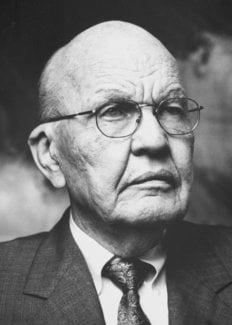

Jack Kilby

Biographical

The Nobel Committee has asked me to discuss my life story, so I guess I should begin at the beginning.

I was born in 1923 in Great Bend, Kansas, which got its name because the town was built at the spot where the Arkansas River bends in the middle of the state. I grew up among the industrious descendents of the western settlers of the American Great Plains.

My father ran a small electric company that had customers scattered across the rural western part of Kansas. While I was in high school, a huge ice storm knocked down most of the poles that carried the telephone and electric power lines. My father worked with amateur radio operators to communicate with areas where customers had lost their power and phone service.

My dad’s goal was to do whatever it took to run his business and to help people, but I thought that amateur radio was a fascinating subject. It sparked my interest in electronics, and that’s when I decided that this field was something I wanted to pursue.

I also was a fan of broadcast radio. In the 1940s, I especially enjoyed listening to Big Band music. Even today, there’s a radio station in Dallas that plays this kind of music, and with a little luck, I don’t have to listen to much else.

After high school, I studied electrical engineering at the University of Illinois. Most of my classes were in electrical power, but because of my childhood interest in electronics, I also took some vacuum tube engineering physics classes.

I graduated in 1947, just one year before Bell Labs announced the invention of the transistor. It meant that my vacuum?tube classes were about to be come obsolete, but it offered great opportunities to put my physics studies to good use.

In line with the interests that occupied my thoughts in Great Bend, I hired on with an electronics manufacturer in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that made parts for radios, televisions and hearing aids.

While in Milwaukee, I took evening classes at the University of Wisconsin towards a master’s degree in electrical engineering. Working and going to school at the same time presents some challenges, but it can be done and its well worth the effort.

In 1958, my wife and I moved to Dallas, Texas, when I took job with Texas Instruments. TI was the only company that agreed to let me work on electronic component miniaturization more or less full time, and it turned out to be a great fit.

After proving that integrated circuits were possible, I headed teams that built the first military systems and the first computer incorporating integrated circuits. I also worked on teams that invented the handheld calculator and the thermal printer, which was used in portable data terminals.

In 1970 I took a leave of absence from TI to do some independent work. While on leave, one of the things I worked on was how to apply silicon technology to help generate electrical power from sunlight.

From 1978 to 1984, I spent much of my time as a Distinguished Professor of Electrical Engineering at Texas A&M University. The “distinguished” part is in the eye of the beholder, and I really didn’t do much “professing.” However, I did have a rewarding time doing research and working with students and faculty on various projects.

I officially retired from TI in the 1980s, but I have maintained a significant involvement with the company that continues to this day.

Along the way, I’ve been honored to receive awards such as the National Medal of Science and to be inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Seeing your name alongside the likes of Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and the Wright Brothers is a very humbling experience, and I appreciate these and the other honors very much.

Receiving the Nobel Prize in Physics was a completely unexpected, yet very pleasant surprise. I had to start my pot of coffee very early the morning I received the news that I had been chosen.

It’s gratifying to see the committee recognize applied physics, since the award is typically given for basic research. I do think there’s a symbiosis as the application of basic research often provides tools that then enhance the process of basic research. Certainly, the integrated circuit is a good example of that. Whether the research is applied or basic, we all “stand upon the shoulders of giants,” as Isaac Newton said. I’m grateful to the innovative thinkers who came before me, and I admire the innovators who have followed.

Four decades of hindsight is perhaps a unique experience among those who have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. As I noted in my lecture, there were various efforts to solve the electronic miniaturization problem at the time I invented the integrated circuit. Humankind eventually would have solved the matter, but I had the fortunate experience of being the first person with the right idea and the right resources available at the right time in history.

I would like to mention another right person at the right time, namely Robert Noyce, a contemporary of mine who worked at Fairchild Semiconductor. While Robert and I followed our own paths, we worked hard together to achieve commercial acceptance for integrated circuits. If he were still living, I have no doubt we would have shared this prize.

Now that I am retired, I still occasionally consult on various industry and government projects, mostly in the area of semiconductors. I also serve on the board of directors of a company or two.

People often ask me what I’m proud of, and, of course, the integrated circuit is at the top of the list. I’m also proud of my wonderful family. I have two daughters and five granddaughters, so you could say that the Kilbys specialized in girls.

I’ve reached the age where young people frequently ask for my advice. All I can really say is that electronics is a fascinating field that I continue to find fulfilling. The field is still growing rapidly, and the opportunities that are ahead are at least as great as they were when I graduated from college. My advice is to get involved and get started.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Jack S. Kilby died on June 20, 2005.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.