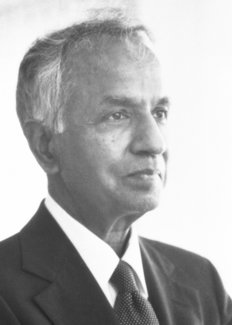

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Biographical

I was born in Lahore (then a part of British India) on the 19th of October 1910, as the first son and the third child of a family of four sons and six daughters. My father, Chandrasekhara Subrahmanya Ayyar, an officer in Government Service in the Indian Audits and Accounts Department, was then in Lahore as the Deputy Auditor General of the Northwestern Railways. My mother, Sita (neé Balakrishnan) was a woman of high intellectual attainments (she translated into Tamil, for example, Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House), was passionately devoted to her children, and was intensely ambitious for them.

My early education, till I was twelve, was at home by my parents and by private tuition. In 1918, my father was transferred to Madras where the family was permanently established at that time.

In Madras, I attended the Hindu High School, Triplicane, during the years 1922-25. My university education (1925-30) was at the Presidency College. I took my bachelor’s degree, B.Sc. (Hon.), in physics in June 1930. In July of that year, I was awarded a Government of India scholarship for graduate studies in Cambridge, England. In Cambridge, I became a research student under the supervision of Professor R.H. Fowler (who was also responsible for my admission to Trinity College). On the advice of Professor P.A.M. Dirac, I spent the third of my three undergraduate years at the Institut för Teoretisk Fysik in Copenhagen.

I took my Ph.D. degree at Cambridge in the summer of 1933. In the following October, I was elected to a Prize Fellowship at Trinity College for the period 1933-37. During my Fellowship years at Trinity, I formed lasting friendships with several, including Sir Arthur Eddington and Professor E.A. Milne.

While on a short visit to Harvard University (in Cambridge, Massachusetts), at the invitation of the then Director, Dr. Harlow Shapley, during the winter months (January-March) of 1936, I was offered a position as a Research Associate at the University of Chicago by Dr. Otto Struve and President Robert Maynard Hutchins. I joined the faculty of the University of Chicago in January 1937. And I have remained at this University ever since.

During my last two years (1928-30) at the Presidency College in Madras, I formed a friendship with Lalitha Doraiswamy, one year my junior. This friendship matured; and we were married (in India) in September 1936 prior to my joining the University of Chicago. In the sharing of our lives during the past forty-seven years, Lalitha’s patient understanding, support, and encouragement have been the central facts of my life.

After the early preparatory years, my scientific work has followed a certain pattern motivated, principally, by a quest after perspectives. In practise, this quest has consisted in my choosing (after some trials and tribulations) a certain area which appears amenable to cultivation and compatible with my taste, abilities, and temperament. And when after some years of study, I feel that I have accumulated a sufficient body of knowledge and achieved a view of my own, I have the urge to present my point of view, ab initio, in a coherent account with order, form, and structure.

There have been seven such periods in my life: stellar structure, including the theory of white dwarfs (1929-1939); stellar dynamics, including the theory of Brownian motion (1938-1943); the theory of radiative transfer, including the theory of stellar atmospheres and the quantum theory of the negative ion of hydrogen and the theory of planetary atmospheres, including the theory of the illumination and the polarization of the sunlit sky (1943-1950); hydrodynamic and hydromagnetic stability, including the theory of the Rayleigh-Bénard convection (1952-1961); the equilibrium and the stability of ellipsoidal figures of equilibrium, partly in collaboration with Norman R. Lebovitz (1961-1968); the general theory of relativity and relativistic astrophysics (1962-1971); and the mathematical theory of black holes (1974- 1983). The monographs which resulted from these several periods are:

1. An Introduction to the Study of Stellar Structure (1939, University of Chicago Press; reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., 1967).

2a. Principles of Stellar Dynamics (1943, University of Chicago Press; reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., 1960).

2b. ‘Stochastic Problems in Physics and Astronomy’, Reviews of Modern Physics, 15, 1 – 89 (1943); reprinted in Selected Papers on Noise and Stochastic Processes by Nelson Wax, Dover Publications, Inc., 1954.

3. Radiative Transfer (1950, Clarendon Press, Oxford; reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., 1960).

4. Hydrodynamic and Hydromagnetic Stability (1961, Clarendon Press, Oxford; reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., 1981).

5. Ellipsoidal Figures of Equilibrium (1968; Yale University Press).

6. The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (1983, Clarendon Press, Oxford).

However, the work which appears to be singled out in the citation for the award of the Nobel Prize is included in the following papers:

‘The highly collapsed configurations of a stellar mass’, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 91, 456-66 (1931).

‘The maximum mass of ideal white dwarfs’, Astrophys. J., 74, 81 – 2 (1931).

‘The density of white dwarfstars’, Phil. Mag., 11, 592 – 96 (1931).

‘Some remarks on the state of matter in the interior of stars’, Z. f. Astrophysik, 5, 321-27 (1932).

‘The physical state of matter in the interior of stars’, Observatory, 57, 93 – 9 (1934)

‘Stellar configurations with degenerate cores’, Observatory, 57, 373 – 77 (1934).

‘The highly collapsed configurations of a stellar mass’ (second paper), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 95, 207 – 25 (1935).

‘Stellar configurations with degenerate cores’, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 95, 226-60 (1935).

‘Stellar configurations with degenerate cores’ (second paper), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 95, 676 – 93 (1935).

‘The pressure in the interior of a star’, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 96, 644 – 47 (1936).

‘On the maximum possible central radiation pressure in a star of a given mass’, Observatory, 59, 47 – 8 (1936).

‘Dynamical instability of gaseous masses approaching the Schwarzschild limit in general relativity’, Phys. Rev. Lett., 12, 114 – 16 (1964); Erratum, Phys. Rev. Lett., 12, 437 – 38 (1964).

‘The dynamical instability of the white-dwarf configurations approaching the limiting mass’ (with Robert F. Tooper), Astrophys. J., 139, 1396 – 98 (1964).

‘The dynamical instability of gaseous masses approaching the Schwarzschild limit in general relativity’, Astrophys. J., 140, 417 – 33 (1964).

‘Solutions of two problems in the theory of gravitational radiation’, Phys. Rev. Lett., 24, 611 – 15 (1970); Erratum, Phys. Rev. Lett., 24, 762 (1970).

‘The effect of graviational radiation on the secular stability of the Maclaurin spheroid’, Astrophys. J., 161, 561 – 69

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Subramanyan Chandrasekhar died on August 21, 1995.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.