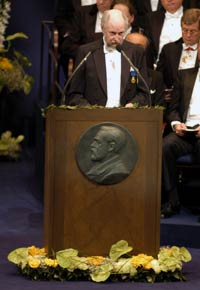

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Torgny Lindgren of the Swedish Academy, December 10, 2002.

Translation of the Swedish text.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2002

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The realities that are the subject of Imre Kertész’s literary production and form its background cannot be understood or described by any of us who have not experienced them. The bestial, systematic evil of Nazism and the bureaucratic, misanthropic stupidity of the socialistic one-party state are hardly comprehensible to minds that have been shaped in civilized societies: nor do they allow themselves to be portrayed in other ways than as crazy paradoxes and absurdities.

Imre Kertész has written about this artistic problem in his Galley Diary and in his essay collection Eine Gedankenlänge Stille.

It has often been argued that Fateless is the hub and center of Kertész’s literary production. That may be correct: this ostensibly simple, naked and mundanely unassuming account of a young boy’s life and sufferings in Auschwitz, Zeitz and Buchenwald possesses a weightiness and irrefutability that puts it not only at the core of one man’s literary production but also of contemporary European prose.

“When you are going to read Kertész, you have to begin with Fateless!” is a very common statement. However, it can be called into question.

No matter which Kertész novel or essay we pick up, we soon notice that it is intimately connected to one of the other works in his literary production. In a manner that is hard to explain, the separate parts appear to have grown together, with common root fibers or circulatory systems. Fiasco, that many-voiced, off-center account of a system-critical writer’s desperate hardships in a totalitarian, anti-educational state, is linked by allusions and thematic details with The English Flag, which in turn is intimately connected to the much later book of thoughts Galley Diary. From Kaddish for a Child Not Born, a mournful and simultaneously ironic requiem for a child who is never allowed to be born, because it would be cruel and criminal to bring it into the world, there are delicate but easily discernible threads that link it to Fateless and Fiasco.

What finally reveals itself to the reader is a coherent organism, a body or symphonic work in the spirit of Mahler or Webern. Or in a word that borrows its solemn tone from the aging Thomas Mann: Ein WERK. An oeuvre, whose subject is an individual’s refusal to abandon his individual will by merging it with a collective identity.

And behind each text, we clearly hear a voice or tone that Kertész himself has formulated this way: In all respects my existence is horrible, except for writing: so I write and write to endure my existence, to justify it.

Kertész approaches tradition in a similar contrapuntal way. In his world, tradition is not a temporal phenomenal, but a spatial one. Tradition is his surroundings, the landscape where he resides and where on his rambles he encounters social companions and conversational companions like Camus, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, St. John of the Cross, Kafka or Paul Celan.

Sehr verehrter Imre Kertesz!

Uns, die wir Ihrer Dichtung begegnet sind und den Vorteil hatten uns in sie zu vertiefen, scheint sie notwendig und unentbehrlich um das “20. Jahrhundert, das wir noch unser eigenes nennen müssen, zu verstehen. Und das um so mehr, um auch das Schwanken zwischen Schicksal und Freiheit zu begreifen, welches das Los des preisgegebenen und wehrlosen Menschen während dieses Jahrhunderts gewesen ist. Es war und ist eine Zeit, die scheinbar Ihre Hypothese bestätigt, dass der Affe vom Menschen abstammt und nicht umgekehrt. Hinter diesem Gedanken, der ein wenig misanthropisch vorkommen mag, hört man deutlich den milden und klugen Humor, der Ihr ganzes schriftstellerisches Werk durchströmt.

Sie haben auch einmal geschrieben: Ich werde immer ein zweitrangiger, verkannter und missverstandener ungarischer Schriftsteller sein; die ungarische Sprache wird immer eine zweitrangige, verkannte und missverstandene Sprache sein.

Gegen diese ironische Behauptung möchte die Schwedische Akademie am kräftigsten protestieren und Ihnen gleichzeitig herzlich gratulieren, wenn ich Sie jetzt auffordere, den Nobelpreis für Literatur aus der Hand Seiner Majestät des Königs entgegenzunehmen.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.