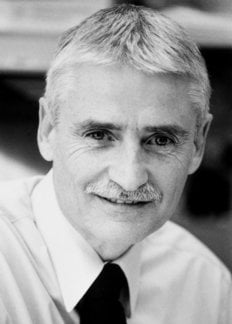

Leland Hartwell

Biographical

I don’t remember much about my early childhood. I am told that before I began school, my older cousin would return from her school and teach me what she had learned. By the time I was 10 or so, I was displaying a curiosity that might have suggested an academic bent. I was an avid collector of bugs, butterflies, lizards, snakes, and spiders. I remember on one of these adventures learning to be skeptical of everything one reads in books. I had read that lizards do not have teeth. I had grabbed a very big lizard and stared in disbelief as it turned its head, displayed a fine set of teeth and sank them into my thumb. From age 13 to 17 I was preoccupied with sports, girls and cars. But midway through high school a fortunate event happened. I became unhappy with the football coach and bored of carousing with my car club friends. A close friend of mine suggested we transfer to the cross town high school and my accommodating mother moved apartments so I could do so. At the new school I was fortunate to find some teachers that challenged me, particularly a physics teacher and my grades improved dramatically. Since no one in my family had ever been to college, I had little in the way of career guidance. However, I was good at math and physics and I liked mechanical drawing, so I thought I might become an engineer. I went for one year to a two-year junior college, Glendale Junior College, in preparation, taking math, chemistry and physics. I did well, and my counselor encouraged me to meet with a recruiter from the California Institute of Technology. This was my next major break. I took the entrance exams and was admitted into the sophomore class.

For the first time, I was in an environment of real science and it was magical. In hindsight, I can see that I was destined for science. I have always been curious and wanted to understand things at a fundamental level. For example, I used to get annoyed at my father, a neon sign man, because he would not explain to me, how neon signs work. I only realized later, that I wanted to know about electricity and atomic emissions, topics that he knew nothing about. At Cal Tech, I enrolled as a physics major. During my sophomore year, I took a lecture course in Biology, taught by James Bonner. He was incredibly enthusiastic. This must have been around 1958, only five years after the discovery of the DNA structure, and the course was all about DNA, RNA and protein. The clincher for me was an optional evening laboratory in bacteriophage genetics taught by Bob Edgar and Charlie Steinberg. Here, I learned that biology could be quantitative and it was little time before I changed my major to biology. At Cal Tech I was able to do research nearly every quarter and summer, in chemistry, biochemistry, and genetics. I worked with Hildegard Lamfrom, Howard Temin and Bob Edgar. Another feature of the Cal Tech undergraduate education was the opportunity to take credits as reading which I did most quarters, reading the original literature in phage genetics and gene regulation.

I graduated in 1961 and went to MIT for graduate school. I had decided that I wanted to work on gene regulation and I knew of only two prominent labs in the US, Arthur Pardee at Berkeley, and Boris Magasanik, at MIT. I visited Arthur Pardee at Berkeley and he was not encouraging so I went to MIT. Being a graduate student at MIT was great fun and very intense. Boris Magasanik would come through the lab each afternoon and stop at each desk to discuss the previous day’s results. I wanted a new result each day so that set quite a pace! I was there only about two and a half years when Boris came to me and said that I had essentially finished my thesis but since no one could leave that soon I would have to stay another year.

By this time François Jacob and Jacques Monod had published their famous work on the lac operon and I figured that gene regulation was pretty well understood. I thought it appropriate to do my postdoctoral work on something much less well understood and I decided to work on the control of cell growth. Going to the literature again, I was most impressed with the work coming out of Renato Dulbecco‘s laboratory, so I applied to Renato and he accepted me. My timing was excellent because Renato was moving to the Salk Institute but the buildings had not been built. We were quartered in temporary buildings that kept the lab groups very small. Most of the original fellows at the Salk had only one or two postdocs so it was very intimate. I spent a lot of time talking with Marguerite Vogt, Renato’s long time collaborator. Marguerite’s enthusiasm for cancer research and her adeptness at cell culture were a joy to behold and try to learn from. During that period I spent about half my time working on polyoma virus infected cells, the main research program of the laboratory, and about half the time trying to get something of my own started. The polyoma work went very well. DNA hybridization was a relatively new technique and Nada Ledinko had come to Renato’s lab with experience with this technique. We used it to show that polyoma infected cells induced cellular DNA synthesis and a complement of cellular DNA replication enzymes. This seemed like it might be fundamentally interesting to the cancer problem. However, none of the three projects that I worked on as possible starting points for my own entry into research worked. I left the lab after only about 18 months as a postdoc, taking a position as assistant professor at the new University of California, Irvine in 1965.

I had applied for and gotten a grant to study the control of cellular DNA synthesis but I was not enthusiastic about the prospects for reaching fundamental insights with mammalian cells. It was again a fortunate circumstance. While I was waiting for my newly ordered equipment to arrive, I spent considerable time in the library trying to figure out what to do. Dan Wulff, another new recruit, suggested that I find a model eukaryotic cell that could be used for genetic studies of cell growth. I thought this a great idea and went to the library to discover that Saccharomyces cerevisiae, baker’s yeast was one of the only singled celled eukaryotic organisms with facile genetics. I visited Bob Mortimer at Berkeley and Herschel Roman and Don Hawthorne at Seattle to find out how one worked with yeast. They were both incredibly kind and generous. Hersch and Don loaned me a micromanipulator to start my work.

I began by isolating temperature-sensitive mutants and analyzing them for macromolecule synthesis and cell division at the restrictive temperature. This approach came directly from my earlier experience with Bob Edgar at Cal Tech where I had seen the power of conditional mutants to analyze phage morphogenesis. Three years later, Herschel Roman invited me to join the faculty at the genetics department in Seattle which I did. Soon after that move, we discovered the power of time-lapse photomicroscopy to study the cell cycle.

Looking back over my life, I feel in some sense destined because of my native interest in understanding things at a fundamental level. And I also feel extremely fortunate for a great number of people who intervened or mentored me on my path. I sought a rigorous approach to mysterious problems and found people at each step that pointed the way. I feel very fortunate to have become a biologist at a time when curiosity was paramount and to have been trained by people who had high standards.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.