English

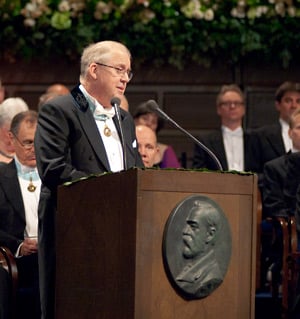

Speech by Dr Marcus Storch, Chairman of the Board of the Nobel Foundation, 10 December 2009.

|

| Dr Marcus Storch delivering the opening address during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall. Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009 Photo: Hans Mehlin |

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Honoured Laureates, Ladies and Gentlemen,

On behalf of the Nobel Foundation, I would like to welcome you to this year’s Nobel Prize Award Ceremony. I would especially like to welcome the Laureates and their families to this ceremony, whose purpose is to honour the Laureates and their contributions to science and literature.

Earlier today in Oslo the Peace Prize Laureate, President Barack Obama, was honoured “for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples”.

The Nobel Prizes that are being awarded today are part of a 108-year-old tradition, which by now encompasses 822 Laureates. From the very beginning, the Nobel Prize attracted great attention around the world as the very first international prize − by virtue of a cosmopolitan key statement in the will of Alfred Nobel: “It is my express wish that in awarding the prizes no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates, but that the most worthy shall receive the prize, whether he be Scandinavian or not.”

Thanks to the work of the prize-awarding institutions, the Prize has very much lived up to Nobel’s intentions. Today the Nobel Prize enjoys a unique standing. This can be illustrated in various ways. At the trivial level, a number of new prizes have been established with the ambition of becoming “a new Nobel Prize” in one field or another. Despite their obvious infringement on the Nobel name and reputation, this must be interpreted as a compliment to the Nobel Prize. After all, imitation is the highest form of flattery.

More important and interesting is that the Prize is also regarded as a measure of excellence. An index devised at Shanghai Jiao Tong University to rank the academic quality of universities around the world includes the number of Nobel Prizes that each respective institution of learning can show. When the European Commission, among others, wants to illustrate the relative competitiveness of the European Union in the scientific field compared to the United States, the number of Nobel Prizes is used as an indicator. Universities with Nobel Laureates advertise this fact in order to attract the best teachers and students, as well as interested donors.

Nevertheless, at regular intervals a perfectly legitimate question is asked: Can an institution like the Nobel Prize, with its roots in the late 19th century, keep up with today’s dynamic developments? When it comes to literature and efforts to promote peace, these are of course not affected in the same way by scientific and technological developments, as is the case with the science prizes. As we know, the volume, depth and intensity of development in the scientific field have increased in geometric progression since the age of Alfred Nobel.

The question of the current relevance of the Nobel Prize was recently asked in a well-publicised open letter in the magazine New Scientist. This letter expressed great appreciation for the role of the Nobel Prize in highlighting scientific excellence and making it better known to a broad general public. But, as the open letter quite correctly notes, Alfred Nobel could not have foreseen such issues as climate change or HIV/AIDS, the many advances achieved in new disciplines and the fact that this is often done within the framework of organisations, not by a single individual. The signatories thus felt that two new Nobel Prizes should be established, one in the field of global environment and health and a second in the life sciences with an emphasis on neuroscience, which they felt does not receive sufficient attention. Likewise, it should be possible to award the Prize to organisations, for example if the World Health Organisation (WHO) should succeed in eradicating malaria.

These opinions provided food for thought about the role of Nobel Prize work in relation to these important developmental trends.

A closer examination reveals that the Nobel Committees that perform this work have been fairly successful in reflecting the developments within their fields.

To begin with, Nobel Prizes have in fact been awarded in precisely the fields cited in the letter that Alfred Nobel could not have foreseen: concerning the threat of climate change through both the Chemistry and Peace Prizes, and with regard to HIV/AIDS in last year’s Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In neuroscience and genetics − fields where the signatories of the letter call for a new Prize − during the past 30 years 12 and 17 scientists, respectively, have been awarded a Nobel Prize.

Turning to the question of awarding the Prize to organisations or institutions, this possibility is included in the Statutes of the Nobel Foundation. To date, however, only the Norwegian Nobel Committee has taken advantage of this opportunity, and it has done so on a number of occasions over the past century. One very likely reason for this situation is that the prize-awarding institutions have actually read Nobel’s will carefully. Regarding the science prizes, in physics he speaks of a “discovery or invention”, in chemistry a “discovery or improvement” and in physiology or medicine a “discovery”. Eradicating malaria is not a discovery, but an application of discoveries. In literature and peace, however, he speaks of the person who has “produced … the most outstanding work” and “done the most or the best work”. The prize-awarding institutions apparently still share Nobel’s firm opinion that discoveries and inventions, as well as “outstanding” literary works, are made by creative individuals, not by institutions.

To summarise, a close look confirms the impression that the prize-awarding institutions have shown good flexibility within the framework of the Nobel disciplines in capturing important new trends. And the credit for this should go not only to the Nobel Committees in Sweden and Norway, since their prize work is based on a large-scale international network of colleagues who actively contribute their assessments of what is especially prize-worthy. This collaboration is what guarantees the international, cosmopolitan character of the Nobel Prize.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009