Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

Nobel Prize lecture

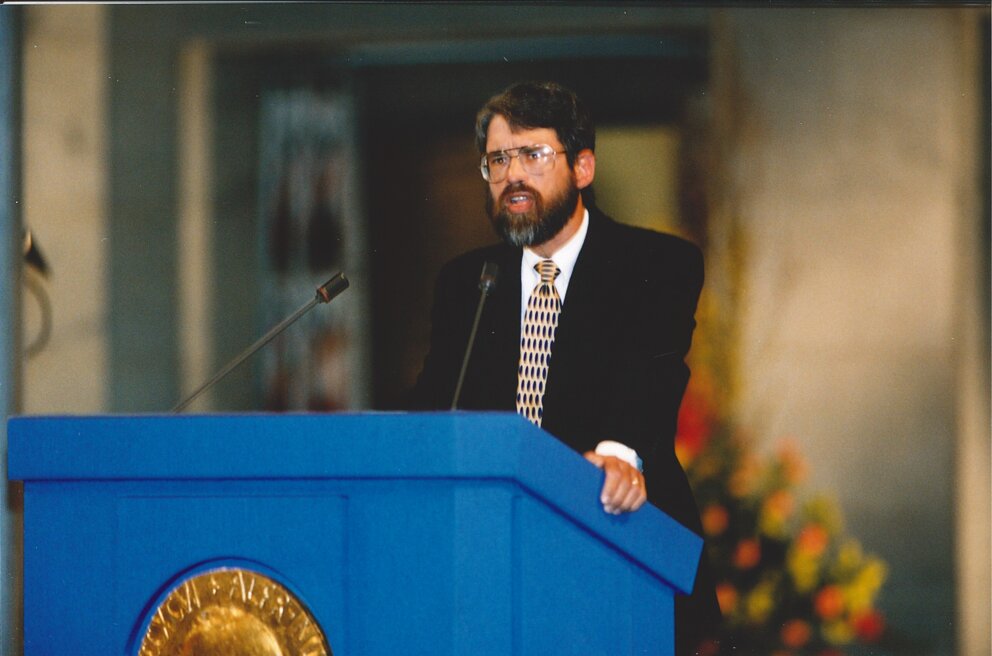

John P. Holdren delivering the Nobel Lecture.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Nobel Lecture by John P. Holdren, Chair of the Executive Committee of the Pugwash Council

Arms Limitation and Peace Building in the Post-Cold-War World

Your Majesties, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen:

It is a special privilege for me, as Chair of the Executive Committee of the Pugwash Council, to present this lecture on behalf of the Pugwash Conferences on the occasion of our organization’s sharing the Nobel Peace Prize with our founder and President, Professor Joseph Rotblat. The award to the Pugwash Conferences is the highest form of recognition for the efforts, on behalf of arms reductions and peace building, of all of the thousands of scientists and public figures, from more than 100 countries, who have taken part in Pugwash activities since the first meeting in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, nearly 40 years ago. I am sure I speak for all these Pugwash participants, not just for the Pugwash Council, in thanking the Norwegian Nobel Committee for this high honor to our organization and our founder.

I am sure, also, that all of us regard this prize less as a reward for past efforts on behalf of peace than as encouragement and reinforcement for the continuing efforts that are still required – from Pugwash, from the many other non-governmental organizations committed to building peace and international cooperation, from governments, and, indeed, from every individual who cares about the future of our civilization. It is mainly on the nature and scope of this continuing need that I wish to focus my comments, on behalf of the Pugwash Conferences, this afternoon. In composing these thoughts, I have drawn heavily on the suggestions of many members of the Pugwash Council, as well as on recent statements and declarations issued by the Council collectively on these topics.

The long dark night of the Cold War has finally passed, and with its passing the peril of a global thermonuclear conflagration has substantially receded. This alleviation of the nuclear danger is unquestionably a great blessing and a proper cause for celebration. But it is not, as so many seem to be supposing, a cause for either self-congratulation or complacency. Those who are congratulating themselves for the role they played in this narrow escape – the hawks, who believe that potent deterrent forces and frequent saber-rattling kept the nuclear peace, and the doves, who believe that candid communication and negotiated arms-control agreements made the difference – are all probably underestimating the extent to which good luck, more than clear-eyed leadership or sensible restraint, allowed the superpowers to careen for forty years along the edge of the nuclear chasm without falling in. And those who complacently believe that the danger of nuclear destruction is now completely under control have simply not surveyed the new landscape of insecurity that the post-Cold-War dawn has revealed.

The troublesome features of this landscape that must now command our attention are at least six in number:

* First are the dangers posed by the tens of thousands of nuclear weapons that are still deployed at various stages of readiness for use – primarily in the United States and Russia but also, with numbers in the hundreds, in the “intermediate” and undeclared nuclear-weapon states. Contrary to public perceptions, it is still all too possible that these nuclear weapons could be used, in greater or lesser numbers, as a result of various combinations of crisis conditions, electronic and mechanical malfunctions, breaks in the chain of official command and control, and human errors, misjudgments, or misguided impulses.

* Second is the danger that the psychological residues of the Cold War mentality, if allowed free rein, could bring a halt to the progress in arms reductions that has been underway and could lead, ultimately, to the renewal of increasingly expensive and risky military competitions and confrontations between Russia and the West, even in the absence of the former Cold War’s ideological basis. The reality of this peril is apparent in the failure of the United States and Russia, until now, to ratify either the START 2 agreement or the Chemical Weapons Convention,1 as well as in the very serious possibility that the United States will choose to abandon the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty – the cornerstone of nuclear arms limitation for nearly a quarter century – in order to pursue the illusion of a national defense against ballistic missiles.

* Third are the dangers of further proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons capabilities into the possession of more and more nations. This problem may actually have been aggravated by the end of the Cold War, which increased ambiguities about the regional security interests and commitments of the major nuclear-weapon states. The proliferation problem will certainly be aggravated if the existing nuclear-weapon states continue, now that the Cold War is over, to act as if their possession of nuclear weapons still confers crucial security benefits which they intend to keep indefinitely, contrary to their obligations under the recently extended Non-Proliferation Treaty.

* Fourth is the set of difficulties and dangers, both physical and political, posed by the specific stocks of nuclear and chemical weapons made surplus by the end of the Cold War and the accompanying arms-control agreements. These problems entail, on the physical side, the safe storage and dismantlement of these surplus weapons and the disposition of their active ingredients in ways that convincingly preclude their re-use for military purposes. Undue delay in these endeavors will not only prolong the risk of re-incorporation of these weapons and weapon ingredients into the national arsenals from which they came, or into other national or sub-national arsenals by way of sale or theft; it also will produce a problem of political perceptions about whether the countries that own these weapons and materials really intend to get rid of them at all; such perceptions would be an obstacle both to further arms reductions and to non-proliferation.

* The fifth set of problems in the post-Cold-War security landscape has to do with the dangers and destruction engendered by local armed conflicts, actual and incipient, arising from all of the traditional causes of war: religious and ethnic hatreds, disputes over territory and resources, the tensions of emergent statehood, the aspirations of power-hungry dictators, and the stresses of frustrated economic aspirations. Such conflicts occurred throughout the Cold War, of course, as well as before; but, like the proliferation dangers already mentioned, they may have become even more dangerous in its aftermath. Confined in geographic scope but not in ferocity or in the indiscriminate killing of noncombatants, these wars have been fueled in many cases by vast flows of conventional weaponry from armories built up to service the Cold War, as well as by emergent indigenous arms industries in the South; they have already seen the use of chemical weapons in some instances, and are likely to see wider use of weapons of mass destruction in the future; and the extant array of regional and global security institutions seems almost powerless to prevent or contain them.

* Last in my order of presentation of the security issues that deserve our attention in the post-Cold-War world, although by no means last in importance, is the set of interactions linking security, economic development, and environment. It should be obvious that a durable global peace cannot be attained in a world in which a substantial fraction of the population languishes in poverty. There can be no lasting security, even for the rich, in a world full of discontented poor. It is perhaps less obvious, but no less true, that the durable and pervasive prosperity so essential to durable peace depends as much on environmental conditions and processes as on economics ones. Yet current practices in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, energy supply, and manufacturing are clearly eroding the environmental underpinnings of prosperity worldwide, and the combination of population growth and rising consumption per person is increasing the pressure on environmental resources much faster than technological improvements, at current level of effort, can abate it. There is simply no sign of the levels of investment and cooperation in environmentally sustainable development that would be required to achieve a durable prosperity for everyone in today’s world of nearly 6 billion people – not to mention tomorrow’s world of 9 or 10 billion. Persisting in this oversight is a prescription for a degree of misery, social and political instability, and conflict in the twenty-first century that no amount of effort at arms control and crisis management will be able to contain.

Although the Pugwash Conferences came into being, four decades ago, in response to the extraordinary dangers posed by thermonuclear weapons, and while the pursuit of ways to reduce those dangers has always remained at the core of Pugwash concerns, our founders recognized from the outset the seamlessness of the web of interconnections linking the nuclear danger with the dangers of other weapons of mass destruction, with conventional conflicts, and with the ultimate causes of war rooted in the human condition. Thus the Pugwash agenda expanded, in the early years of the organization, to embrace not only the perils of nuclear weapons but also those aspects of the wider security landspace in which the Pugwash format – natural scientists meeting with other scholars and with political and military figures for off-the-record exploration of the issues – might be able to make a contribution.

That Pugwash was constituted from the beginning not solely along bilateral lines but rather with much broader participation was a great asset in dealing with this wider agenda, in which the interests of every region are at stake and the participation of every region in the solutions is required. Pugwash efforts in the 1960s on the safeguards regime for the Non-Proliferation Treaty and on the Biological Weapons Convention, in the 1970s on a code of conduct for technology transfer for development, and from the 1970s to the present on the resolution of regional conflicts, on the Chemical Weapons Convention, and on limiting the accumulation and transfer of conventional weapons, have all benefited particularly from the organization’s multinational reach. The establishment, in the 1980s and 1990s, of Student/Young Pugwash chapters in many countries and the important work of Pugwash, throughout its history, on the desirability and feasibility of ultimately achieving a nuclear-weaponfree world, were also facilitated by our multilateral character.

At the same time, the strength of U.S. and Soviet participation in Pugwash in its first three decades, and the strength of U.S. and Russian participation today, has enabled our organization to treat, with some effectiveness, those aspects of the nuclear danger that have been dominated by the nuclear arsenals and postures of these powers. This dimension of Pugwash’s activities has included the organization’s efforts in the 1950s and 1960s on the technical basis for the Limited Test Ban Treaty, in the 1960s on the issues underlying the ABM Treaty, in the 1980s on the intermediate-range nuclear forces issue, and in the 1990s on managing – and shrinking – U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals and nuclear-weapon-production complexes in the aftermath of the Cold War.

My purpose in this capsule characterization of how the bilateral and multilateral facets of the Pugwash organization have related to our work over the past 38 years has not been to offer a history of Pugwash (which would be a larger task than befits this lecture) but only to suggest that the structure and historical preoccupations of our organization are reasonably well matched to the six-fold list of post-Cold-War security problems that I outlined earlier. All of these issues have evolved, of course, but at least the predecessors of all of them have been on the Pugwash agenda for many years. Accordingly, we think we have some ideas about what needs to be done. Let me take the remainder of this lecture to outline some of this thinking. In doing so, I will deal with the six problem areas in the order in which I presented them before.

First, with respect to the danger of use of the nuclear weapons still deployed, it is most important that all nations deploying nuclear weapons should move promptly to a “zero alert” nuclear posture. This would entail making it physically impossible to launch nuclear weapons except after a time delay of hours or even days (accomplished, for example, by demounting the warheads from delivery vehicles and storing them separately). As long as they were invulnerably based, nuclear weapons in this condition would retain their deterrent capacity against the use of nuclear weapons by others. (This so-called “minimum deterrent” role is the only rationale for nuclear weapons for which a halfway persuasive case can be made, and even that case, the Pugwash Council thinks, is provisional and temporary; but more about that in a moment.) In any event, such a deterrent function does not require that the reaction to a nuclear attack should be instantaneous, and giving up the possibility of an instantaneous reaction has the great benefit of practically eliminating the danger of accidental nuclear war. Accompanying the physical implementation of “zero alert” postures should be unilateral commitments of no-first-use and no threat of use of nuclear weapons by all nuclear-weapon states, pending early conclusion of a treaty to this effect.

Second, with respect to the danger of stagnation and reversal of ongoing arms-reduction processes, the immediate exercise of forceful leadership by President Clinton and President Yeltsin is called for in order to bring about the ratification, by the U.S. Senate and the Russian Duma, of both the START 2 agreement and the Chemical Weapons Convention. Russian agreement to ratify START 2 would be facilitated, for reasons both economic and military, by the early initiation of negotiations toward a START 3 agreement entailing deeper cuts, of tactical as well as strategic systems, and reserve warheads as well as deployed ones. Every effort should be made, as well, to engage the United Kingdom, France, China, and the undeclared nuclear-weapon states in the START 3 process. It also must be recognized that abandoning the ABM Treaty would surely doom START 2 as well as all efforts to achieve deeper reductions in U.S. and Russian offensive nuclear forces or to bring the possessors of smaller nuclear arsenals into the reduction process – all this for the illusion of a defense against nuclear attack, not the reality of one, which for fundamental reasons will remain out of reach.

Third, in the matter of proliferation of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, and of the delivery systems for these, the most important next steps are up to the existing nuclear-weapon powers. Prompt achievement of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty2 – without loopholes for low-yield tests or so-called “peaceful nuclear explosions” – is rightly seen by non-nuclear-weapon states as part of the basic bargain sealed by the recent indefinite extension of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Among non-nuclear-weapon states, pacts for mutual reassurance and joint monitoring of non-proliferation commitments – such as that agreed by Brazil and Argentina in 1994 – should be pursued as useful complements to the NPT and regional Nuclear Weapon Free Zones. Ultimately though, the prevention of proliferation will depend on the readiness of the nuclear-weapon states to continually reduce the prominence of nuclear weapons in their foreign and military policies and, indeed, to find ways of moving toward a nuclear-weapon-free world. The idea that a few nations are entitled to retain nuclear weapons for “deterrent” purposes indefinitely, while all others are expected to refrain from acquiring this ostensible benefit, is untenable in the long run. In the meantime, every statement or action by a nuclear-weapon state reinforcing the idea that nuclear weapons might have military utility will provoke interest on the part of other countries in acquiring them; and states that are thus provoked but lack the means to acquire them are likely to try to acquire instead the “poor man’s” weapons of mass destruction – chemical and biological weapons.

Fourth, with respect to the dismantling of surplus nuclear and chemical weapons and, especially, the protection and ultimate disposition of their active ingredients, the foot-dragging that has characterized much U.S. and Russian implementation of such measures – including, particularly, cooperative programs between the two countries that have been authorized and negotiated but only fractionally carried out – is deplorable. While this problem has received some high-level political attention on both sides, it needs more. The responsible bureaucrats in both countries, most of whom appear to be in no great hurry to get on with the job, need to be reminded in particular that protecting plutonium and highly enriched uranium – and ultimately disposing of these materials in ways that effectively preclude their reuse in weapons – represent not only one of the most urgent arms control and non-proliferation tasks but also one of the most cost-effective.

Fifth, with respect to the local conflicts raging day-in and day-out at all too many locations around the world, a strategy for abatement begins with the recognition that nearly all of the killing and maiming in these wars is being done by artillery, mortars, small arms, and land mines, and that most of this equipment in most cases is imported. It ought to be possible, therefore, to limit this violence by restricting international flows of light weapons; doing so poses practical difficulties, but a determined effort including strengthened export controls, scrapping stockpiles of surplus light weapons, and helping governments improve their border and customs controls is well worth undertaking. Adding a prohibition of anti-personnel land mines to the United Nations Inhumane Weapons Convention would also be worthwhile.3 Taking seriously the problem of local conflicts also compels attention to the evident inadequacies of the peacekeeping capabilities of the United Nations and of the other international security organizations, such as NATO, that exist in many regions. Clearly, these organizations can be no stronger than their member states are willing to allow them to be, and so far they have not been allowed to be strong enough. The post-Cold-War world needs a more powerful United Nations, probably with a standing volunteer force – owing loyalty directly to the UN rather than to contingents from individual nations – as recommended by the Commission on Global Governance.

The most intractable of the six security problems I have mentioned is likely to be the one that relates not to the “tools” of conflict – to weapons and military forces – but to the roots of conflicts in the inadequacies of the economic and environmental circumstances of a majority of the world’s people. The overwhelming economic and environmental predicaments of the poor cannot be solved by the poor alone without substantial cooperation from the rich, and, conversely, the predicament of the poor cannot be allowed to persist without peril to the rich. We live under one atmosphere, on the shores of one ocean, our countries linked by flows of people, money, goods, weapons, drugs, diseases, and ideas. Either we will achieve an environmentally sustainable prosperity for all, in a world where weapons of mass destruction have disappeared or become irrelevant, or we will all suffer from the chaos, conflict, and destruction resulting from the failure to achieve this.

Two of the most distinguished scientist-statesmen of our age – the American geochemist Harrison Brown and the Russian physicist Andrei Sakharov (Pugwash participants both) – concluded independently in works published in 1954 and 1968, respectively,4 that the cooperative effort needed to create the basis for durable prosperity, and hence durable security, for all the world’s people would require an investment equivalent to 10 to 20 percent of the rich countries’ GNPs, sustained over several decades. In 1995, these figures do not seem far wrong, but they are said to be politically unrealistic: nothing approaching them has ever been seriously contemplated by the world’s governments. Until this changes, a world free of war – correctly understood by the founders of the Pugwash conferences to be the essential concomitant of a world free of nuclear weapons – will remain just a dream.

Clearly, then, the work of Pugwash – and of all the other nongovernmental organizations that labored through the Cold War years to build up peaceful cooperation and build down military confrontation – is far from done. The agenda of dangers still to be overcome is hardly less daunting than the one faced by the founders of the Pugwash Conferences in the Cold War gloom of the 1950s. But the world did finally escape the Cold War, and with a bit of luck, a bit of wisdom, and a lot of work it may yet escape the remaining dangers, too. It is a pleasure to thank, on behalf of the Pugwash organization, the thousands of participants in Pugwash meetings whose efforts, I think, have contributed measurably to making a safer and better world; to thank the many sponsors whose support over the years made the activities of Pugwash possible; and to thank, once again, the Norwegian Nobel Committee for this most welcome recognition of our past work and most helpful impetus for the work ahead.

1. The U.S. ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997, the 75th nation to do so.

2. In 1996 the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was signed by the U.S., the USSR and many other nations.

3. The United Nations Inhuman Weapons Convention, which prohibited the production and use of weapons “which may be deemed to be excessively injurious or to have indeterminate effects” was approved in 1981 and ratified by 25 countries by 1987. It did not explicitly ban landmines, and it was the failure of the review conference in 1997 to do this which led to the successful efforts of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines to bring about the into effect in March 1999. For this achievement the Nobel Peace Prize for 1997 was awarded jointly to the ICBL and its coordinator, Jody Williams of the United States.

4. See The Challenge of Man’s Future, by Harrison Scott Brown (New York: Viking, 1954) and Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom by Andrei Sakharov (New York: W.W. Norton, 1968).

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.