Award ceremony speech

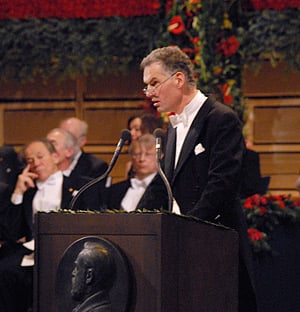

Presentation Speech by Professor Jan Andersson, Member of the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, Member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, 10 December 2008

|

| Professor Jan Andersson delivering the Presentation Speech for the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine at the Stockholm Concert Hall. Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2008 Photo: Hans Mehlin |

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine rewards two discoveries of viruses that cause severe global diseases.

Human history has been subjected to and shaped by major epidemics, such as bubonic plague, cholera, tuberculosis, smallpox, measles and influenza. These communicable diseases have contributed to the downfall of peoples and cultures. They recognise no national boundaries, and when they first appear among a group of people they are often fatal. All new epidemics have generated anxiety and panic reactions due to uncertainty about how the infectious agent spreads. Our foremost antidote is and has been – knowledge.

One part of this year’s Prize goes to Harald zur Hausen, who sought to understand what causes cervical cancer, the world’s second most common cancer among women. Half a million are affected every year. When zur Hausen asserted that human papilloma virus – which was known to induce skin warts – caused this cancer, not many people believed him. He predicted that the virus existed in different types and changed shape in tumour cells. He realised that no virus was formed there, but that certain virus genes instead integrated into cervical cell genomes, thereby giving rise to the cancer over time.

It was not possible to culture the virus, but zur Hausen instead had to prove his hypothesis by using small bits of single-stranded DNA from the actual wart viruses. He used these bits of DNA as bait to be able to attract virus DNA copies, first from genital warts and later also from cervical cancer cells. After more than a decade of persistent work, he isolated different types of human papilloma virus that caused more than 70 per cent of all cervical cancer. Virus genes were present in the DNA of every cancer cell and re-programmed the cells to grow uncontrollably.

This discovery has led to vaccines against these viruses which provide protection against these infections. It has also lead to improved methods for predicting which women are in the risk zone.

The other part of this year’s Prize is related to the discovery of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In 1981 there were a number of alarming reports that young, previously healthy people were dying of pneumonia or unusual tumours. This was the beginning of an epidemic whose enigmatic nature and impact on different cultures defied all previously described epidemics. It started during an era when we thought we had conquered all major infectious diseases. There were now antibiotics, vaccines, good hygiene and improved living conditions that would keep us immune. Institutes for infectious disease control would be shut down. But with everyone talking about AIDS, new concerns spread in many countries.

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier speculated that AIDS was caused by an unknown retrovirus, a kind of tumour virus from the animal kingdom that had more recently also been found in humans. But how could a virus with a size of one ten thousandth of a millimetre trigger all these different manifestations of disease?

Barré-Sinoussi and Montagnier discovered HIV in the lymph nodes of recently infected patients. It was being produced in large quantities in white blood cells and it induced the death of cells of a kind that was missing in patients suffering from AIDS. HIV was like a chameleon. Each patient carried a unique virus variant, which could hide in the host cell genome. Barré-Sinoussi and Montagnier’s discovery explained the progression of the disease and its communicability, enabling them to establish the connection between HIV and AIDS. Methods for discovering infected people and blood products were developed, and HIV/AIDS patients quickly gained access to effective anti-retroviral drugs that helped suppress their disease. So far 60 million people in the world have been infected with HIV, and a total of 25 million have died of AIDS. A growing number of people are receiving anti-retroviral drugs, even in developing countries. Another cause for celebration is that the epidemic is now declining among young people in the countries where it began. However, the best prophylactic against HIV/AIDS is and remains true love, generating longstanding relationships.

Sehr geehrter Herr Professor zur Hausen!

Ihre Entdeckung hat zu der Erkenntnis geführt, daß Viren bei Menschen Krebs erregen können, und daß wir neue Möglichkeiten zur Vorbeugung von Krebs gefunden haben, der durch humane Papillomaviren hervorgerufen wird.

Professeurs Barré-Sinoussi et Montagnier!

Votre découverte nous a révélé l’existence d’un nouveau virus, le VIH, et cette connaissance a ouvert la voie à de nouveaux traitements contre la maladie du VIH/SIDA.

On behalf of the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet it is my privilege and pleasure to express our warmest congratulations and our deepest admiration as I now ask you to step forward to receive the Nobel Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.