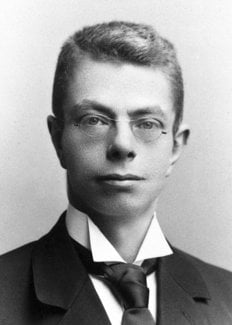

Pieter Zeeman

Biographical

Pieter Zeeman was born on May 25, 1865, at Zonnemaire, a small village in the isle of Schouwen, Zeeland, The Netherlands, as the son of the local clergyman Catharinus Forandinus Zeeman and his wife, née Wilhelmina Worst. After having finished his secondary school education at Zierikzee, the main town of the island, he went to Delft for two years to receive tuition in the classical languages, an adequate knowledge of which was required at that time for entrance to the university. Taking up his abode at the house of Dr. J.W. Lely, conrector of the Gymnasium and brother of Dr. C. Lely (Minister of Public Works and known for initiating and developing the work for reclamation of the Zuyderzee), Zeeman came into an environment which was beneficial for the development of his scientific talents. It was here also that he came into contact with Kamerlingh Onnes (Nobel Prize in Physics for 1913), who was twelve years his senior. Zeeman’s wide reading, which included a proper mastery of works such as Maxwell’s Heat, and his passion for performing experiments amazed Kamerlingh Onnes in no small degree, and formed the basis for a fruitful friendship between the two scientists.

Zeeman entered Leyden University in 1885 and became mainly a pupil of Kamerlingh Onnes (mechanics) and Lorentz (experimental physics): the latter was later to share the Nobel Prize with him. An early reward came in 1890 when he was appointed assistant to Lorentz, enabling him to participate in an extensive research programme which included the study of the Kerr effect – an important foundation for his future great work. He obtained his doctor’s degree in 1893, after which he left for F. Kohlrausch’s institute at Strasbourg, where for one semester he carried out work under E. Cohn. He returned to Leyden in 1894 and became “privaat-docent” (extra-mural lecturer) from 1895 to 1897.

In 1897, the year following his great discovery of the magnetic splitting of spectral lines, he was called to a lectureship at the University of Amsterdam; in 1900 came his appointment as Extraordinary Professor. In 1908 Van der Waals (Nobel Prize in Physics for 1910) reached the retiring age of 70 and Zeeman was chosen as his successor, at the same time functioning as Director of the Physics Laboratory. In 1923 a new laboratory, specially erected for him, was put at his disposal, a prominent feature being a concrete block weighing a quarter of a million kilograms, erected free from the floor, as a suitable platform for vibration-free experiments. The institute is now known as the Zeeman Laboratory of Amsterdam University. Many world-famous scientists have visited Zeeman there or worked with him for some time. He remained in this dual function for 35 years – on numerous occasions refusing an invitation to occupy a Chair abroad – until in 1935 he had to resign on account of his pensionable age. An accomplished teacher and of kind disposition he was much loved by his pupils. One of these was C.J. Bakker, who was from 1955 until his untimely death in an aircraft accident in 1960 the General Director of the Organisation Européenne pour la Recherche Nucléaire (CERN) at Geneva. Another worker in his laboratory was S. Goudsmit, who in 1925 with G.E. Uhlenbeck originated the concept of electron spin.

Zeeman’s talent for natural science first became apparent in 1883, when, while still attending the secondary school, he gave an apt description and drawing of an aurora borealis – then clearly to be observed in his country – which was published in Nature. (The Editor praised the meticulous observations of «Professor Zeeman in his observatory at Zonnemaire»!)

Zeeman’s main theme of investigation has always concerned optical phenomena. His first treatise Mesures relatives du phénomène de Kerr, written in 1892, was rewarded with a Gold Medal from the Dutch Society of Sciences at Haarlem; his doctor’s thesis dealt with the same subject. In Strasbourg he studied the propagation and absorption of electrical waves in fluids. His principal work, however, was the study of the influence of magnetism on the nature of light radiation, started by him in the summer of 1896, which formed a logical continuation of his investigation into the Kerr effect. The discovery of the so-called Zeeman effect, for which he has been awarded the Nobel Prize, was communicated to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Amsterdam – through H. Kamerlingh Onnes (1896) and J.D. van der Waals (1897) – in the form of papers entitled Over den Invloed eener Magnetisatie op den Aard van het door een Stof uitgezonden Licht (On the influence of a magnetization on the nature of light emitted by a substance) and Over Doubletten en Tripletten in het Spectrum teweeggebracht door Uitwendige Magnetische Krachten (On doublets and triplets in the spectrum caused by external magnetic forces) I, II and III. (The English translations of these papers appeared in The Philosophical Magazine; of the first paper a French version appeared in Archives Néerlandaises des Sciences Exactes et Naturelles, and in a short form in German in Verhandlungen der Physikalischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin.)

The importance of the discovery can at once be judged by the fact that at one stroke the phenomenon not only confirmed Lorentz’ theoretical conclusions with regard to the state of polarization of the light emitted by flames, but also demonstrated the negative nature of the oscillating particles, as well as the unexpectedly high ratio of their charge and mass (e/m). Thus, when in the following year the discovery of the existence of free electrons in the form of cathode rays was established by J.J. Thomson, the identity of electrons and the oscillating light particles could be established from the negative nature and the e/m ratio of the particles. The growing number of observations made by other investigators on studying the effects of using various substances as light emitters – not all of them explicable by Lorentz’ original theory (the so-called «anomalous Zeeman effect» could only adequately be explained at a later date, with the advent of Bohr’s atomic theory, quantum wave mechanics, and the concept of the electron spin) – was assembled by him in his book Researches in Magneto-Optics (London 1913, German translation in 1914). Not only has the Zeeman effect thrown much light on the mechanism of light radiation and on the nature of matter and electricity, but its immense importance lies in the fact that even to this day it offers the ultimate means for revealing the intimate structure of the atom and the nature and behaviour of its components. It still serves as the final test in any new theory of the atom.

Already in his second communication Zeeman expressed the opinion that the accepted existence of strong magnetic fields on the surface of the sun could be verified, since these should alter spectral lines derived from the celestial body. (It is typical of Zeeman to extend physical concepts into the realm of celestial phenomena.) In a letter to him (1908) the astronomer G.E. Hale, Director of Mount Wilson Observatory, corroborated this opinion by means of photographs which indicated that in solar vortices the spectral lines indeed appeared to be affected by magnetic fields. Even the theoretical prediction concerning the probable interrelationship between the directions of polarization and those of the magnetic fields was subsequently confirmed by Hale.

With regard to Zeeman’s activities outside the field of the magnetic splitting of spectral lines, mention should first be made of his work on the Doppler effect in optics and in canal rays (laboratory tests). A second field of study was that on the propagation of light in moving media (justification of the existence of the Lorentz-term in the Fresnel drag coefficient). Other investigations were those into the influence of the magnetic moment of the nucleus on the hyperfine structure of spectral lines. He also succeeded, with J. de Gier, in discovering a number of new isotopes (38Ar, 64Ni, amongst others) by means of Thomson’s parabola mass spectrograph. Zeeman’s predilection for testing fundamental laws also found expression in his verification – carried out with an accuracy of 7 – of the equality of heavy and inert masses.

Zeeman was Honorary Doctor of the Universities of Göttingen, Oxford, Philadelphia, Strasbourg, Liège, Ghent, Glasgow, Brussels and Paris. He was also a member or honorary member of numerous learned academies, including the very rare distinction of Associé Etranger of the Académie des Sciences of Paris. He was also member and Chairman of the Commission Internationale des Poids et Mesures, Paris. Appointed member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Amsterdam in 1898, he served as the Secretary of the Mathematical-Physical Section from 1912 to 1920. Among the other distinctions may be mentioned the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society of London, the Prix Wilde of the Academie des Sciences of Paris, the Baumgartner-Preis of the Akademie der Wissenschaften of Vienna, the Matteucci Medal of the Italian Society of Sciences, the Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia, the Henry Draper Medal of the National Academy of Sciences of Washington. He was also made a Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau and Commander of the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

Outside his field of study Zeeman showed much interest in literature and the stage. An entertaining host, he loved to invite his collaborators and pupils to dine with him at his home, an event preceded by a learned talk in his study and followed by a gathering in the family circle.

Zeeman married Johanna Elisabeth Lebret in 1895; they had one son and three daughters. During the last year of his professorship he suffered from ill-health. He died after a short illness on October 9, 1943.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.