by Åke Erlandsson*

“A recluse without books and ink is already in life a dead man”

– Alfred Nobel

During his lifetime, Alfred Nobel was undoubtedly more renowned for his work as an inventor and industrialist than for his interests in the arts. However, to understand his versatility, his complex and at times contradictory nature, these interests that were also vital to him have to be taken into account as well.

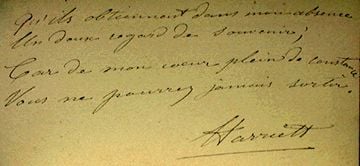

There are thirteen red gilt-edged small volumes by Byron in Nobel’s library. Inside the first volume is a handwritten poem in French from “Harriett”. Who was Harriett? Who was the receiver? Qu’ils obtiennent dans mon absence Un doux regard de souvenir; Car de mon coeur plein de constance Vous ne pourrez jamais sortir.

Although Nobel belonged to the realm of his work and inventions, his second home was in literature and writing. After his death he left a private library of over 1500 volumes, mostly fiction in the original language, works by the great writers of the 19th century, but also the classics and works by philosophers, theologians, historians and other scientists.

He also left a voluminous collection of letters, a handful of poems he himself had written in his youth and some early drafts of analytical novels, I ljusaste Afrika (In Brightest Africa, 1861) and Systrarna (The Sisters, 1862). Towards the end of his life, when his inventions and business activities left him more time, he drafted the outline of a satirical comedy, The Patent Bacillus (1895), and published a tragedy, Nemesis (1896). Nobel’s will, dated 1895, is the final testimony to his lifelong love of poetry: one of the prizes was to be awarded to “the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”.

St. Petersburg (1842-1863)

During his education in St. Petersburg, Alfred Nobel was taught by outstanding private tutors, mainly chemistry and physics, but also literature and philosophy. He proved to be a precocious pupil, exceptionally gifted, but quiet and introvert. He learnt a great deal on his own – French by translating Voltaire, first into Swedish and then back into French and checking it against the original. He read the Odyssey, Pushkin’s verse epic Eugene Onegin and Home of the Gentry by Turgenev in Russian. At the age of 17, he was not only fluent in Swedish and Russian but also in French, English and German. The English romantics Wordsworth, Shelley and Lord Byron, his “favourite poet”, made a lasting impression.

Lord Byron, the “favourite poet”.

In the poem “You say I am a riddle”, which Nobel wrote during his first visit to Paris in 1851, you find an echo of this romantic idealism. The poem, with its 319 lines of poetry written in English, is largely autobiographical. It is dedicated to a “lovely girl”, too early “wedded to her grave”. It begins:

You say I am a riddle – it may be

for all of us are riddles unexplained.

Begun in pain, in deeper torture ended.

This breathing clay what business has it here?

Stockholm, Hamburg (1863-1873)

During the busiest periods of his life, Nobel was forced to put his literary interests to one side, especially at the beginning of his career when experiments, financial problems, constant travelling and a growing industrial empire absorbed most of his time. However, reading good literature was his main form of relaxation and he always took a book or two with him on his travels. One letter reveals that, even as late as at the age of 35, when some projects had gone awry, he considered abandoning business and his inventions and taking up writing for his livelihood.

Paris (1873-1891)

Nobel settled in Paris, the capital of culture, at the age of 40. “Every mongrel here smells of civilisation”, he noted with pleasure. Here he met Bertha von Suttner (later founder of the Austrian peace movement), a meeting which was to prove very important for Nobel, not because of the peace issue alone. When she first visited his home on Avenue Malakoff in 1876, Bertha was struck by his “well-stocked library, capable of satisfying the most divergent wishes”. Her visit was brief, but they maintained a lifelong intellectual friendship, mainly through correspondence. His discussions with Bertha were to prove stimulating – on literary matters as well. She never failed to send him her works with a friendly dedication: “From your dear friend and comrade-in-arms”, “a testimony of our friendship”. Reading her work may well have influenced Nobel’s own attitude to literature in “an ideal direction”. This could apply not only to her description of society and her anti-war novel Die Waffen nieder! (Lay down Your Arms!, 1889) – her “admirable masterpiece”, which he praised for its grand ideas and “charming style” – but also to works such as Ein Manuscript!(1885), where she reflected upon questions of a more private and aesthetic nature.

Victor Hugo (at the window) lived in this house on Avenue d’Eylau (now Avenue Victor Hugo), the same street where Alfred Nobel’s companion, Sofie Hess, lived.

Juliette Adam-Lamber, who maintained a literary salon, wrote books and published the magazine La Nouvelle Revue, was one of the few people whose company Nobel kept in Paris. He met Victor Hugo at her home and probably also younger writers like Pierre Loti, Paul Bourget and Maupassant. Both Bertha von Suttner and Nobel had contacts with the literary circle linked to the more academic magazine La Revue des Deux Mondes. It is remarkable that despite his busy life he was able to keep up with current literature, and at that time he systematically added to his library contemporary literature not only in French but also in English, German and the Scandinavian languages. He also collected the classics in beautifully bound editions, Musset, Tegnér, Shakespeare, Scott, Goethe, Schiller, all writers that he quoted readily.

Madame Bovary is being dissected by Flaubert.

“Zola sat on a pile of dung and spread a terrible stench”, he joked. Nobel apparently felt distaste for naturalism; however, he did appreciate the realism and psychological dissection in Le Père Goriot (Father Goriot) and Eugénie Grandet by Balzac, Madame Bovary by Flaubert and Maupassant’s sophisticated short stories. Among Norwegian writers he preferred Ibsen and Bjørnson (Nobel Prize 1903). His favourite Danish writer was the story-teller H.C. Andersen. Turgenev and Tolstoy were the Russian writers he valued. (There is no Dostoyevsky in his library.)

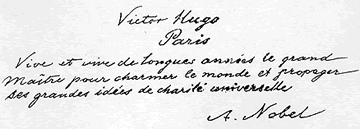

Among the French he most admired Victor Hugo, the pacifist and the idealist, who felt such compassion for “les misérables”, the social outcasts. Nobel was also invited from time to time to the aged laureate’s home; they lived close to each other near the Bois-de-Boulogne. On Hugo’s 83rd birthday in 1885, Nobel sent the Master the following telegram:

Vive et vive de longues années … (“Great Master, long may you live to charm the world and propagate your ideas about universal charity”).

Alfred Nobel’s note to Victor Hugo.

Nobel was sent Selma Lagerlöf’s Gösta Berling’s Saga by his niece, Ingeborg. To a friend he wrote: “The novel is highly original, and although events take an even more illogical course than in nature, as it appears to us, the style still possesses an appeal that cannot be praised too highly.” In 1909 Selma Lagerlöf became the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

A copy of Gösta Berling’s Saga.

Alfred Nobel and August Strindberg were in Paris at the same time in the mid-nineties. However, it does not seem as if the two ever met. Nobel acquired, amongst other works, Hemsöborna, Utopier and Le plaidoyer d’un fou by Strindberg. It is not known what he thought of Strindberg the writer, but his opinion as a professional chemist of Strindberg the alchemist can be gleaned from the discreet corrections of formulas he made in the margins of Strindberg’s essay Introduction à une chimie unitaire (Mercure de France, October 1895).

Viktor Rydberg was the Swedish poet he held in greatest esteem. Rydberg’s writing “denotes nobility of soul and beauty of form”, he wrote. In another context Nobel described himself in the words: “I am a misanthrope and yet utterly benevolent, have more than one screw loose and am a super-idealist, a kind of ungifted Rydberg, I digest philosophy better than food.”

San Remo, Paris, Bofors (1891-1896)

Nobel’s collection of books bears testimony to both the depth and breadth of his reading, even in fields such as philosophy, history, religion and the history of science. He was familiar with Voltaire and Rousseau, the philosophers of the Enlightenment. He studied positivism and Comte with particular fervour, Comte’s anti-religious and philosophical ideas about society corresponding to a large extent with his own. He also diligently inserted discreet pencilled annotations in positivistically inspired works such as G.H. Lewe’s History of Philosophy, Hippolyte Taine’s Les origines de la France contemporaine and Henry Buckle’s History of Civilisation in England, as well as in Gibbon’s worldwide success The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Albert Schwegler’s Geschichte der Philosophie and Karl von Rotteck’s Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, with its rapturous idealism and love of liberty. Voltaire, Gibbon and Taine were almost certainly writers who appealed to him with their wit and distinctly clear style. Likewise Spencer, the systematiser of the modern philosophy of evolution, appealed to him too. However, like the empiricist he was, he found Kant’s metaphysics harder to digest: “Kant’s style is so heavy that after his pure reason the reader longs for unreasonableness.”

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species can be found in his library – naturally, one would like to comment. Nobel’s criticism of religion and his ideas on the evolution of man indicate the strength of the impression made upon him by this work, by far the most revolutionary of its time. His notes in Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte by Ernst Haeckel, a contentious defence of Lamarck’s and Darwin’s theory of evolution, speak for themselves. Nobel’s philosophical thoughts on atoms, the cosmos and the development of the modern conception of the universe are based on Democritus, Giordano Bruno, Leibniz’s theory of monads and von Humboldt’s world-view. However, it must be emphasized that Nobel, an inherent sceptic, always read with a critical eye and reserve.

In 1891 Nobel was obliged to leave Paris. He settled in San Remo and in his old age, when he was in poor health, he was able to resume his writing. He had already started a socially critical novel before leaving St. Petersburg, I ljusaste Afrika (In Brightest Africa), where, in the guise of Monsieur Avenir, he sets out his political ideas, and also the draft of a longer novel, Systrarna (The Sisters), where he discusses faith and knowledge with the free-thinker Oswald and questions the divinity of Christ. In 1895 he produced the draft of a farcical satire, The Patent Bacillus, based on the dogmatism and bureaucracy he experienced in England during the Cordite Case. Sarcastically he notes: “Madam Justice has always had paralysis of the legs and therefore she has always been terribly slow, but now that seems to have affected her head as well, she appears to be too mad even for a madhouse.”

Beatrice Cenci (d. 1599), after Guido Reni.

In March 1896 Nobel wrote to Bertha von Suttner to say that he had completed a tragedy. “I have based my writing on the moving story of Beatrice Cenci, but I have dealt with it very differently from Shelley.” When it comes to the plot and the historical background he appears to have been influenced by the Italian Guerrazzi’s portrayal of Beatrice Cenci, which Nobel read in a German translation, pen in hand. After experimenting with a number of different alternatives, he finally called the play Nemesis. 100 copies were published at his own expense in Paris a few weeks after his death, but all copies – bar three – were destroyed in accordance with his family’s wishes. It was felt that such a weak drama could not honour the memory of such a prominent man. This assessment was probably not entirely unfair; the dialogue of the play seems stilted, its characterisation too black and white and the horrible revenge scenes so bizarre, that the work can hardly be described as tending towards the “ideal”.

Nobel was in many respects a man of the pen: he was continuously writing letters, noting down all kinds of fanciful ideas and plans for inventions, philosophising over the origin of the cosmos and the evolution of man, discussing questions of faith and knowledge, war and peace. When he died, he left an extensive collection of letters: business correspondence, letters from his brothers and other close friends and relatives and also copies of his own letters. At times he wrote twenty odd letters a day. Over the years he became a proficient correspondent, cleverly adapting language and style to the recipient. Bertha von Suttner describes the beginning of their correspondence in her memoirs: “Mr Nobel and I exchanged several letters. He wrote soulful and intelligent letters, but in a melancholic tone. He seemed to be unhappy, misanthropic, highly cultured, and to own a deeply philosophical conception of the world. A Swede, whose other mother tongue was Russian, he wrote with the same accuracy and elegance in German, French and English.”

In his private letters he liked to portray himself as a sickly old grumbler, ugly and unsociable. But they also bear testimony to a moving concern for his nearest and dearest, especially his mother and his brothers’ children. In other letters his words can seem very caustic. When his brother Ludvig asked him in 1887 whether he did not wish to contribute to a biography of the Nobel family, his reply was: “For me writing biographies is impossible, unless they are brief and concise, and these are, I feel, the most eloquent. E.g. Alfred Nobel – pitiful halfling, should have been suffocated by a humane doctor, when he made his wailing entry into life. Greatest merits: keeping his nails clean and never being a burden to anyone. Greatest defect: lack of family, a happy disposition and a good stomach. Greatest and only request: not to be buried alive. Greatest sin: not worshipping Mammon. Important events in his life: none.”

Nobel was obviously fascinated by language. In his youth his literary talents lay in poetry, later on in life in the aphoristic and self-reflective. Concise expressions, pithy observations, often spiced with pungent humour and merciless self-criticism, were his distinguishing features.

Nobel’s self-denial and misanthrophy were, however, balanced by a solidly grounded belief in progress. Technological inventions and scientific conquests would lead humanity forwards, and he seems to have believed that good literature could play a dynamic role in an “ideal direction”.

Alfred Nobel’s library can be found today at the Nobel Museum at Björkborn Manor, Bofors, Sweden. See http://nobelmuseetikarlskoga.se/index.php/home)

* Åke Erlandsson was born in 1938.

School of Education: Ph.Lic. in History of Literature, lecturer at the University of Umeå, Sweden, and at the University of Paris-Sorbonne (1971-73), School of Librarianship, chief librarian of the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy (1992-2001).

He has published inter alia: Litterära smakdomare (editor and co-author, 1987), Modern fransk prosa (1993), Alfred Nobels bibliotek: en bibliografi (2002). CD: Svensk Lyrik (co-editor and co-author, 1998). Internet: The Private Library of Alfred Nobel, Nobelprize.org.

First published 23 July 1997

Copyright © Åke Erlandsson, Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy 1997