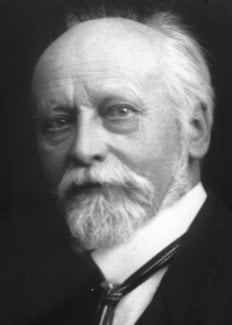

Ludwig Quidde

Biographical

Ludwig Quidde (March 23, 1858 – March 4, 1941), the oldest son of a wealthy merchant, grew up in the republican atmosphere of the Hanseatic city of Bremen, enjoying an unusually liberal education at its humanistic gymnasium, «an education in freedom to freedom»1. He studied at the Universities of Strassburg and Göttingen, where his professors recognized and furthered his aptitude for historical research. Under the sponsorship of Professor Weizsäcker in Göttingen, Quidde was given a post on a board of editors responsible for the publication of the medieval German Reichstag documents, a post he held until 1933 when the Bavarian Historical Commission removed him for political reasons. In 1889 he founded the Deutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft [German Review of Historical Sciences], a journal which he edited until 1896; from 1890 to 1892, he was on the staff of the Prussian Historical Institute in Rome. Quidde, however, did not follow a career as a professional historian, perhaps because he had a substantial private fortune, but he always maintained a lively interest in history, especially constitutional history, even after his attention had turned from the academic to the political.

The publication of the pamphlet Caligula: A Study of Imperial Insanity2 in 1894 changed the course of Quidde’s career. Seemingly an objective study of the Roman emperor Caligula, emphasizing his madness, his pleasure in sham heroics, his ruthless use of power, his vanity as an actor and conceit as an orator, the pamphlet was, in fact, a satire on Emperor Wilhelm II and the «Byzantine» nature of the Prussian society of which he was a part. Quidde escaped conviction of the charge of lese majesty: he denied that he had intended to draw an analogy between the two emperors, thus leaving to the prosecution the task of proving the validity of the analogy, an alternative too embarrassing to accept.

Quidde entered politics in Munich. In 1895 he helped to reorganize the German People’s Party which was, in political philosophy, anti-prussian and antimilitary; in 1902 he won a seat on the City Council of Munich; from 1907 to 1919 he served in the Bavarian Assembly; in 1919 he was elected to the Weimar National Assembly.

Quidde’s political ideology was a direct heritage from the Enlightenment. Uncompromisingly ethical, he strove to imbue the German people with a sense of justice which would of itself generate social reform. He had the courage of his convictions. After delivering a political speech on January 20, 1896, Quidde was accused of lese majesty, tried, and sentenced to three months in the Munich prison Stadelheim. For writing an article in 1924 attacking secret military training, he was arrested, found guilty of «collaborating with the enemy», and put in prison for a brief period.

Initially not antiwar on principle, Quidde’s interest in the peace movement, prompting him to join the German Peace Society shortly after its founding in 1892, grew out of his historical studies, his ethical ideals, his distrust of the military, and the urgings of his wife, Margarethe, whom he married in 1882. He filled a position on the Council of the International Peace Bureau in Bern, rose to a position of leadership in the World Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901, joined with Frédéric Passy at the Congress at Lucerne in 1905 to achieve a rapprochement between German and French, supervised the organization of the World Peace Congress of 1907 in Munich, became president of the German Peace Society in 1914, a position he held for fifteen years.

When World War I broke out, Quidde went to The Hague, attempting to maintain ties with English and French peace groups. The attempt failed, and when Quidde returned to Germany he was charged with treason, though the charges were later dropped. Nonetheless, Quidde was kept under surveillance for months, his mail censored, and his pamphlets confiscated. At the end of the war, Quidde continued to pull together the remnants of the German peace movement, heading the German Peace Cartel, a body composed of twenty-one organizations.

When Hitler came to power, Quidde fled first to Munich and then to Geneva, where he lived from March, 1933, until his death in March, 1941. Although Quidde’s private fortune had been wiped out by the inflation, he was able to live fairly well with the help of friends and with a subvention from the Nobel Peace Prize Committee for his projected book, German Pacifism during the World War, which was never finished. Even in exile, Quidde continued to attend World Peace Congresses, to publish articles, and to exercise his organizational talents by founding the Comité de secours aux pacifistes exilés to care for fellow political exiles from Nazi Germany.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Quidde, Ludwig, Caligula: Eine Studie über römischen Cäsarenwahnsinn. Leipzig, Wilhelm Friedrich, 1894. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, Der erste Schritt zur Weltabrüstung. Berlin, Hensel, 1927. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, «European Militarism before the War», in World Tomorrow, 9 (October, 1926) 161-162. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, «The Future of Germany», in Living Age, 321 (April 5, 1924) 635-638. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, «Recollections of a Stutterer», in Living Age, 328 (February 13, 1926) 360-363. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, Die Schuldfrage. Berlin, Schwetschke, 1922. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, «Shall There Be a Germany Irredenta?», in Living Age, 302 (September 6, 1919) 583-585. |

| Quidde, Ludwig, «Sollen wir annektieren?» Denkschrift des Bundes Neues Vaterland. (Anonym) Berlin, 1915. |

| Taube, Utz-Friedebert, Ludwig Quidde: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des demokratischen Gedankens in Deutschland. Kallmünz über Regensburg, Lassleben, 1963. Contains complete bibliographies: of Quidde’s articles and pamphlets, pp. 188-201; of all articles for and against Quidde’s Caligula, pp. 201-203; of secondary materials, pp. 203-216. |

| Wehberg, Hans, ed., Ludwig Quidde: Ein deutscher Demokrat und Vorkämpfer der Völkersverständigung. Offenbach am Main, Bollwerk, 1948. |

Editor’s Note

In a subsequent annotation in Europäische Gespräche (Heft VI, Juni 1931, S. 304) – found when this volume was already in galley proof – Quidde comments further on his interpretation of the draft resolution of March 22. His interpretation is incomplete, he says, because it does not mention the draft’s «unreserved recognition of the principle of balance between victor and defeated of 1918 in the question of armaments». It is inaccurate, he continues, because it implies that restrictions of individual elements of armaments should proceed only from suggestions made in the Peace Treaties; whereas, in fact, the draft demands the prohibition of the specific means of war forbidden by the Peace Treaties and recommends the adoption of budgetary restrictions as a method of limiting the remaining means of war – a method not mentioned in the treaties.

1. Ludwig Quidde, Schuldisziplin und Elternhaus (Munich: 1911), p. 17.

2. Caligula might have gone unnoticed but for a short article in the Kreuzzeitung, May 18, 1894, which made explicit the parallels between Caligula and Wilhelm II which Quidde had only implied.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.