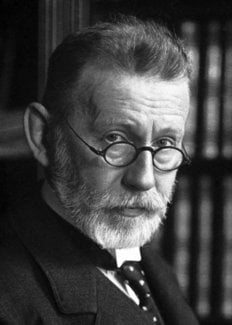

Paul Ehrlich

Biographical

Paul Ehrlich was born on March 14, 1854 at Strehlen, in Upper Silesia*, Germany. He was the son of Ismar Ehrlich and his wife Rosa Weigert, whose nephew was the great bacteriologist Karl Weigert.

Ehrlich was educated at the Gymnasium at Breslau and subsequently at the Universities of Breslau, Strassburg, Freiburg-im-Breisgau and Leipzig. In 1878 he obtained his doctorate of medicine by means of a dissertation on the theory and practice of staining animal tissues. This work was one of the results of his great interest in the aniline dyes discovered by W. H. Perkin in 1853.

In 1878 he was appointed assistant to Professor Frerichs at the Berlin Medical Clinic, who gave him every facility to continue his work with these dyes and the staining of tissues with them. Ehrlich showed that all the dyes used could be classified as being basic, acid or neutral and his work on the staining of granules in blood cells laid the foundations of future work on haematology and the staining of tissues.

In 1882 Ehrlich published his method of staining the tubercle bacillus that Koch had discovered and this method was the basis of the subsequent modifications introduced by Ziehl and Neelson, which are still used today. From it was also derived the Gram method of staining bacteria so much used by modern bacteriologists.

In 1882 Ehrlich became Titular Professor and in 1887 he qualified, as a result of his thesis Das Sauerstoffbedürfnis des Organismus (The need of the organism for oxygen) as a Privatdozent (unpaid lecturer or instructor) in the Faculty of Medicine in the University of Berlin. Later he became an Associate Professor there and Senior House Physician to the Charité Hospital in Berlin.

In 1890 Robert Koch, Director of the newly established Institute for Infectious Diseases, appointed Ehrlich as one of his assistants and Ehrlich then began the immunological studies with which his name will always be associated.

At the end of 1896 an Institute for the control of therapeutic sera was established at Steglitz in Berlin and Ehrlich was appointed its Director. Here he did further important work on immunology, especially on haemolysins. He also showed that the toxin-antitoxin reaction is, as chemical reactions are, accelerated by heat and retarded by cold and that the content of antitoxin in antitoxic sera varied so much for various reasons that it was necessary to establish a standard by which their antitoxin content could be exactly measured. This he accomplished with von Behring‘s antidiphtheritic serum and thus made it possible to standardize this serum in units related to a fixed and invariable standard. The methods of doing this that Ehrlich then established formed the basis of all future standardization of sera. This work and his other immunological studies led Ehrlich to formulate his famous side-chain theory of immunity.

In 1897 Ehrlich was appointed Public Health Officer at Frankfurt-am-Main and when, in 1899, the Royal Institute of Experimental Therapy was established at Frankfurt, Ehrlich became its Director. He also became Director of the Georg Speyerhaus, which was founded by Frau Franziska Speyer and was built next-door to Ehrlich’s Institute. These appointments marked the beginning of the third phase of Ehrlich’s many and varied researches. He now devoted himself to chemotherapy, basing his work on the idea, which had been implicit in his doctorate thesis written when he was a young man, that the chemical constitution of drugs used must be studied in relation to their mode of action and their affinity for the cells of the organisms against which they were directed. His aim was, as he put it, to find chemical substances which have special affinities for pathogenic organisms, to which they would go, as antitoxins go to the toxins to which they are specifically related, and would be, as Ehrlich expressed it, «magic bullets» which would go straight to the organisms at which they were aimed.

To achieve this, Ehrlich tested, with the help of his assistants, hundreds of chemical substances selected from the even larger number of these that he had collected. He studied, among other subjects, the treatment of trypanosomiasis and other protozoal diseases and produced trypan red, which was, as his Japanese assistant Shiga showed, effective against trypanosomes. He also established, with A. Bertheim, the correct structural formula of atoxyl, the efficiency of which against certain experimental trypanosomiases was known. This work opened a way of obtaining numerous new organic compounds with trivalent arsenic which Ehrlich tested.

At this time, the spirochaete that causes syphilis was discovered by Schaudinn and Hoffmann in Berlin, and Ehrlich decided to seek a drug that would be effective especially against this spirochaete. Among the arsenical drugs already tested for other purposes was one, the 606th of the series tested, which had been set aside in 1907 as being ineffective. But when Ehrlich’s former colleague Kitasato sent a pupil of his, named Hata, to work at Ehrlich’s Institute, Ehrlich, learning that Hata had succeeded in infecting rabbits with syphilis, asked him to test this discarded drug on these rabbits. Hata did so and found that it was very effective.

When hundreds of experiments had repeatedly proved its efficacy against syphilis, Ehrlich announced it under the name «Salvarsan». Subsequently, further work on this subject was done and eventually it turned out that the 914th arsenical substance to which the name «Neosalvarsan» was given, was, although its curative effect was less, more easily manufactured and, being more soluble, became more easily administered. Ehrlich had, like so many other discoverers before him, to battle with much opposition before Salvarsan or Neosalvarsan were accepted for the treatment of human syphilis; but ultimately the practical experience prevailed and Ehrlich became famous as one of the main founders of chemotherapy.

During the later years of his life, Ehrlich was concerned with experimental work on tumours and on his view that sarcoma may develop from carcinoma, also on his theory of athreptic immunity to cancer.

The indefatigable industry shown by Ehrlich throughout his life, his kindness and modesty, his lifelong habit of eating little and smoking incessantly 25 strong cigars a day, a box of which he frequently carried under one arm, his invariable insistence on the repeated proof by many experiments of the results he published, and the veneration and devotion shown to him by all his assistants have been vividly described by his former secretary, Martha Marquardt, whose biography of him has given us a detailed picture of his life in Frankfurt. In Frankfurt the street in which his Institute was situated was named Paul Ehrlichstrasse after him, but later, when the Jewish persecution began, this name was removed because Ehrlich was a Jew. After the Second World War, however, when his birth-place, Strehlen, came under the jurisdiction of the Polish authorities, they renamed it Ehrlichstadt, in honour of its great son.

Ehrlich was an ordinary, foreign, corresponding or honorary member of no less than 81 academies and other learned bodies in Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, ltaly, The Netherlands, Norway, Roumania, Russia, Serbia, Sweden, Turkey, the U.S.A. and Venezuela. He held honorary doctorates of the Universities of Chicago, Göttingen, Oxford, Athens and Breslau, and was also honoured by Orders in Germany, Russia, Japan, Spain, Roumania, Serbia, Venezuela, Denmark (Commander Cross of the Danebrog Order), and Norway (Commander Cross of the Royal St. Olaf Order).

In 1887 he received the Tiedemann Prize of the Senckenberg Naturforschende Gesellschaft at Frankfurt/Main, in 1906 the Prize of Honour at the XVth International Congress of Medicine at Lisbon, in 1911 the Liebig Medal of the German Chemical Society, and in 1914 the Cameron Prize of Edinburgh. In 1908 he shared with Metchnikoff the highest scientific distinction, the Nobel Prize.

The Prussian Government elected him Privy Medical Counsel in 1897, promoted him to a higher rank of this Counsel in 1907 and, in 1911, raised him to the highest rank, Real Privy Counsel with the title of Excellency.

Ehrlich married, in 1883, Hedwig Pinkus, who was then aged 19. They had two daughters, Stephanie (Mrs. Ernst Schwerin) and Marianne (Mrs. Edmund Landau).

When the First World War broke out in 1914 he was much distressed by it and at Christmas of that year he had a slight stroke. He recovered quickly from this, but his health which had never, apart from a tuberculous infection in early life which had made it necessary for him to spend two years in Egypt, failed him, now began to decline and when, in 1915, he went to Bad Homburg for a holiday, he had, on August 20 of that year, a second stroke which ended his life.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.