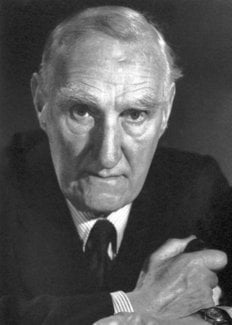

Lord Boyd Orr

Biographical

John Boyd Orr (September 23, 1880-June 25, 1971) was born in Kilmaurs, Ayrshire, Scotland. His father, R.C. Orr, was a pious and intelligent man whose sudden enthusiasms led to frequent reversals of fortune, but, although his finances were often depleted, he and his wife and their seven children enjoyed a pleasant life in their rural community. Having begun his education in the village school, John at the age of thirteen was sent to Kilmarnock Academy, twenty miles away, but he was more interested in the life of the navvies and quarrymen who worked in his father’s quarry than in his education and so was returned to the village school. There he became a member of the staff as a «pupil teacher», earning £20 a year by the time he was eighteen.

Aided by scholarships, he was able to attend simultaneously a teachers’ training college and Glasgow University. Of these student days he says in his autobiography that he worked hard in the arts curriculum but that his most vivid recollections are of the sights and sounds of the old Glasgow slums which he would prowl on Saturday nights1.

Finding the three years he spent teaching in a secondary school neither financially profitable nor intellectually satisfying, he returned to Glasgow University in 1905, enrolling for a degree in medicine and for one in the biological sciences. Degrees in hand in record time, he served as a ship’s surgeon for four months and for six weeks as a replacement for a vacationing doctor, but he forsook the practice of medicine for research, accepting a two-year Carnegie research fellowship in physiology.

On April 1, 1914, Dr. Boyd Orr arrived in Aberdeen to assume direction of the Nutrition Institute, only to be told that there was no Institute in reality, only an approved scheme of research. Within a month, Boyd Orr had drawn up plans for an impressive research facility, too impressive, indeed, to be financed. The compromise he made is symbolic of the nature of the man: he was willing to delay the building of the total structure provided that the first wing be made of granite, not of wood as originally suggested.

His work was interrupted by World War I during which he served first in the Royal Army Medical Corps, earning two decorations for bravery in action, then in the Royal Navy, and finally, simultaneously in both, for he was loaned by the Navy to the Army to do research in military dietetics.

After the war Boyd Orr returned to the Institute and in the next decade or so, put to work a hitherto unsuspected talent for money raising. The first new building of Rowett Research Institute – the name now given to the Institute in honor of a major donor – was dedicated by Queen Mary in 1922; there followed the Walter Reid Library in 1923-1924, the thousand-acre John Duthie Webster Experimental Farm in 1925, Strathcona House, to accommodate research workers and visiting scientists, in 1930. In 1931 he founded and became editor of Nutrition Abstracts and Reviews.

Time-consuming as his various administrative duties were, he was still able to direct fundamental research in nutrition, primarily in animal nutrition in these early days of the Institute. His influential Minerals in Pastures and Their Relation to Animal Nutrition (1929) was published in this period. During the 1930’s, however, after extensive experiments with milk in the diet of mothers, children, and the underprivileged, and after large-scale surveys of nutritional problems in many nations throughout the world, Boyd Orr’s interests swung to human nutrition, not only as a researcher but also as a propagandist for healthful diets for all peoples everywhere. His report of 1936, Food, Health and Income, revealed the «appalling amount of malnutrition» among the people of Great Britain regardless of economic status2 and became the basis for the later British policy on food during World War II, which he helped to formulate as a member of Churchill‘s Scientific Committee on Food Policy.

At war’s end, Boyd Orr, aged sixty-five, retired from Rowett Institute, but accepted three new positions: a three-year term as rector of Glasgow University, a seat in the Commons representing the Scottish universities, and the post of director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Boyd Orr found his work with the FAO exasperating because of the FAO’s lack of authority and funds, but he energetically pursued every avenue for improving the world production and equitable distribution of food. In 1946, under the aegis of the FAO, he set up an International Emergency Food Council, with thirty-four member nations, to meet the postwar food crisis. He traveled extensively throughout the world trying to get support for a comprehensive food plan and was bitterly disappointed when his proposal for the establishment of a World Food Board failed in 1947 when neither Britain nor the United States would vote for it.

Believing that the FAO could not, at that point, become a spearhead for a movement to achieve world unity and peace, Boyd Orr resolved to resign as director-general and to go into business. Within three years he earned a bigger net income from directorships than he had ever had from scientific research, and with capital gains made on the Stock Exchange, he established a comfortable personal estate. It was symbolic of this period of his life that he should have been informed of his Nobel Peace Prize award by his banker. The prize money, however, he donated to the National Peace Council, the World Movement for World Federal Government, and various other such organizations.

In the years following the Second World War, Boyd Orr was associated with virtually every organization that has agitated for world government, in many instances devoting his considerable administrative and propagandistic skills to the cause.«The most important question today», he says in his autobiography, «is whether man has attained the wisdom to adjust the old systems to suit the new powers of science and to realize that we are now one world in which all nations will ultimately share the same fate. »3

John Boyd Orr, himself a scientist-adjuster of old systems, died at his home in Scotland in June, 1971, at the age of ninety.

Selected Bibliography

Boyd Orr, Lord John, As I Recall, with an Introduction by Ritchie Calder. London, MacGibbon & Kee, 1966.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, Fighting for What? London, Macmillan, 1942.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, Food and the People. London, Pilot Press, 1943.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, Food, Health and Income. London, Macmillan, 1936.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, Food: The Foundation of World Unity. London, National Peace Council, 1948.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, International Liaison Committee of Organisations for Peace: A New Strategy of Peace. London, National Peace Council, 1950.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, Minerals in Pastures and Their Relation to Animal Nutrition. London, Lewis, 1929.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, The National Food Supply and Its Influence on National Health. London, King, 1934.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, «Nutritional Science and State Planning», in What Science Stands For, ed. by John Boyd Orr et al. London, Allen & Unwin, 1937.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, The White Man’s Dilemma: Food and the Future. With the cooperation of David Lubbock. London, Allen & Unwin, 1953. (2nd ea., 1964.)

Boyd Orr, Lord John, The Wonderful World of Food: The Substance of Life. Garden City, N.Y., Garden City Books, 1958.

Boyd Orr, Lord John, and David Lubbock, Feeding the People in Wartime. London, Macmillan, 1940.

Calder, Ritchie, «The Man and his Message», in Food for a Hungry World, a special issue of Survey Graphic, 37 (March, 1948) 99-104.

Current Biography, 7 (1946). New York, Wilson.

Hambidge, Gove, The Story of FAO. New York, Van Nostrand, 1955.

Vries, Eva de, Life and Work of Sir John Boyd Orr. Wageningen, The Netherlands, Veenman, 1948.

1. John Boyd Orr, As I Recall, p. 42.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.