by Åke Erlandsson*

“Thus it [the child] grew and developed into a thinking, sentient being with an inner world of poesy that no tyranny could extinguish. The lyrics of our wonderful poets became for me entrancing and consoling echoes of the spiritual world of feeling and thought.”

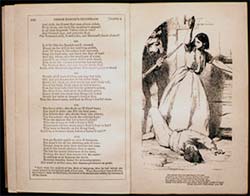

Beatrice Cenci in Alfred Nobel’s tragedy Nemesis

Introduction

Loneliness, thirst for love, reflection on the meaning of life and the origin of the universe provide the fundamental themes of Alfred Nobel’s autobiographical and melancholically inclined poetry, which consists of little more than a handful of works in more or less finished manuscript form. The longest and most complete are written in English, in blank verse. The poems, including those written in Swedish, span a period from his youth to his later years. These essays in lyricism are the fruit of long and faithful acquaintance with the Romantic poets, particularly the English Romantics, Shelley and Byron. Nobel was an occasional poet: he mainly resorted to the pen in order to divert his thoughts when he felt lonely, was tired of business and plagued by intrigues. Then poetry was a source of energy and inspiration. In his personal and contemplative poetry we encounter a little known aspect of this otherwise famous inventor and endower of prizes. With one or two exceptions, these poems have remained concealed in Swedish archives for the best part of a century. In establishing the text, I have tried to include the corrections that Nobel himself made to his manuscripts. As a rule, the latest version is the one used here.

Why publish poems that Alfred Nobel himself never let publish, some, moreover, that were never completed? We also know that he guarded his integrity jealously, and that his shyness and reticence were legendary. There are however some cogent reasons for making them public. One is that he himself took out some of his poems to send to outsiders for their assessment. Another is that although he was highly self-critical, he was not alien, as his letters show, to the idea of publishing one or two of his poems, if only for his own pleasure. Although the brilliance that surrounds the name of Nobel has intensified with the years and the Nobel prize awards, the man himself, the humanist, has become obscured, and indeed seems increasingly enigmatic. His poems offer no solution to the mystery, but they do bring us closer to this remarkable, many-faceted man who at the end of his life, when he wrote his tragedy ‘Nemesis’ (1896), noted: “There is a philosophy of both feeling and thought”. Those who want to find out more about his emotional and intellectual life will find one opportunity here. In principle, lyric poetry is a genre of self disclosure.

The play ‘Nemesis’ was written by Nobel during the last year of his life.

It seems natural to introduce the poet and cosmopolitan Nobel to an international audience. He wrote his most significant poems not in his native language, but in English. It is also important to emphasise in this context that they were drafts. There would be little point in comparing him with his brilliant exemplars. In a letter (undated) addressed to a certain Mrs Granny he attached his poem ‘Night-thoughts’ for her appraisal and added: “I have not the slightest pretension to call my verses poetry; I write now and then for no other purpose than to relieve depression, or to improve my English. Do you think I may, after a good deal of future exertion, improve so far as to write a tolerable letter in your language? ‘That is the question’; to which I might add many more, which Hamlet possibly thought, but never uttered.” The self-deprecation paired with the acerbic humour is unmistakeably characteristic of Nobel. The comment also testifies to considerable self-insight.

St. Petersburg 1842-1863

The largest category in Nobel’s private library of almost two thousand works comprises literature. The English Romantics form the largest contingent of poets, in particular in early editions. What poetry did he read in his youth in St. Petersburg? It is difficult to give an exact answer. Many of the books seem not to have been read. Well used works, often with notes and other personal reactions, disclose more or less intensive scrutiny. But even in these cases it would be difficult to determine when they were read. The year of publication combined with biographical information can sometimes help to establish dates. One example can be found in an early Russian edition of Pushkin’s collected works (1854) with Alfred Nobel’s signature. In the volume containing ‘Eugen Onegin’, the verse narrative inspired by Byron, the young Alfred, not yet totally proficient in Russian, has assiduously underlined words and at times provided English translations. There is a great deal, therefore, to suggest that he read ‘Eugen Onegin’ as a young man in St. Petersburg.

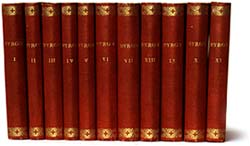

Lord Byron himself is abundantly represented by ‘The Works of Lord Byron’ (1826) in eleven small, red, gilt-edged volumes. The first of them contains a poem written in French by a certain Harriett:

| Qu’ils obtiennent dans mon absence Un doux regard de souvenir; Car de mon cœur plein de constance Vous ne pourrez jamais sortir.Harriett |

We do not know who this Harriett was. It is also unclear whether this affectionate dedication was addressed to Alfred and whether he already owned the handsome small volumes as a young man.

The eleven volumes of ‘The Works of Lord Byron’.

Traces of Nobel’s reading can also be found in ‘The Poetical Works of Lord Byron’ (1861) and in the five-volume edition of ‘The Works of Lord Byron’ (1866). Alexander Büchner’s biographical short story ‘Lord Byron’s letzte Liebe’ (1862) also formed part of his reading in this period. The bulk of Nobel’s literary works in English consists of the inexpensive series published by Tauschniz in Leipzig entitled Collection of British Authors, represented for instance by early editions of Thomas Moore (1842), Burns (1845), Coleridge (1860) and Wordsworth (1864).

What place did Shelley occupy in Nobel’s library? It indeed contains four copies of ‘A Selection from the Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley’, but all published as late as 1872. These editions, the drama Cenci in particular, would acquire renewed significance later when Nobel was working on his tragedy ‘Nemesis’. There is, however, reason to believe that while still a teenager in St. Petersburg Nobel had read and was familiar with Shelley’s works.

Alfred Nobel the Poet

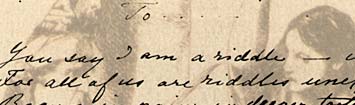

Nobel’s letters reveal that he destroyed a great deal of youthful poetry. One of his earliest known essays in poetry is ‘A Riddle’, which begins with the words “You say I am a riddle”. In a manuscript version he has noted in pencil “écrit par moi en 1851”. He was then 18 years old and the poem seems to have been written during his first stay in Paris, the outcome of a romantic disappointment.

|

Robert Nobel, his eldest brother wrote a letter on December 4th, 1859, from St. Petersburg to his fiancée Pauline. He wants to tell her something amusing about Alfred (26) who had begun to take lessons in English “which caused us all no small amazement, the more so as he both speaks and writes it extremely well. I have often heard him declare: ‘I will probably be the only member of the family to marry into money’.” Alfred had also confided in Robert that “he has been admired by the ladies for his great progress and for the verses he writes in their honour. Poor Alfred! He is ready to slave away night and day for a few unctuous phrases that flatter his vanity. Anticipated praise is the reason for him to take these lessons, but I assume that as his skill with languages is his chief accomplishment and he will now find himself in a position to demonstrate his great proficiency to the fairer sex, he hopes that his verses will win him some rich and beautiful young woman. – Recently however, I have heard no mention of a rich marriage, which leads me to assume that young women are not so easily ensnared as his vanity.”

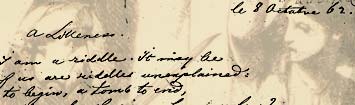

In October 1862, Alfred (then aged 29) sent an emotional letter in French and his poem A Likeness – a somewhat revised version of A Riddle – to “Mademoiselle” Olga de Fock who was living in the manor house at Maanselkä in Karelia. He included G.H. Lewes’ novel Ranthorpe. Alfred is upset about a rumour claiming that he has time to write poetry. This canard probably emanates, he asserts, from a “mademoiselle de Lisogoub”. In his defence he writes: “je n’ai rien écrit, pas même une ligne dans un album depuis l’âge de 20 ans. […] La Physique est mon domaine, non la plume. En outre c’est une grande difficulté que de composer dans une langue qui n’est pas la nôtre. Cependant, puisque il le faut, essayons. Vous avez dit autrefois que je suis une énigme. Faute de mieux je Vous en donne le mot dans les lignes ci-incluses. Je Vous épargne la rime qui n’est qu’un travail mécanique et ne sert, le plus souvent, qu’à déguiser la platitude des idées.” [“I have written nothing, not even a line in an album, since the age of 20. /…/ Physics is my domain, not the pen. And moreover it is extremely difficult to write in a language that is not our own. Nevertheless, as it is required, the attempt shall be made. You once said that I was a riddle. For lack of anything better I return the epithet in the lines attached. I have spared you rhyme, as it is merely a mechanical device and frequently serves no other purpose than to conceal the platitude of thought.”] What is noticeable here is his opinion that rhyme is an unnecessary adornment that often serves to conceal banality of content. This is a subject we shall return to in the context of Night-thoughts.

Ranthorpe is a Bildungsroman, described in his letter as “un joli petit Roman qu’il vaut la peine de lire”, which does not lack interest in this context. Its protagonist, Ranthorpe, is a melancholic, self-taught young man, animated by romantic ideas of authorship and a passion to take life seriously. A fellow-soul in other words. The omniscient author makes frequent references to Shakespeare, Coleridge, Shelley and Byron, that is to say some of Nobel’s own favourites.

Some months later Nobel obviously sent an otherwise mysterious poem in blank verse to a certain Mrs Isherwood, who responded in January 1863: “I have read with great care & much pleasure Mr [sic!] Lisogoub’s lines, – they are very fine, full of deep thoughts, well expressed, – a mournful music pervades the whole composition which must speak to every feeling heart, particularly to those which have suffered here below. – I pay it, but a just tribute, saying, it ought in my opinion to be placed among our best blank-verse productions. – It is without doubt, an original work & I think in this case Mr Lisogoub cannot be accused of plagiarism. The man who wrote those lines, my dear Mr Nobel, is no mean rival, ‘but faint heart never win fair lady’. You have all my sympathy, the lady for whose favour, two such clever men contest, must indeed be fair gentle & good. The idiom here & there is not quite English which I will point out to you, when you do me the pleasure of spending the evening with me.” Who was Mr Lisogoub (which in Russian means “Foxlip”)? A pseudonym for Nobel?

At the end of her life, the mademoiselle A. de Lisogoub referred to above, the rumourmonger, was to remember the young Alfred’s bent for poetry. In a letter dated May 8th, 1896, she writes: “Vous m’apparaissez toujours dans mes souvenirs, tel que Vous étiez en Finlande, aux idées larges et pleines de poésie, éclairées par une grande force d’intelligence.” [“In my memories you always appear as you were in Finland, animated by expansive ideas, full of poetry, illuminated by a powerful intelligence.”]

Stockholm 1863-1865; Hamburg 1865-1873

| “But those who have written poetry must continue to do so: the desire is irresistible.” |

Robert, the poet in Nobel’s unpublished drama

Ett fantasiens offer (‘Victim of Imagination’)

During the most hectic phases of his life, Nobel was obliged to put his literary interests aside, particularly at the beginning of his career when experiments, financial problems, incessant travel and a burgeoning industrial empire devoured the bulk of his time. However, he had not entirely abandoned the idea. During a stay in Hamburg, in the middle of his life, he even contemplated a change of career. In the autumn of 1868 the inventor of dynamite had encountered setbacks in the form of accidental explosions that led to adverse newspaper articles and the threat of bankruptcy. Fatigued and tormented he writes to Robert that he wants to renounce everything related to business: “I may possibly need to earn my living by the pen. […] That I am not completely convinced of my own inadequacy may perhaps be excused by the extremely favourable comments on a few minor poems in English I have received recently from an English scholar and writer, who, as I am completely unknown to him, can hardly be suspected of flattery.”

The Englishman referred to was a priest, C. Lesingham Smith, himself an amateur poet. In a letter dated October 6th, 1868, he had expressed to Nobel the following opinion: “The thoughts are so massive & brilliant, if not always true, that no reader can for a moment complain of dullness, nor miss ‘the jingling sound of like endings’ any more than in Paradise Lost. I have read it not only carefully but critically, as you will see by the annexed remarks. I should have considered it a marvellous production for an Englishman, but the marvel is increased hundredfold by the fact of its author being a foreigner. I have industriously hunted out every grammatical error & false idiom, & you will see how small the amount of these is. There are not half a dozen mediocre lines in the whole 425. […] If you can write such a poem in the English tongue, what could you not do in your own, especially if you bide your time, as Milton did, till advancing years shall have enlarged your experience, shall have softened down asperities of thought, & given you a perfect command over words?”

Nobel paid careful attention to Lesingham Smith’s criticisms in later versions of A Riddle. Their correspondence reveals that he had destroyed a “hecatomb” of youthful poems. He also wrote out a shorter Swedish version of the poem.

Paris 1873-; San Remo and Paris 1891-1896

Another important moment occurs in the autumn of 1875, when Alfred had for the first time met and paid court to Bertha von Suttner. Almost twenty years later, in March 1896, he writes to his friend and confidante: “N’ayant pu m’occuper plus sérieusement pendant ma maladie récente, j’ai écrit une tragédie. Je viens de la terminer sauf à remanier par-ci par-là. J’ai tiré le sujet de l’histoire si émouvante de Beatrice Cenci; mais je l’ai traité tout autrement que ne le fit Shelley.” [“As I was unable to undertake anything more serious during my recent illness, I have written a tragedy. I have just completed it, apart from one or two changes here and there. As my subject I took the moving story of Beatrice Cenci, but my treatment is quite different from Shelley’s.”]

Nobel appreciated Shelley’s idealism and love of liberty.

Bertha, agreeably surprised, answers that she is convinced that Nobel’s tragedy is well written. At the same time she remembers his unpublished essays in poetry that she had been shown two decades earlier: “je n’ai pas oublié la beauté et l’élan des vers que vous m’avez donnés à Paris”. [“I have not forgotten the beauty and the fervour of the poems you gave me in Paris.”] Bertha returned to the subject in her memoirs: “Seine Studien, seine Bücher, seine Experimente – das füllte sein Leben aus. Er war auch Schriftsteller und Dichter, aber hat niemals etwas von seinen poetischen Arbeiten veröffentlicht. Ein hundert Seiten langes Poem philosophischen Inhaltes, in englischer Sprache abgefasst, gab er mir im Manuskript zu lesen – ich fand es einfach prachtvoll.” (Memoiren, 1909). [“His studies, his books and experiments – they occupied the whole of his life. He was also a writer and a poet but he never published any of his poetic works. He gave me the manuscript of a hundred-page poem, written in English – I thought it was simply magnificent.”]

A hundred-page poem? Nothing of this kind has been preserved and she was presumably referring to several poems, for example The Riddle and Night-thoughts in their more polished form.

In 1895 Nobel drew up a list of his scientific and literary projects. In a category headed “Literature and Poetry” he records 14 titles, including drafts for novels, dramas and lyric poetry, this latter genre predominating. The list also reveals, which is interesting, that even late in life he had a number of literary projects in mind.

Everything suggests that the young Alfred, at the most malleable stage of his life, encountered in his reading the great Romantic poets, in particular those writing in English. He was to foster this deep interest for his entire lifetime.

Motifs and Themes

A Riddle exists in four versions, three written by hand and one in typescript. They are all based on a version from 1851 that has since disappeared. The three handwritten versions can be dated approximately to the period 1862-1875. The typescript version is considerably later. Apart from the varying length and the personal dedication in the version entitled A Likeness there are no major differences in theme between the four. One main theme, the fundamental existential one, is already stated at the outset: the mystery of life and its meaning. Related themes involve love, loneliness, human vanity and egoism. The ‘I’ of the poem confides in a ‘you’– a woman who has described him as a riddle: “You say I am a riddle”. He depicts his early childhood, afflicted by illness and overshadowed by death, the alienation of his boyhood (“a pensive looker-on”), the lofty ideals of youth (“my ideal life”) and the mockery of its dreams, his encounter with love (“a lovely girl”) and the tragic death of his beloved.

The confrontation of dream and reality is a constant motif in Nobel’s poetry. This applies not least to his romantic conception of love: a dream of a non-sensual “pure love” and unswerving loyalty. Some would perhaps describe it as Victorian dissimulation, others as high-flown and unrealistic. Be that as it may, the disappointment is undeniable. A recurring message is noli me tangere!

|

What distinguishes A Likeness, written in the autumn of 1862, from the three later versions is that it is less polished and also that it has a personal addressee, “Mademoiselle” Olga de Fock. In the letter that accompanied the poem, Alfred refers to a remark that the young lady is said to have made: “Vous avez dit autrefois que je suis une énigme”. The concluding misanthropic lines of the poem consists of his rejoinder to her utterance:

| I’ve lost my faith in all that colours life, I’ve lost my trust to serve my fellow-men, And stand a wreck – I think you know me now, And if you don’t the riddle can’t be solved. |

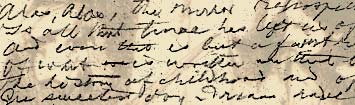

Alas, Alas. The manuscript page and the handwriting indicate that Nobel wrote this lyrical fragment of four rhymed couplets at the same time as he drafted “En gåta” (a Swedish version of A Riddle), at a guess sometime in the 1860’s. It is a melancholy, retrospective poem, and the motif of the daydreamer’s longing for an Aladdin’s lamp in the concluding line can be interpreted as the poet’s unavailing desire for creativity and love.

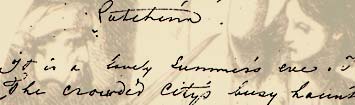

Gatchina – this fragment is presumably an early draft of Canto I. Gatjina was the summer residence of the Russian Czar, about three miles outside St. Petersburg. – The poet has withdrawn from the bustle of the city to the tranquillity of the countryside, where the ruins recall the glorious past. He reflects on the brutal progress of history but the serenity also calls to mind a youthful romance – “a lovely child”.

|

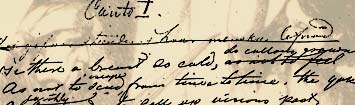

Canto I was most probably composed somewhere around 1863-1864. Nobel was then 30 and living in Stockholm. The poem consists of almost a thousand lines of verse, fifty-one manuscript pages full of deletions and amendments, with some words and lines that are difficult to decipher. It actually has no title. It was customary to divide long narrative poems into cantos, as in Shelley’s The Revolt of Islam or Byron’s Childe Harold, and Nobel’s heading presumably indicates that he intended to continue with Canto II, III, etc, so that, despite its length, the poem was never concluded. Towards the end he sighs in resignation: “This poem lengthens”.

Its main theme is poetry and the blessings that it brings. Who can be so callous and unfeeling that the vision of the beauty of nature and of man does not imbue him with religious awe and poetic feelings? Canto I begins with admonitory questions of this kind accompanied by examples and personal experiences.

The long poem is a lofty paean to poetry, an attempt to capture its essence. Its structure takes the form of various thematic categories or suites: poetry of the day, the night, of love, of life, of charity, of dreams. Each suite is exemplified from personal experience. The poem is addressed to the beautiful and virtuous Alexandra that he once paid court to (Alexandra , a “soulful beauty”, is also one of the characters in the draft of Nobel’s proposed novel Systrarne (“The Sisters”). Poetry is the most elevated form of language, as it is capable of endowing life with new meaning, of raising us above what is trivial and transitory. Poetic feeling is important for our development into moral, sentient, responsible individuals.

Some personal allusions and historical references date the poem. The poet remembers St. Petersburg: the river Neva flowing beneath his feet, the Peter and Paul fortress whose walls once rang with the screams of the tortured; the Winter Palace, “that school for sycophants and prostitutes” in the time of Catherine the Great.* The ruling Czar is the reformist Alexander II; great hopes are placed in a now twenty-year-old son, “a young prince born to the greatest power”. The narrator, now aged 29 in the poem, recalls his painful and joyless childhood:

| […] At twenty-nine, When I retrace the current of my years, I scarce can find a day without sting, The joys of Childhood swallowed up by Illness |

A few lines express Nobel’s indignation over the slaughter taking place in the American Civil War:

| […] Do we not see to-day Our brethren on the other side th’Atlantic Butchered, for what? Can Lincoln tell the why? |

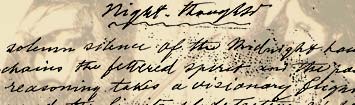

Night-thoughts, also entitled “Wonder”, exists in a manuscript and a typescript version. Their contents are identical apart from the final 28 lines in the manuscript version from around 1875-1885. The typescript copy is later. In the poem, the author develops the metaphysical issues raised in A Riddle and Canto. The silence of midnight allows unfettered fancy to soar beyond the limits of what can be seen and understood: the poet reflects on the mysteries of life and creation, on the essence of God and the miracle of nature, on the forces that bind atoms and direct the course of stars and planets. Reason, he concludes, sets firm limits to the existence and essence of God, but not thought and imagination, whose extent is infinite. The infinitely small reflects the infinitely large; the atom, like the dewdrop, reflects the universe. Everything is interconnected and “cooperates”.

Here Nobel presents us with examples of a more resolved view of the world. Among his favourite philosophers are Giordano Bruno, Leibniz and Spinoza. He rejects the credo of the atheists and the clergy’s “nursery tales”. Nobel the scientist can be recognised from the choice of metaphors and concepts. Here he is more stringent and concise than in A Riddle and Canto. Moreover he uses rhyme, which as a young man he rejected as unnecessary adornment. In the letter to Mrs. Granny referred to earlier he explains apologetically: “When I penned the lines which I here enclose for your kind and forbearing perusal, I scarcely knew how difficult it is to make blank verse readable. Rhymes form an excellent varnish for metrical nonsense, and to rhymes I should therefore have had recourse. As it is I have probably coupled blank sense and blank verse into a union of unparalleled dullness. If so, please consign the manuscript quickly to the fire: it will save you some trouble, and me some blushes.” Self-deprecation and acerbic humour are, as has been pointed out, part of Alfred Nobel’s signature.

Night-thoughts (the title taken from Edward Young?) is an ardent eulogy of “Thou wondrous Newton!”, the contentious scientist whose pioneering findings had demonstrated the forces of attraction and repulsion that govern the orbits of the planets as well as terrestrial phenomena. Indirectly, however, it is also a tribute to the natural philosopher and the mystic who saw the presence of God in Nature. These ideas – that everything is interrelated and that the workings of Nature inescapably take the form they have – also touch on those ventured by Spinoza in his day. In his “philosophical letters” (unpublished) Nobel refers to the Dutch philosopher, whose ideas were close to the conception of God and the pantheism expressed in Night-thoughts: God is an impersonal, all-embracing power manifest in the wonders of nature and in the orbits of the heavenly bodies as well as in the world of human thought, where idealism and materialism merge in mystic union. Nobel’s library includes a copy of The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope (1876), and we can assume that he was familiar with the frequently quoted couplet: “Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night / God said, ‘Let Newton be!’ and all was light.” It is not unlikely that Camille Flammarion’s Astronomie populaire (éd.1881) provided more up-to-date support for the cosmological excursions and viewpoints adopted in the poem.

Traces of Shelley and Byron

It has already been pointed out that Shelley and Byron were among Nobel’s favourite authors from his youth onwards. Words with poetic or archaic ring found in both the English Romantics can be recognised in Nobel’s poetry: thou art, didst, couldst, thee, thy, thine, Alas!, ere, budding blooms, fading leaves, fain would I, ideal beauty, I ween, gaze, kindred, unfathomable, “this world of woe”, etc. A line from Shelley, “And solemn midnight’s tingling silentness” (in The Spirit of Solitude), may be echoed in Nobel’s opening “The solemn silence of midnight hour” (in Night-thoughts). Shelley is only referred to once in Canto,

| […] Shelley says the greatest poet Is yet to come – he’s wrong – the greatest lives From all eternity: his works fill up The infinite of space […] |

There can be no doubt that Nobel applauded Shelley’s indictment of the church and all forms of abuse of power and that he was more than capable of appreciating his high-minded tone, his idealism and love of liberty. This was also true of Shelley’s unrhymed blank verse and his belief in the redeeming powers of poetry. But it was the colourful Lord Byron, with his biting self-irony, verbal pyrotechnics and high spirits, who was his favourite. Bertha von Suttner tells us that Byron was his “Lieblingsdichter”. Nobel was familiar with the verse epics Childe Harold and Don Juan. The traces are unmistakeable. In Canto he refers several times to Byron: he laments his inability to paint with the same “beauty-teeming pen” as the master and he even comes to the defence of the scandal-tainted lord:

| Such men of late have met with less Contempt Since Byron’s genius stooped to hallow Vice. But let us not mistake – his lofty soul Was drained of Pleasure not by lust but thought; His shapes ideal had such heavenly forms, The love he offered was so pure, so deep, He could not find the like […] |

In the draft of Nobel’s projected novel Systrarne (“The Sisters”) there is mention of “Byron’s ardent words” and of sensuous love with references to the comic epic Don Juan.

In his poetic travelogue Childe Harold Byron dealt with themes that we also find in Nobel’s poems: unhappy childhood, alienation, the desire for liberty, the thirst for love, lassitude, human folly, injustice and the abuse of power. Metaphors link remote and familiar objects. Natural and spiritual, concrete and abstract are characterised and personified in terms such as “Nature’s hand”, “Nature’s charms”, “Time shall tear thy shadow”. Or else they are embodied in antithesis: “Day and Night contending”, Heaven and Earth, Virtue – Vice etc. We encounter exclamations and appeals such as “art thou soul of my thought”, “match me, ye climes”, “Ye stars which are the poetry of heaven”… We find the words and phrasings of the typical Byronic hero: broken mirror, dregs, freeborn, lofty, nobler aim, paltry price, save where, selfish grief, sneer and so on. But there are even special indicators like houris, Bedlam, Mammon, unmoved, wormwood, “callous grown”, “coffined clay”; or sentences “great Nemesis!” , “honied lies of rhyme”, “revel ‘midst the crowd”, “What matters where we fall to fill the maws of worms” (cf. Nobel’s A Riddle, Canto). There are also contractions: o’er, o’erflow, ne’er, whate’er, etc. Rhetorical formulae and asides: “Now to my theme”, “But this is not my theme”, “But I am digressing” and “Away with these!” All of these have correspondents in Nobel’s works – as do “the spleeny thoughts”, the melancholy.

Alfred Nobel’s poems echo themes found in Lord Byron’s works.

How should we view Nobel’s essays in poetry? We remember his own self-criticism: “I have not the slightest pretension to call my verses poetry; I write now and then for no other purpose than to relieve depression, or to improve my English”. It would be unfair to describe him as an epigone of Byron or Shelley. He is by no means a slavish imitator, but he borrows images and tones that correspond to his own mood and view of life. It is more a case of dialogue and “creative reception”, albeit with no great aspirations from his point of view. And comparable in no respect to his lofty exemplars. Nobel’s familiarity with literature almost certainly provided inspiration from other writers as well, although less obviously. In spite of everything, his poems have an unmistakeable voice, their own style and their own themes. They are permeated by his presence and genuine emotion, and they have explicit autobiographical and philosophical points of contact. The world view we encounter is both that of the scientist and the humanist. This applies in particular to Night-thoughts.

Expressing his ideas and feelings in “in the English tongue” – the language of Shakespeare, Shelley and Byron – seems to have come naturally to the linguistically gifted Nobel. But it can also be seen as a form of homage to the poets he had already become attached to in his youth.

A page from Childe Harold by Lord Byron.

After his death, Alfred Nobel’s friends described how, even at an advanced age, he could recite long sections from Byron’s Childe Harold. He may perhaps have chosen verse 178 from canto IV:

| There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, There is a rapture on the lonely shore, There is society, where none intrudes, By the deep Sea, and music in its roar: I love not Man the less, but Nature more, From these our interviews, in which I steal From all I may be, or have been before, To mingle with the Universe, and feel What I can ne’er express, yet cannot all conceal. |

Or perhaps, in moments of solitude, lines like these (II: 95-96):

| Thou too art gone, thou loved and lovely one! Whom youth and youth’s affection bound to me; Who did for me what none beside have done, […] Oh! ever loving, lovely, and beloved! How selfish Sorrow ponders on the past, And clings to thoughts now better far remov’d! But Time shall tear thy shadow from me last. All thou couldst have of mine, stern Death! thou hast: The parent, friend, and now the more than friend […] |

Or with self-irony and a humorous glint, this stanza from Don Juan (I:132):

| This is the patent age of new inventions For killing bodies, and for saving souls, All propagated with the best intentions ; Sir Humphrey Davy’s lantern, by which coals Are safely mined for in the mode he mentions, Timbuctoo travels, voyages to the Poles, Are ways to benefit mankind, as true, Perhaps, as shooting them at Waterloo. |

A Riddle (pdf)

Alas [– a fragment]

Gatchina [– a fragment]

Canto I (pdf)

Night-thoughts (pdf)

References

Manuscripts

Letter from Robert Nobel to Pauline Lenngren, 4th Dec. 1859, Nobelkapslarna, Svenska Akademiens arkiv (The Archives of the Swedish Academy).

Letter from Alfred Nobel to Olga de Fock, 8th[?] Oct. 1862, Alfred Nobels arkiv BII:2, Riksarkivet (The National Archives of Sweden).

Letter from C. Lesingham Smith to Alfred Nobel, 6th Oct. 1868, Alfred Nobels arkiv, Riksarkivet.

Letter from Mrs Isherwood to Alfred Nobel, 21th Jan. 1863, Alfred Nobels arkiv ÖII:6, Riksarkivet.

Letter from Alfred Nobel to Mrs Granny, undated typescript, Alfred Nobels arkiv BII:2, Riksarkivet.

Letter from Alfred Nobel to Bertha von Suttner, 13th March 1896, Alfred Nobels arkiv BI:10, Riksarkivet.

Letter from Mlle A. Lisogoub to Alfred Nobel, 8th May 1896, Alfred Nobels arkiv EII:4, Riksarkivet.

The poems of Alfred Nobel, A Riddle, Gatchina, Canto, Night thoughts, Alas, his “novel” Systrarne [The Sisters] and “filosofiska brev” [“philosophical letters”], Alfred Nobels arkiv BII:2, Riksarkivet.

Prints

Biederman, Edelgard, Chère Baronne et amie – Cher monsieur et ami. Der Briefwechel zwischen Alfred Nobel und Bertha von Suttner. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York , 2001.

Erlandsson, Åke, Alfred Nobels bibliotek. En bibliografi. Stockholm, 2002.

Fehrman, Carl, Du replis sur soi au cosmopolitisme. TUM/Michel de Maule, 2003.

Schück, Henrik & Sohlman, Ragnar, Alfred Nobel och hans släkt. Uppsala, 1926.

Sjöman, Vilgot, Vem älskar Alfred Nobel? Stockholm, 2001. Suttner, Bertha von, Memoiren. Stuttgart, 1909.

Internet

Erlandsson, Åke, Alfred Nobel’s Private Library, Björkborn, Nobelprize.org.

* Some deleted lines on Catherine’s sexual appetite for younger men:

The Hermitag – what mockery in that name!

The marble palace […]

Wrung from serfs wherewith an Empress paid

Her two-legged studs, they got a handsome price

All for a merit which we leave to guess!

The article was translated from Swedish to English by David Jones.

* Åke Erlandsson was born in 1938.

School of Education: Ph.Lic. in History of Literature, lecturer at the University of Umeå, Sweden, and at the University of Paris-Sorbonne (1971-73), School of Librarianship, chief librarian of the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy (1992-2001).

He has published inter alia: Litterära smakdomare (editor and co-author, 1987), Modern fransk prosa (1993), Alfred Nobels bibliotek: en bibliografi (2002). CD: Svensk Lyrik (co-editor and co-author, 1998). Internet: The Private Library of Alfred Nobel, Nobelprize.org.

First published 18 May 1998