Camillo Golgi

Article

by Marina Bentivoglio

This article was published on 20 April 1998.

Life and discoveries of Camillo Golgi

Biographical sketch and scientific work

Camillo Golgi was born in July 1843 in Corteno, a village in the mountains near Brescia in northern Italy, where his father was working as a district medical officer. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia, where he attended as an ‘intern student’ the Institute of Psychiatry directed by Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909). Golgi also worked in the laboratory of experimental pathology directed by Giulio Bizzozero (1846-1901), a brilliant young professor of histology and pathology (among his several contributions, Bizzozero discovered the hemopoietic properties of bone marrow). Bizzozero introduced Golgi to experimental research and histological techniques, and established with him a lifelong friendship. Golgi graduated in 1865 and was, therefore, a student during the last years of the fights for the independence of Italy (Italy became united in 1870).

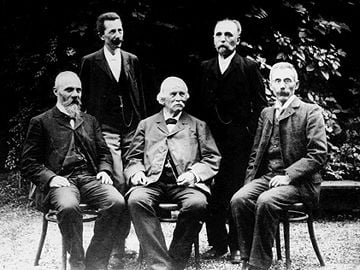

Seated left to right: Perroncito, Kölliker, Fusari

Standing left to right: Bizzozero, Golgi (here in his late fifties).

Golgi started his scientific career in 1869, with an article in which, influenced by Lombroso’s theories, he stated that mental diseases could be due to organic lesions of the neural centers. However, convinced that theories had to be supported by facts, Golgi soon abandoned psychiatry and concentrated on the experimental study of the structure of the nervous system. Histological techniques, such as fixation procedures and tissue stainings (hematoxylin or carmine) had been introduced in the middle of the 19th century. However, these procedures were inadequate and unsatisfactory for the investigation of the structure of the nervous system, due to its complexity and peculiar organization in respect to other tissues.

Camillo Golgi

In 1872, due to financial problems, Golgi had to interrupt his academic commitment, and accepted the post of Chief Medical Officer at the Hospital of Chronically Ill (Pio Luogo degli lncurabili) in Abbiategrasso (close to Pavia and Milan). In the seclusion of this hospital, he transformed a little kitchen into a rudimentary laboratory, and continued his search for a new staining technique for the nervous tissue. In 1873 he published a short note (‘On the structure of the brain grey matter’) in the Gazzetta Medica Italiana, in which he described that he could observe the elements of the nervous tissue “studying metallic impregnations… after a long series of attempts”. This was the discovery of the ‘black reaction’1 (reazione nera), based on nervous tissue hardening in potassium bichromate and impregnation with silver nitrate. Such revolutionary staining, which is still in use nowadays and is named after him (Golgi staining or Golgi impregnation) impregnates a limited number of neurons at random (for reasons that are still mysterious), and permitted for the first time a clear visualization of a nerve cell body with all its processes in its entirety.

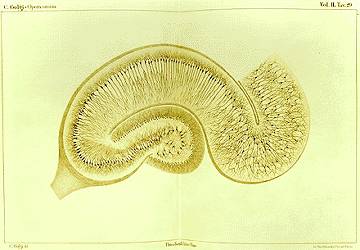

Hippocampus impregnated by the Golgi stain (from an original preparation from Golgi’s laboratory kept in the Institute of Pathology of the University of Pavia).

Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. The Golgi stain reveals their extensive dendritic branches (from an original preparation from Golgi’s laboratory kept in the Institute of Pathology of the University of Pavia).

In 1875 Golgi published, in an article on the olfactory bulbs, the first drawings of neural structures as visualized by the technique he had invented. In 1885, Golgi published a monograph on the fine anatomy of the central nervous organs, with beautiful illustrations of the nerve centers he had studied with his method.

Golgi’s drawing of the hippocampus impregnated by his stain (from Golgi’s Opera Omnia).

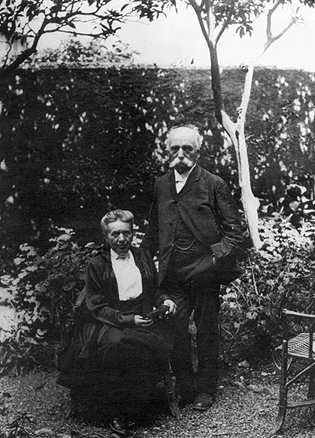

In the same year, Golgi returned to Pavia, where he was appointed in 1876 as Professor of Histology. In 1877 he married Lina Aletti (Bizzozero’s niece). They had no children, and adopted Golgi’s niece Carolina.

Camillo Golgi and his wife Lina by the sea in his late seventies.

In 1881 Golgi was appointed to the chair of General Pathology at the University of Pavia, and he also maintained his teaching in histology.

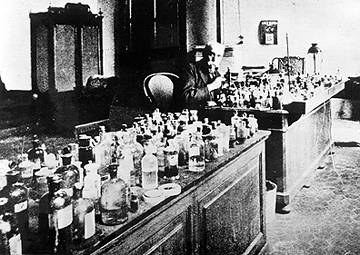

Golgi at the age of 77 in his laboratory in Pavia.

Golgi established in the Institute of General Pathology a very active laboratory, with international contacts, and was especially gifted in stimulating his students and foreign guests, including the Norwegian histologist and explorer Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930), Nobel Laureate in Peace 1922. In Golgi’s laboratory, Adelchi Negri (1876-1912) discovered the intraneuronal inclusions (the Negri bodies) which represent specific features of rabies and provided a histopathological diagnostic criterion for such infection. In Golgi’s laboratory, Emilio Veratti (1872-1967), described for the first time the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle fibers. In 1906 Golgi shared the Nobel Prize with Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) for their studies on the structure of the nervous system.

The Nobel diploma Golgi received in 1906.

© The Nobel Foundation 1906, Artist: Olle Hjortzberg, Courtesy: Museum of the History of the University of Pavia

Highly respected, Golgi was dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Pavia, and rector of this university for several years. Golgi also received honours from several European universities. He took an active part in public life; he was especially concerned with public health, and became a senator in 1900. He retired in 1918 but remained as professor emeritus at the University of Pavia. Golgi died in Pavia in January 1926. His publications are collected in the Opera Omnia (published by Hoepli Editore, Milan). The first three volumes of Opera Omnia appeared in 1903 and the fourth volume was edited by Golgi’s co-workers (L. Sala, E. Veratti, G. Sala) and appeared in 1929.

Scientific debates and the impact of Golgi’s discoveries

Golgi’s discovery of the black reaction and his subsequent investigations provided a substantial contribution to the advancement of the knowledge on the structural organization of the nervous tissue. The theory that tissues are composed of individual cellular elements (the cell theory) had been enunciated in 1838-1839 by Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) and Theodor Schwann (1810-1882), but had not been extended to the nervous tissue. However, Golgi believed that his own observations of ramified nerve fibers could support the ‘reticular theory’, which postulated that the nervous system was a syncytial system, consisting of nervous fibers forming an intricate network, and that the nervous impulse propagated along such diffuse network. In the meantime, the theory that the nervous system as the other tissues was composed of cells, which were christened as ‘neurons’ by Wilhelm Waldeyer (1836-1921) in 1891, was receiving wide support, also from studies pursued in other laboratories by means of the Golgi’s new staining. Cajal was the main supporter of the ‘neuron theory’, which correctly interpreted the nervous system as composed of anatomically and functionally distinct cells, not in cytoplasmic continuity.

Human cerebellar cortex as drawn by Golgi (from the Opera Omnia).

Golgi was an exceptionally acute and prolific investigator, who provided a number of outstanding observations. Although he misinterpreted the overall view of the organization of the nervous system, he contributed highly to the modern knowledge of its structure. Among other findings, Golgi described the morphological features of glial cells (that are also impregnated by his staining) and of the relationships between glial cell processes and blood vessels. He also described two fundamental types of nerve cells, still named after him as neurons ‘Golgi type I’, extending their axons at a distance from the cell body (the ‘projection neurons’ of the modern nomenclature), and ‘Golgi type II’, with axons ramifying in the vicinity of the cell body (corresponding to the ‘local circuit neurons’ and ‘interneurons’ of the modern nomenclature).

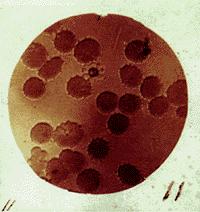

Among his other discoveries, in 1878 Golgi described the tendinous sensory corpuscles that bear his name (the Golgi tendon organs). In the years 1886-1892, Golgi provided fundamental contributions to the study of malaria: he elucidated the cycle of the malaria agent, the Plasmodium, in red blood cells, and the temporal coincidence between the recurrent chills and fever with the release of the parasite in the blood. Golgi also studied the efficacy of the administration of quinine during the disease.

Golgi’s drawing of the tendon organ that now bears his name (from Opera Omnia).

A typical rosette-shape of the malarian parasite on the top, among red blood cells. Photograph of an original Golgi preparation preserved at the Museum for the History of the University of Pavia.

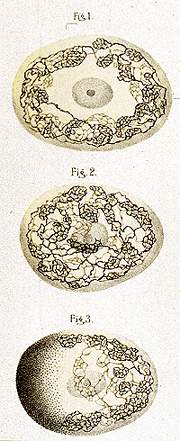

In 1897, studying the nervous system with his black reaction, Golgi noticed in neurons an intracellular structure, whose existence he officially reported in April 1898. This structure was designated by Golgi “internal reticular apparatus” and was soon named after him as Golgi apparatus (or much later as the Golgi complex and is frequently referred to nowadays only as “the Golgi”). The discovery of this cell organelle was a real breakthrough in cytology and cell biology. However, the existence of the Golgi apparatus was debated for decades (many scientists believed that it only represented a staining artefact) and was only confirmed in the mid-1950s by the use of the electron microscope. The Golgi apparatus plays a key role in the intracellular sorting, trafficking and targeting of proteins. This organelle makes Golgi the most frequently cited scientist in cell and molecular biology. The year 1998 marks the centenary of this discovery, celebrated in many scientific journals and meetings.

Golgi’s drawings of the “internal reticular apparatus” that he observed in spinal ganglia (the different drawings illustrate the variety of features Golgi observed with his metal impregnation, from Opera Omnia). This intracellular structure is universally known nowadays as “Golgi apparatus”.

Rigorous, determined, highly motivated scientist and stimulating teacher, Golgi left a heritage of passionate studies that exerted a profound influence on biomedical research in the 20th century.

The Golgi Hall in the Museum for the History of the University of Pavia. In the “high altar” (to the right), exclusively devoted to Golgi, his Nobel diploma can be seen.

The Italian ‘Ufficio Principale Filatelico’ issued this stamp in 1994 to celebrate the Nobel Laureate Camillo Golgi.

Reproduced with the permission of Mrs Maria Ciraci, The Director of Ufficio Principale Filatelico, Rome, Italy.

1. The Black Reaction – La reazione nera

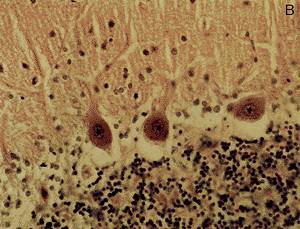

The Purkinje cell of the cerebellum is used as an example to illustrate the revelatory power of the Golgi stain, and why it was and still is important. The extension and orientation of dendrites of the Purkinje cells provided a key for the understanding of how the cerebellar cortex is built up and works (the same could be stated for all other structures of the brain, in which how neuronal processes are arranged is the prerequisite for their functioning). The anatomist Evangelista Purkinje described the large cells in the cerebellum (A) that bear his name. With the methods available at Purkinje’s time, he could only observe the cell bodies. No branches can be seen even in the routine histological stains (thionin, cresyl violet) still used nowadays (B). C demonstrates that the Golgi stain fully visualizes the entire extent of ramifications of this particular neuronal cell type and its spatial orientation. This is crucial for the functioning of the cerebellar cortex, since the axons of granule cells (called parallel fibers) coursing tangentially establish several hundred thousands of contacts with the dendrites of each Purkinje cell (D).

A depicts the Purkinje cell as Evangelista Purkinje described and drew in 1837.

B illustrates the cerebellar cortex in a routine histological stain (Nissl stain) still commonly used nowadays: in the upper part of the photo the molecular layer (with very few cells, indicated by their nuclei – the dark dots – ) can be seen, then there is the Purkinje cell layer (with three large cell bodies visible) and then the granule cell layer (with densely packed small cells). With this stain, dendrites of Purkinje cells extending into the molecular layer can hardly be identified.

C illustrates a Golgi-impregnated Purkinje cell with the full extent of its dendritic arborizations.

Reproduced with the permission from FUNDAMENTAL NEUROANATOMY by Nauta and Fiertag 1986 by W. H. Freeman and Company. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

D illustrates the general organization of cerebellar cortex and shows the crucial role played by the ramifications of the Purkinje cells and their spatial orientation.

The ‘impact’ of the knowledge of the cell architecture and the orientation of its dendrites on the clarification of the structure and function of the cerebellar cortex is explained in this drawing of the cerebellar cortex (D). Without knowing how and where the individual cell bodies extend their processes it would have been very hard to have clues on the organization of the cerebellar cortex. The same applies to all the other neural structures.

Credits

Thanks are due to Dr. Paolo Mazzarello for his help and advice.

Photos were kindly provided by Museo di Storia dell’Università di Pavia – Museum for the History of the University of Pavia, Director: Dr. Alberto Calligaro and from the book by Dr. Paolo Mazzarello “La struttura nascosta”, Cisalpino, Istituto Editoriale Universitario – Monduzzi Editore S.p.A, 1996.

For iconographic material on Golgi’s birthplace as well as on Golgi’s life, the contact person is Antonio Stefanini.

First published 20 April 1998

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.