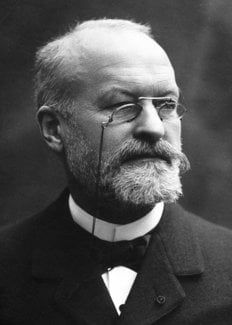

Alphonse Laveran

Biographical

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was born in Paris on June 18, 1845 in the house which was formerly No. 19 rue de l’Est but later became, when this district was rebuilt, an hotel at No. 125, Boulevard St. Michel.

Both his father and paternal grandfather were medical men. His father, Dr. Louis Théodore Laveran, was an army doctor and a Professor at the École de Val-de-Grâce, his mother, née Guénard de la Tour, was the daughter and granddaughter of high-ranking army commanders. When he was very young, Alphonse went with his family to Algeria. His father returned to France as Professor at the École de Val-de-Grâce, of which he became Director with the rank of Army Medical Inspector.

Alphonse, after completing his education in Paris at the Collège Saint Baube and later at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, wished to follow his father’s profession and in 1863 he applied to the Public Health School at Strasbourg, was admitted there and attended the courses for four years. In 1866 he was appointed as a resident medical student in the Strasbourg civil hospitals. In 1867 he submitted a thesis on the regeneration of nerves. In 1870, when the Franco-German war broke out, he was a medical assistant-major and was sent to the army at Metz as ambulance officer. He took part in the battles of Gravelotte and Saint-Privat and in the siege of Metz. After the capitulation of Metz, he went back to France and was attached first to Lille hospital and then to the St. Martin Hospital in Paris. In 1874 he was appointed, after competitive examination, to the Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, previously occupied by his father. In 1878, when his period of office had ended, he was sent to Bône in Algeria and remained there until 1883. It was during this period that he carried out his chief researches on the human malarial parasites, first at Bône and later at Constantine.

In 1882, he went to Rome with the special aim of seeking, in the blood of patients who had become infected with malaria in the Roman Campagna, the parasites he had found in the blood of patients in Algeria. His researches, done at the San Spirito Hospital, confirmed him in the opinion that the blood parasites that he had described were in fact the cause of malaria. His first communications on the malaria parasites were received with much scepticism, but gradually confirmative researches were published by scientists of every country and, in 1889, the Academy of Sciences awarded him the Bréant Prize for his discovery, which was from that time not disputed, of the malarial parasites. In 1884, he was appointed Professor of Military Hygiene at the École de Val-de-Grâce.

In 1894, his period of office as professor having ended, he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the military hospital at Lille and then Director of Health Services of the 11th Army Corps at Nantes. He had neither a Laboratory nor patients, but he wished to continue his scientific investigations. He now held the rank of Principal Medical Officer of the First Class and in 1896 he entered the Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service. From 1897 until 1907, he carried out many original researches on endoglobular Haematozoa and on Sporozoa and Trypanosomes. In 1907 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on protozoa in causing diseases and he gave half the Prize to found the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908 he founded the Société de Pathologie Exotique, over which he presided for 12 years. He did not abandon his interest in malaria. He visited the malarious areas of France (the Vendée, Camargue and Corsica). He was the first to express the view that the malarial parasite must be found, outside the human body, as a parasite of Culicidae and, after this view had been proved by the patient researches of Ronald Ross, he played a large part in the enquiry on the relationships between Anopheles and malaria in the campaign undertaken against endemic disease in swamps, notably in Corsica and Algeria.

Since 1900, he especially studied the trypanosomes and published either independently or in collaboration with others, a large number of papers on these blood parasites. He successively studied: the trypanosomes of the rat, the trypanosomes that cause Nagana and Surra, the trypanosome of horses in Gambia, a trypanosome of cattle in the Transvaal, the trypanosomiases of the Upper Niger, the trypanosomes of birds, Chelonians, Batrachians and Fishes and finally and especially the trypanosome which causes the terrible endemic disease of Equatorial Africa known as sleeping sickness. His work (not completed) on the treatment of trypanosomiases and especially on infections with Tr.gambiense have already had important results.

To sum up, Laveran did not, for 27 years, cease to work on pathogenic Protozoa and the field he opened up by his discovery of the malarial parasites has been increasingly enlarged. Protozoal diseases constitute today one of the most interesting chapters in both medical and veterinary pathology.

Laveran was, in 1893, elected a Member of the Academy of Sciences. He also became, in 1912, a Commander of the Legion of Honour. During the years 1914-1918, he took part in all the committees concerned with the maintenance of the good health of the troops, visiting Army Corps, compiling reports and appropriate instructions. He was a member, associate or honorary member of a vast number of learned societies in France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Rumania, Russia, the U.S.A., the Netherlands Indies, Mexico, Cuba and Brazil.

In 1885 he married Mlle. Pidancet. On May 18, 1922, he died after an illness lasting several months.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.