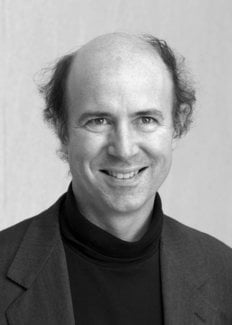

Frank Wilczek

Biographical

The most deeply formative events of my scientific career long preceded my first contact with the research community; indeed, some of them preceded my birth.

My grandparents emigrated from Europe in the aftermath of World War I, as young teenagers; on my father’s side they came from Poland and on my mother’s side from Italy, near Naples. My grandparents arrived with nothing, and no knowledge of English. My grandfathers were a blacksmith and a mason, respectively. Both my parents were born on Long Island, in 1926, and they have lived there ever since. I was born in 1951, and grew up in a place called Glen Oaks, which is in the northeast corner of Queens, barely within the city limits of New York City.

I’ve always loved all kinds of puzzles, games, and mysteries. Some of my earliest memories are about the questions I “worked on” even before I went to school. When I was learning about money, I spent a lot of time trying out various schemes of exchanging different kinds of money (e.g., pennies, nickels, and dimes) in complicated ways back and forth, hoping to discover a way to come out ahead. Another project was to find ways of getting very big numbers in a few steps. I discovered simple forms of repeated exponentiation and recursion for myself. Generating large numbers made me feel powerful.

With these inclinations, I suspect I was destined for some kind of intellectual work. A few special circumstances led me to science, and eventually to theoretical physics.

My parents were children during the time of the Great Depression, and their families struggled to get by. This experience shaped many of their attitudes, and especially their aspirations for me. They put very great stock in education, and in the security that technical skill could bring. When I did well in school they were very pleased, and I was encouraged to think about becoming a doctor or an engineer. As I was growing up my father, who worked in electronics, was taking night classes. Our little apartment was full of old radios and early-model televisions, and with the books he was studying. It was the time of the Cold War. Space exploration was a new and exciting prospect, nuclear war a frightening one; both were ever-present in newspapers, TV, and movies. At school, we had regular air raid drills. All this made a big impression on me. I got the idea that there was secret knowledge that, when mastered, would allow Mind to control Matter in seemingly magical ways.

Another thing that shaped my thinking was religious training. I was brought up as a Roman Catholic. I loved the idea that there was a great drama and a grand plan behind existence. Later, under the influence of Bertrand Russell’s writings and my increasing awareness of scientific knowledge, I lost faith in conventional religion. A big part of my later quest has been trying to regain some of the sense of purpose and meaning that was lost. I’m still trying.

I went to public schools in Queens, and was fortunate to have excellent teachers. Because the schools were big, they could support specialized and advanced classes. At Martin van Buren High School there was a group of thirty or so of us who went to many such classes together, and both supported and competed with one another. More than half of us went on to successful scientific or medical careers.

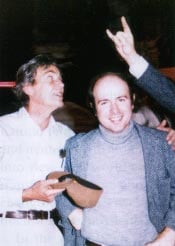

I arrived at the University of Chicago with large but amorphous ambitions. I flirted with brain science, but soon decided that the central questions were not ready for mathematical treatment, and that I lacked the patience for laboratory work. I read voraciously in many subjects, but I wound up majoring in mathematics, largely because doing that gave me the most freedom. During my last term at Chicago, I took a course about the use of symmetry and group theory in physics from Peter Freund. He was an extremely enthusiastic and inspiring teacher, and I felt an instinctive resonance with the material. I went to Princeton University as a graduate student in the math department, but kept a close eye on what was going on in physics. I became aware that deep ideas involving mathematical symmetry were turning up at the frontiers of physics; specifically, the gauge theory of electroweak interactions, and the scaling symmetry in Wilson’s theory of phase transitions. I started to talk with a young professor named David Gross, and my proper career as a physicist began.

The great event of my early career was to help discover the basic theory of the strong force, QCD. That is the subject of the following lecture. The equations of QCD are based on gauge symmetry principles, and we make progress with them using (approximate) scaling symmetry. It was very gratifying to find that the ideas I admired as a student could be used to get a powerful and accurate theory for an important part of fundamental physics. I continue to apply these ideas in new ways, and I am certain that they have a great future.

An aspect of my later work that is not much reflected in the lecture, has been to use insights and methods from “fundamental” physics to address “applied” questions, and vice versa. I’m not sure that fractional quantum numbers, transmuted quantum statistics, exotic superfluidities, or the gauge theory of swimming at low Reynolds number have really arrived as applied physics (yet?), but I’ve derived a lot of joy from my discoveries in these areas.

To me, the unity of knowledge is a living ideal and goal. I continue, as in my student days, to read voraciously in many subjects, and to think about them. I hope to further expand the horizons of my writing and work in the future.

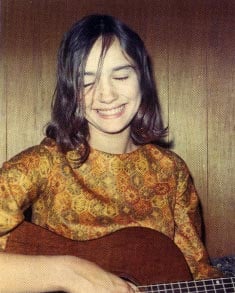

I’ve been blessed with a wife, Betsy Devine, and two daughters, Amity and Mira, who’ve been an inexhaustible source of joy and entertainment.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.