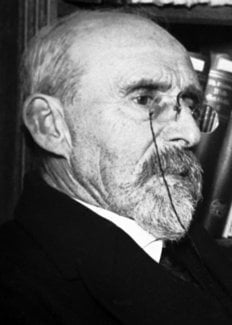

Ferdinand Buisson

Biographical

Ferdinand Édouard Buisson (December 20, 1841-February 16, 1932), «the world’s most persistent pacifist», was born in Paris, the son of a Protestant judge of the St.-Étienne Tribunal. For his ardent partisanship of pacifist, Radical-Socialist, anticlerical views he was vilified by journalists, attacked by clerics and conservative scholars, forced from public office by political slander, and even, at the age of eighty-seven, severely caned by a group of student protesters who disrupted a pacifist meeting at which he was speaking. A progressive educator, he played a vital role in the modernization of French primary education.

Buisson attended the Collège d’Argentan and the Lycée St.-Étienne but left school at the age of sixteen to help support the family when his father died. He completed his secondary education at the Lycée Condorcet and his undergraduate degree at the University of Paris, obtained an advanced degree and certification to teach philosophy, and much later, at the age of fifty-one, took his doctorate in literature.

In 1866, unwilling to swear allegiance to the Emperor and consequently unable to find a teaching post, he became an expatriate in Switzerland where he taught at the Académie de Neuchâtel. The following year he participated in the Geneva peace congress which founded the Ligue internationale de la paix et de la liberté. Among his writings during this period of exile are L’Abolition de la guerre par l’instruction [Abolishing War through Education], published in États-Unis de l’Europe, and revisions of his Christianisme libéral [Liberal Christianity], which develops the concept of a liberal faith in which organized religion is supplanted by a personal morality independently arrived at.

Returning to France after the defeat of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian War, Buisson began his career as an educational administrator. He was named an inspector of primary education in Paris by Jules Simon, the minister for education in the Third Republic, but because of his speeches and pamphlets pleading for a system of secular education, he was accused in the National Assembly of disrespect for the Bible and in the general outcry that ensued felt called upon to resign. Later he became secretary of the Statistical Commission on Primary Education, attended the Vienna and the Philadelphia Expositions as a delegate of the Ministry of Public Instruction, and prepared extensive reports on education in Austria and the United States. In August of 1878, Jules Ferry, who had been appointed minister for education, gave Buisson the post of inspector general of primary education in France and, in the following year, that of director of primary education, a position he held for the next seventeen years. During the 1880’s he collaborated with Ferry in drafting laws establishing free, compulsory, secular primary education in France, defended them in hard-fought legislative battles in the Chamber of Deputies, and finally participated in their implementation.

Buisson was scholar as well as administrator. In 1878 he edited and saw through publication the first volume of the four-volume work Dictionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. In 1896 he became editor-in-chief of an influential journal of education, Manuel général d’instruction primaire. From 1896 to 1902 he was professor of education at the Sorbonne.

The Dreyfus Affair ignited Buisson’s desire to enter politics. Among the first of the ardent Dreyfusards when that affair exploded, he undertook a vehement writing and speaking campaign to reverse the Dreyfus decision and helped to found the League of the Rights of Man (1898) which grew out of the Dreyfus case and of which he became president in 1913. From 1902 to 1914 he was the elected deputy for the Seine. A Radical-Socialist, he supported compulsory, secular schooling; served as chairman of a commission on the issue of separation of church and state and as vice-chairman of a commission on proposals for social welfare legislation; sat on the Commission for Universal Suffrage where he upheld the vote for women and supported the principle of proportional representation.

Buisson returned to the Chamber in 1919. He criticized the Treaty of Versailles in an open letter dated May 23, 1919, but in other publications and in speeches endorsed the League of Nations as a practical instrument in the effort to achieve international peace. Hoping to unite leftist groups, rejuvenate the radical party, and win support for his educational policies, he formed the League of the Republic in 1921. The new organization did not prevent his defeat in the election of 1924, however, and Buisson, now eighty-three, retired to Thieuloy-Saint-Antoine in Oise. There he became a municipal councillor and even tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain Radical-Socialist backing for the regional Senate seat.

Nor did he allow his work for peace to languish. A partisan of a peaceful détente between France and Germany, he made a speaking tour of Germany to encourage reconciliation between the two countries. And the proceeds of the Nobel Peace Prize he donated to various pacifist programs.

At the age of ninety-one, Buisson died of heart disease at his home in Thieuloy-Saint-Antone, survived by two sons and a daughter.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Basch, Victor, «Ferdinand Buisson», in Les Cahiers des droits de l’homme (January 20, 1925). |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Le Christianisme libéral. Paris, Cherbuliez, 1865. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Le Colonel Picquart en prison: Discours prononcé le 10 mai 1899. Paris, Ollendorff, 1899. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Constitution immédiate de la Société des Nations. Paris, Ligue, des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, [1908]. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, éd., Diaionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. 4 Tomes. Paris, Hachette, 1878-1887. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Foi laïque: Extraits de discours et d’écrits, 1878-1911. Paris, Hachette, 1912. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Politique radicale: Étude sur les doctrines du parti radical et radical-socialiste. Paris, Giard et Brière, 1908. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Rapport sur l’instruction primaire à l’Exposition universelle de Philadelphie en 1876. Paris, Impr. nationale, 1878. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Rapport sur l’instruction primaire à l’Exposition universelle de Vienne en 1873. Paris, Impr. rationale, 1875. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Réligion, la morale et la science, et leur conflit dans l’éducation contemporaine: Quatre conférences faites à l’aula de l’Université de Genève (avril, 1900). Paris, Fischbacher, 1900. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, and Frederic E. Farrington, eds., French Educational Ideals of Today: An Anthology of the Molders of French Educational Thought of the Present. Yonkers-on-Hudson, N.Y., World, 1919. |

| Talbott, John E., The Politics of Educational Reform in France, 1918-1940. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1969. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.