distraught monologue that never lets go.

Copyright © Northwestern University Press

This defiant freedom is also what Kertész’ second novel, Fiasco (1988), was about: a freedom whose paradoxical nature consisted of willingly choosing an almost prison-like life in order to make writing possible, voluntarily settling into an existence that is shabby and surrounded by external stresses and material difficulties, which – under the prevailing totalitarian regime – was the only alternative to collaboration. During the 1956 revolt, Kertész’ alter ego Köves has a chance to leave the country but chooses to stay to write his novel, “the only novel that is possible for me,” in the only language he knows. But before this he has had time to try – and fail at – all the opportunities for social adjustment that have been available to him: working as a journalist, being a metalworker, even a prison guard, before he is finally ready for total refusal – a total refusal to be useful – which is his salvation.

Fiasco is a Kafka-like account, almost jovial in its unrelentingly pessimistic clarity, of the Communist dictatorship, which is portrayed almost as an uninterrupted continuation of life in the camp – which in turn, in Kaddish, is depicted as a continuation of the patriarchal dictatorship of a joyless childhood. The three novels thus become a coherent whole, an extension of Kertész’ fundamental and in some sense only theme: the totalitarian experience, Auschwitz as trauma not only for an individual but for the whole civilization – ours – that made Auschwitz possible.

Intellectual Prose

Concurrently with his novels, Kertész has written intellectual prose – a kind of workbooks about reading, writing and death. An initial selection, covering the period between 1961 and 1991, came out in 1993 under the title Galley Diary. A second, entitled I, Another, was published in 1997. The first book mainly commented on his life and thoughts while writing the novel trilogy. The second focused on the major changes in his (and the European continent’s) existence after 1989. He has also published several collections of essays and speeches, entitled (in German) Der Spurensucher (The Pathfinder), Die englische Flagge (The English Flag), Eine Gedankenlänge Stille, während das Erschießungskommando neu lädt (Moments of Silence While the Execution Squad Reloads) and most recently Die exilierte Sprache (The Exiled Language).

The paradox about writing that Kertész repeatedly formulates cannot be summarized, for it is a genuine paradox, but it can be described with the help of two quotations that must be viewed as simultaneously valid.

The first is from Galley Diary: “If I think about a novel, I again think about Auschwitz. Whatever I think about, I always think about Auschwitz. Even if I am seemingly speaking about something completely different, I am speaking about Auschwitz. I am a medium for the spirit of Auschwitz. Auschwitz speaks through me. Everything else seems stupid to me, compared to that.”

The second is taken from his speech at the Swedish Academy’s symposium “Witness Literature” in December 2001, where he says that “it is impossible not to write about the Holocaust, impossible to write about it in German, and equally impossible to write about it any other way,” because, he continues, those who write about the Holocaust in whatever language always write in a foreign language, in exile from a homeland that has never existed.

|

| “I am a medium for the spirit of Auschwitz. Auschwitz speaks through me. Everything else seems stupid to me, compared to that.” – Imre Kertész. |

This stubborn writing, which never gives up until it has managed to scrape its way to the raw cliff wall of naked existence, thus moves between impossibilities. It is a penetrating and thoughtful intellectual prose, which unrelentingly feels the pulse of the writer as well as the reader, using words as a painful but demanding shield against (to quote from I, Another) “the ‘desolate land’ where they no longer speak, but only murder.”

Translation from Swedish by Victor Kayfetz.

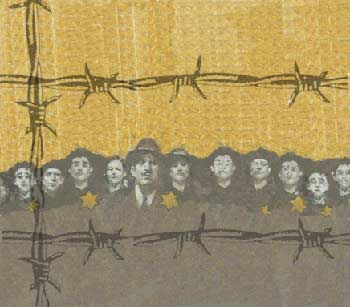

Efforts have been made to give credit to the image on the Holocaust appearing in this article. This omission will be rectified as soon as proper information is available. – Publisher

* Madeleine Gustafsson (b. 1937) writer, literary critic and translator, lives in Stockholm, Sweden. She received her Bachelor’s degree from Uppsala University in 1961 and served as literary critic for the following newspapers: Uppsala Nya tidning (1960-62), Stockholmstidningen (1963-64), Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning (1963-73), BLM and Dagens Nyheter since 1973 up to the present.

Gustafsson was a member of the Committee for Literature and Library (1978-80), was board member of Författarfonden (Writers’ Foundation) in 1980-84 and is currently member of Samfundet De Nio, a writers guild based in Stockholm.

Her published works include essays (in Swedish): Med andras ögon (1978), Utopien och dess skugga (1978), Berättelsens röst (1991); poetry: Solida byggen (1979), Vattenväxter (1983), Fång-lada (1993). In German, in the translation of Verena Reichel Die Lawine hinauf (1988). She has also translated to Swedish from German, French and Italian the works of such literary figures as Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Marguerite Duras, among others.

First published 17 November 2003

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.