Popular information

Popular science background:

Blue LEDs – Filling the world with new light (pdf)

Populärvetenskaplig information:

Blå lysdioder – en uppfinning som sprider nytt ljus över världen (pdf)

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2014

Blue LEDs – Filling the world with new light

Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura are rewarded for inventing a new energy-efficient and environment-friendly light source – the blue light-emitting diode (LED). In the spirit of Alfred Nobel, the Prize awards an invention of greatest benefit to mankind; by using blue LEDs, white light can be created in a new way. With the advent of LED lamps we now have more long-lasting and more efficient alternatives to older light sources.

When Akasaki, Amano and Nakamura arrive in Stockholm in early December to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony, they will hardly fail to notice the light from their invention glowing in virtually all the windows of the city. The white LED lamps are energy-efficient, long-lasting and emit a bright white light. Moreover, and unlike fluorescent lamps, they do not contain mercury.

Red and green light-emitting diodes have been with us for almost half a century, but blue light was needed to really revolutionize lighting technology. Only the triad of red, green and blue can produce the white light that illuminates the world for us. Despite the high stakes and great efforts undertaken in the research community as well as in industry, blue light remained a challenge for three decades.

Akasaki worked with Amano at Nagoya University while Nakamura was employed at Nichia Chemicals, a small company located in Tokushima on the island of Shikoku. When they obtained bright blue light beams from their semiconductors, the gates opened up for a fundamental transformation of illumination technology. Incandescent light bulbs had lit the 20th century; the 21st century will be lit by LED lamps.

Saving energy and resources

A light-emitting diode consists of a number of layered semiconductor materials. In the LED, electricity is directly converted into light particles, photons, leading to efficiency gains compared to other light sources where most of the electricity is converted to heat and only a small amount into light. In incandescent bulbs, as well as in halogen lamps, electric current is used to heat a wire filament, making it glow. In fluorescent lamps (previously referred to as low-energy lamps, but with the advent of LED lamps that label has lost its meaning) a gas discharge is produced creating both heat and light.

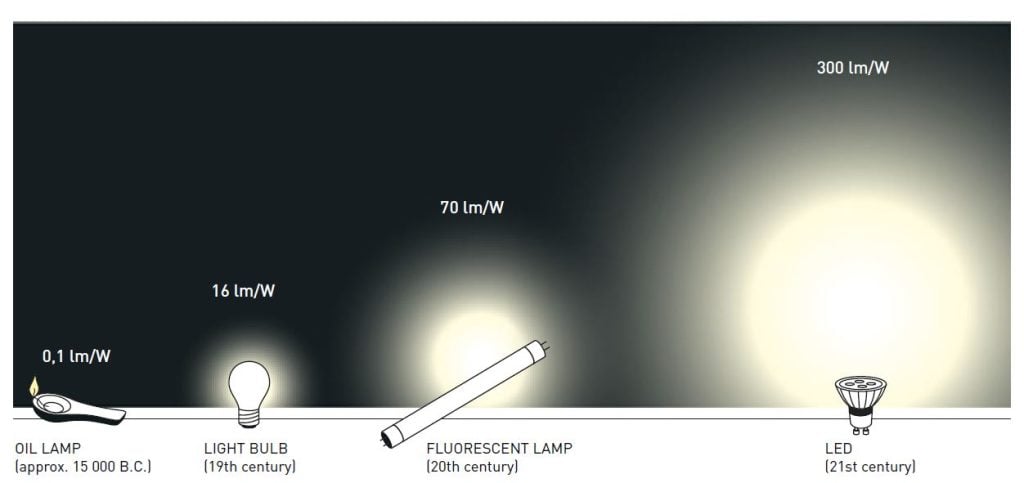

Thus, the new LEDs require less energy in order to emit light compared to older light sources. Moreover, they are constantly improved, getting more efficient with higher luminous flux (measured in lumen) per unit electrical input power (measured in watt). The most recent record is just over 300 lumen/watt, which can be compared to 16 for regular light bulbs and close to 70 for fluorescent lamps. As about one fourth of world electricity consumption is used for lighting purposes, the highly energy-efficient LEDs contribute to saving the Earth’s resources.

LEDs are also more long-lasting than other lamps. Incandescent bulbs tend to last 1,000 hours, as heat destroys the filament, while fluorescent lamps usually last around 10,000 hours. LEDs can last for 100,000 hours, thus greatly reducing materials consumption.

Creating light in a semiconductor

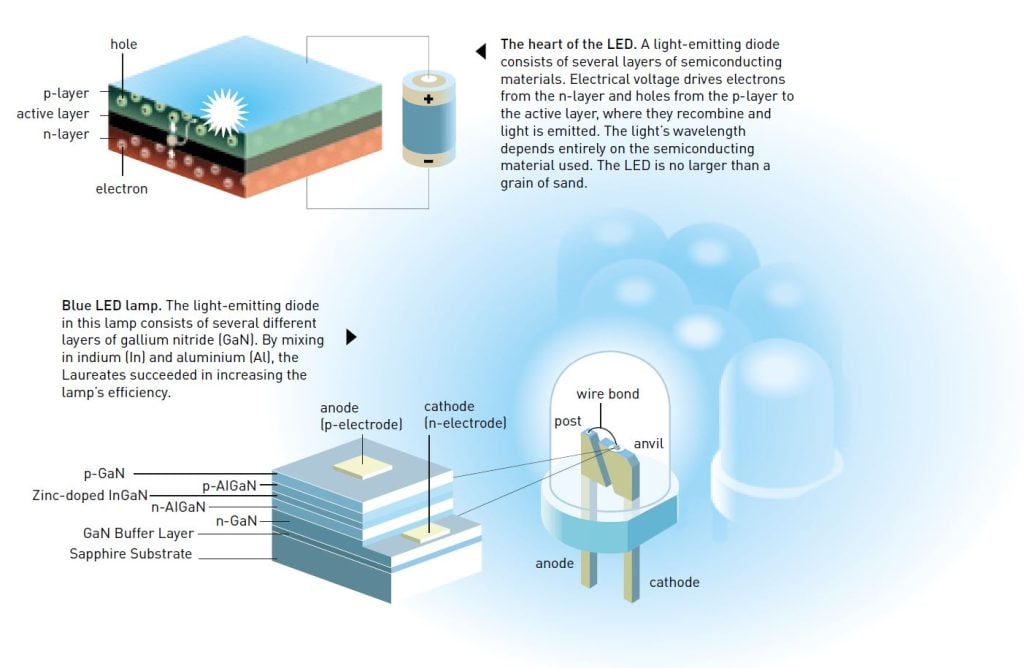

LED technology originates in the same art of engineering that gave us mobile phones, computers and all modern electronics equipment based on quantum phenomena. A light-emitting diode consists of several layers: an n-type layer with a surplus of negative electrons, and a p-type layer with an insufficient amount of electrons, also referred to as a layer with a surplus of positive holes.

Between them is an active layer, to which the negative electrons and the positive holes are driven when an electric voltage is applied to the semiconductor. When electrons and holes meet they recombine and light is created. The light’s wavelength depends entirely on the semiconductor; blue light appears at the short-wave end of the rainbow and can only be produced in some materials.

The first report of light being emitted from a semiconductor was authored in 1907 by Henry J. Round, a co-worker of Guglielmo Marconi, Nobel Prize Laureate 1909. Later on, in the 1920s and 1930s, in the Soviet Union, Oleg V. Losev undertook closer studies of light emission. However, Round and Losev lacked the knowledge to truly understand the phenomenon. It would take a few decades before the prerequisites for a theoretical description of this so-called electroluminescence were created.

The red light-emitting diode was invented in the end of the 1950s. They were used, for instance, in digital watches and calculators, or as indicators of on/off-status in various appliances. At an early stage it was evident that a light-emitting diode with short wavelength, consisting of highly energetic photons – a blue diode – was needed to create white light. Many laboratories tried, but without success.

Challenging convention

The Laureates challenged established truths; they worked hard and took considerable risks. They built their equipment themselves, learnt the technology, and carried out thousands of experiments. Most of the time they failed, but they did not despair; this was laboratory artistry at the highest level.

Gallium nitride was the material of choice for both Akasaki and Amano as well as for Nakamura, and they eventually succeeded in their efforts, even though others had failed before them. Early on, the material was considered appropriate for producing blue light, but practical difficulties had proved enormous. No one was able to grow gallium nitride crystals of high enough quality, since it was seen as a hopeless endeavour to try to produce a fitting surface to grow the gallium nitride crystal on. Moreover, it was virtually impossible to create p-type layers in this material.

Nonetheless, Akasaki was convinced by previous experience that the choice of material was correct, and continued working with Amano, who was a Ph.D.-student at Nagoya University. Nakamura at Nichia also chose gallium nitride before the alternative, zinc selenide, which others considered to be a more promising material.

Fiat lux – let there be light

In 1986, Akasaki and Amano were the first to succeed in creating a high-quality gallium nitride crystal by placing a layer of aluminium nitride on a sapphire substrate and then growing the high quality gallium nitride on top of it. A few years later, at the end of the 1980s, they made a breakthrough in creating a p-type layer. By coincidence Akasaki and Amano discovered that their material was glowing more intensely when it was studied in a scanning electron microscope. This suggested that the electronic beam from the microscope was making the p-type layer more efficient. In 1992 they were able to present their first diode emitting a bright blue light.

Nakamura began developing his blue LED in 1988. Two years later, he too, succeeded in creating high-quality gallium nitride. He found his own clever way of creating the crystal by first growing a thin layer of gallium nitride at low temperature, and growing subsequent layers at a higher temperature.

Nakamura could also explain why Akasaki and Amano had succeeded with their p-type layer: the electron beam removed the hydrogen that was preventing the p-type layer to form. For his part, Nakamura replaced the electron beam with a simpler and cheaper method: by heating the material he managed to create a functional p-type layer in 1992. Hence, Nakamura’s solutions were different from those of Akasaki and Amano.

During the 1990s, both research groups succeeded in further improving their blue LEDs, making them more efficient. They created different gallium nitride alloys using aluminium or indium, and the LED’s structure became increasingly complex.

Akasaki, together with Amano, as well as Nakamura, also invented a blue laser in which the blue LED, the size of a grain of sand, is a crucial component. Contrary to the dispersed light of the LED, a blue laser emits a cutting-sharp beam. Since blue light has a very short wavelength, it can be packed much tighter; with blue light the same area can store four times more information than with infrared light. This increase in storage capacity quickly led to the development of Blu-ray discs with longer playback times, as well as better laser printers.

Many home appliances are also equipped with LEDs. They shine their light on LCD-screens in television sets, computers and mobile phones, for which they also provide a lamp and a flash for the camera.

A bright revolution

The Laureates’ inventions revolutionized the field of illumination technology. New, more efficient, cheaper and smarter lamps are developed all the time. White LED lamps can be created in two different ways. One way is to use blue light to excite a phosphor so that it shines in red and green. When all colours come together, white light is produced. The other way is to construct the lamp out of three LEDs, red, green and blue, and let the eye do the work of combining the three colours into white.

LED lamps are thus flexible light sources, already with several applications in the field of illumination – millions of different colours can be produced; the colours and intensity can be varied as needed. Colourful light panels, several hundred square metres in size, blink, change colours and patterns. And everything can be controlled by computers. The possibility to control the colour of light also implies that LED lamps can reproduce the alternations of natural light and follow our biological clock. Greenhouse-cultivation using artificial light is already a reality.

The LED lamp also holds great promise when it comes to the possibility of increasing the quality of life for the more than 1.5 billion people who currently lack access to electricity grids, as the low power requirements imply that the lamp can be powered by cheap local solar power. Moreover, polluted water can be sterilised using ultraviolet LEDs, a subsequent elaboration of the blue LED.

Links and further reading

Articles

Zheludev, N. (2007) The life and times of the LED – a 100-year history, Nature photonics, vol. 1, April

Schubert, E. F. and Kim, J. K. (2005) Solid-State Light Sources Getting Smart, Science, 308, 1274

Savage, N. (2000) LEDs light the future, Technology Review, vol. 103, no 5, p. 38–44, September–October

Book

Khanna, V. K. (2014) Fundamentals of Solid State Lighting: LEDs, OLEDs, and Their Application in Illumination and Displays, CRC Press

The Laureates

ISAMU AKASAKI

Japanese citizen. Born 1929 in Chiran, Japan. Ph.D. 1964 from Nagoya University, Japan. Professor at Meijo University, Nagoya, and Distinguished Professor at Nagoya University, Japan.

http://en.nagoya-u.ac.jp/people/distinguished_award_recipients/nagoya_university_distinguished_professor_isamu_akasaki.html

HIROSHI AMANO

Japanese citizen. Born 1960 in Hamamatsu, Japan. Ph.D. 1989 from Nagoya University, Japan. Professor at Nagoya University, Japan.

http://profs.provost.nagoya-u.ac.jp/view/html/100001778_en.html

SHUJI NAKAMURA

American citizen. Born 1954 in Ikata, Japan. Ph.D. 1994 from University of Tokushima, Japan. Professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA.

www.sslec.ucsb.edu/nakamura/

Science Editors: Lars Bergström, Per Delsing, Anne L’Huillier and Olle Inganäs, the Nobel Committee for Physics

Text and photo: Joanna Rose

Illustrations: © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Editor: Sara Gustavsson

© The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.