Introduction

Alfred Nobel (1833-1896) – scientist, author and pacifist, but above all the inventor of dynamite and holder of 355 patents – shaped as a human being in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the Russian capital where different nationalities and cultures mixed and where science and literature developed in a dynamic interaction between Western European tradition and the aspirations of the Russian intelligentsia. Here are the roots of his international prizes – the Nobel Prizes – which made him world-famous after his death in 1896.

A young Alfred Nobel

A young Alfred Nobel

Early years

Alfred’s father Immanuel Nobel was an inventor and builder. When Alfred was five years old his father moved to St. Petersburg, where he set up an engineering factory. Immanuel’s wife Andriette and their sons Robert, Ludvig and Alfred joined him in Russia a few years later. Less than a year after her arrival in St. Petersburg, Andriette gave birth to a boy, Emil. After that she had another son and a daughter, but both died as infants.

Andriette Nobel neé Ahlsell

Andriette Nobel neé Ahlsell

After Immanuel arrived in St. Petersburg in December 1838, he became a successful manufacturer, inventor and designer of machinery. He landed a contract with a Russian general named Ogarev, who was interested in the Swedish inventor’s designs for sea and land mines, and with whom Immanuel went into partnership for some time.

Immanuel Nobel’s business flourished and evolved into a large mechanical engineering company, Fonderies & Ateliers Mécaniques Nobel & Fils, a name that reflected the predominance of the French language in Russian society at that time. Aside from sea and land mines, the company made machines for fabricating wagon wheels and turned out something as complicated as steam engines for Volga River steamboats.

The earliest central heating installations in Russia were manufactured in Nobel’s factories, and the first one was set up in his own house.

Education

In St. Petersburg, the Nobel family enjoyed a living standard far higher than they had experienced in Stockholm. But theirs was not a life of luxury. The Nobels lived in a single-story wooden house that gave an impression of bourgeois comfort.

The family invested in the education of the boys. All instruction was provided by private tutors in their home. Today this may seem peculiar and be viewed as a sign of high-bourgeois status, but this was not the case in St. Petersburg at that time. The Nobel brothers had a Swedish tutor – Lars Santesson, Master of Arts – who taught them Swedish language and history, but also provided them with a broad knowledge, including world literature and philosophy. They also had a skilled Russian teacher, Ivan Peterov who among other subjects taught them the fundamentals of mathematics, physics and chemistry.

They learned five languages fluently – aside from their native Swedish they also spoke Russian, English, French, and German. Robert and Ludvig became engineers, while Alfred studied chemistry. His chemistry teachers were Professors Nikolai N. Zinin and Yuli Trapp. Professor Zinin later drew Alfred and Immanuel’s attention to nitroglycerine.

Literature and philosophy

Letters from this period paint a picture of a precocious, unusually intelligent but sickly and brooding young man who preferred solitude. Alfred had strong literary interests and was particularly fascinated and influenced by English literature, especially by the English poets, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

He readily adopted Shelley’s attitude to life as well as his extravagant idealism, his all-embracing love of mankind, his pacifism, his radicalism and his somewhat chaotic and fanatical “atheism.” At the age of 18, Alfred wrote a first version of an autobiographical poem of 425 lines in excellent English – “You say I am a riddle” – that gives an indication of his life and thoughts during the years of his otherwise little-known childhood and early youth. A young girl is mentioned, who “good and beautiful,” looked up to me, to me alone for love … but “Had stronger claims – she’s wedded to her grave.” The poem ends by saying that again he is alone in life. Alfred destroyed most poems of his youth. In his later poems and literary works we can always trace his ideas back to his youth and experiences in Russia, i.e. the poem “Night-thoughts” from around 1875, in which he meditates upon the riddles of life, upon God and eternity, but also expresses homage to Newton and the natural sciences.

Alfred Nobel’s interest in philosophy started early with the great philosophers, from Plato and Aristotle onward. While still in St. Petersburg he improved his French by translating Voltaire into Swedish and then back into French; after which he would compare the final version with the French original. To increase his vocabulary, he memorized dictionaries page after page, perhaps to compensate for his weak physical powers.

Travels abroad

Alfred Nobel never attended any university, nor did he obtain any degree. His tutorial instruction came to an end as early as 1850. While his older brothers Robert and Ludvig were busy working in the family engineering enterprise, Alfred was sent at age 17 out into the world on educational travels, first to Paris, where – at the recommendation of his chemistry teacher, Professor Zinin – he worked in the laboratory of the famous Professor Jules Pélouze. Here he came into contact with the Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero, who had discovered nitroglycerine in 1847. Nitroglycerine possessed violent explosive power, but no one had devised a solution regarding how to control this highly dangerous substance.

Alfred’s education continued in the United States where he studied the latest technological advances. He met with John Ericsson, his father’s countryman and contemporary who had arrived in America the year after Immanuel reached Russia and whose interests and inventions largely coincided with the Nobel company’s activities in St. Petersburg.

Alfred (left) and Ludvig Nobel photographed in St. Petersburg, probably around the end of the 1840s.

Alfred (left) and Ludvig Nobel photographed in St. Petersburg, probably around the end of the 1840s.

St. Petersburg in the 1850s

Returning from his foreign travels in 1852, Alfred joined his two brothers at their father’s factory in St. Petersburg. Alfred often suffered from delicate health. Combined with hard work, this led him to fall ill in the summer of 1854 and he traveled to the Bohemian spa town of Franzenbad to take the waters.

Together with his father, Alfred had understood the enormous potential of nitroglycerine as an explosive and tried to develop a form that was less hazardous and easier to handle. In testimony during one of the American patent cases that Alfred was involved in many years later, he explained how he and his father had become interested in nitroglycerine. He was asked:

“Do you know of any one before you having experimented with nitroglycerine?”

His answer:

“Yes, Sobrero who discovered it, also discovered that it was explosive. Professor Zinin and Professor Trapp in St. Petersburg went a step further in conjecturing that it might be made useful and called the attention of my father to it, who was then engaged in making torpedos for the Russian government during the Crimean War. My father tried it, but could not get it to explode.”

The next question:

“When did you first experiment with nitroglycerine, and what did you do?”

Alfred Nobel’s answer:

“The first time I saw nitroglycerine was in the beginning of the Crimean War. Professor Zinin in St. Petersburg exhibited some to my father and me, and struck some on an anvil to show that only the part touched by the hammer exploded without spreading. His opinion was that it might become a useful substance for military purposes, if only a practical means could be devised to explode it … My father tried to explode it during the Crimean war, but completely failed to do so … My father’s later experiments with gunpowder mixed with nitroglycerine were all on a small scale.”

The early 1850s were golden years for the Nobel family. In 1853, Immanuel was presented at court and awarded Tsar Nikolai’s Imperial Gold Medal “for diligence and creative skill in Russian industry,” a rare distinction for a foreigner. After the Tsar’s death in 1855 and the conclusion of the Crimean War under the Treaty of Paris of March 30, 1856, the new government of Russia disregarded the promises for orders made by its predecessor.

Immanuel Nobel painted this illustration of the tests he conducted in 1841.

Immanuel Nobel painted this illustration of the tests he conducted in 1841.

Immanuel Nobel’s financial reversals accumulated. The Russian government favored foreign suppliers at the expense of domestic ones, and Nobel’s St. Petersburg factory was left to its fate. Alfred was sent to London and Paris in an attempt to raise money to save his father’s business, but few investors wanted to risk money in Russia after the Crimean War. The sons saw the end coming, but Immanuel probably remained hopeful to the last. In 1859 it was all over. For the second time in his industrious life, Immanuel Nobel faced bankruptcy. Completely ruined, he and his wife and youngest son Emil left Russia in the summer of 1859.

When their parents returned to Sweden, the lives of the Nobel sons entered a new phase. Ludvig, a mechanical engineer, was appointed by the creditors to administer and phase out the business of Atéliers Mécaniques Nobel et Fils. Robert and Alfred stayed on with Ludvig in St. Petersburg. Ludvig revived a portion of the business, naming his company the Ludvig Nobel Mechanical Factory. Together with his brother Robert, years later he built up an oil empire known as the Brothers Nobel, or Branobel, based on oil deposits in Baku on the Caspian Sea.

Experiments

Alfred devoted himself to the mechanical and chemical experiments that had occupied him previously, but that had been interrupted by illness and journeys undertaken for his father. The first visible results of Alfred’s experimental work were his first three patents, originated in St. Petersburg: a gas measurement apparatus in 1857, an apparatus for measuring liquids in 1859 and an improved design for a barometer or manometer in the same year – none of these of any great general importance.

Alfred also continued the nitroglycerine explosive experiments begun by his father, first working alone in St. Petersburg and later together with his father in Stockholm. The approaches that Immanuel had used proved to have been completely wrong. With his father’s failure in mind, Alfred tried entirely different methods for using nitroglycerine as an explosive.

In May or in June 1862, in the presence of his brothers Robert and Ludvig, he succeeded for the first time in causing nitroglycerine to explode, and, indeed to do so under water. He had poured the substance into a glass tube, which he had stoppered firmly. Then he placed the test tube in a zinc container that he filled with gunpowder. The other tube was stoppered at both ends, and a fuse was introduced into the powder. He lit the fuse and threw the whole contraption into a canal, whereupon a sharp explosion and a substantial water spout hurled upwards, showing that the nitroglycerine had been completely exploded. During the winter 1862-1863 Alfred set off several successful explosions on the frozen Neva River.

A detailed study of the various stages of submerging the Nobel mines.

A detailed study of the various stages of submerging the Nobel mines.

Immanuel had struggled with the same problems, and when he heard about Alfred’s experiments he accused his son of virtually stealing his discovery. While Alfred was a scientifically trained chemist, the older Nobel was a mere amateur. Alfred set out his position in a letter, after which his father admitted that he had been wrong. Here are some extracts from the letter:

“My Dear Father,

…

When you first wrote to me in Petersburg, you gave me to understand that the new explosive powder (chlorate powder) was a fully worked-out invention, and that it was twenty times as powerful as ordinary powder…. At your request I then came to Sweden, and found that your statements had been based upon an inconclusive experiment in a lead pipe. The result was a complete fiasco…. Meanwhile, in accordance with Ludvig’s sensible advice, I had decided not to discredit myself or us by recommending chloric acid powder, and I began to work on pyroglycerine in Petersburg on my own account. I did, in fact, succeed in producing astonishing results with experiments on a small scale under water…. I arrived at a principle which I had already suspected, and which is entirely different from that which underlies your use of glycerine powder, the principle being that if a small amount of pyroglycerine be rapidly caused to explode, the shock and the heat generated will communicate the explosion to the whole mass.”

As a result of the straightforward manner in which Alfred had cleared up the situation, friendly relations between father and son were restored – even if it took some time.

Back to Stockholm in 1863

In 1863 Alfred left St. Petersburg and moved to Stockholm to join his parents and younger brother and work in his father’s laboratory at Heleneborg on the outskirts of Stockholm. His relocation to Sweden marked the definitive end of his period in St. Petersburg. He would return once in 1883 to visit his brother Ludvig and to take a closer look at the Brothers Nobel oil company, which was headed by Ludvig and in which the three Nobel brothers were the main shareholders.

The introduction to Russia of Alfred Nobel’s invention, dynamite, came only in 1877 when Alfred received a ten-year patent “to produce new solid explosive substances from liquid explosives.” In December the same year, the Diet (Parliament) of Finland, then an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia, approved the introduction of dynamite. Alfred Nobel never had his own dynamite factory in Russia. Nevertheless, a large share of Alfred Nobel’s fortune came from his investments in Russia – more than SEK 5 million out of a total of SEK 33 million in his estate, which was an enormous sum at that time.

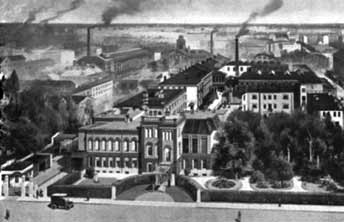

The Brothers Nobel (Branobel) factory, office and residence located near the Samson quay in St. Petersburg.

The Brothers Nobel (Branobel) factory, office and residence located near the Samson quay in St. Petersburg.

In none of the many letters Alfred Nobel left after his death did he ever mention his own situation in Russia, nor did he ever express his real feelings about that country.

by Birgitta Lemmel*

* Birgitta Lemmel was Head of Information of the Nobel Foundation in 1986-1996.