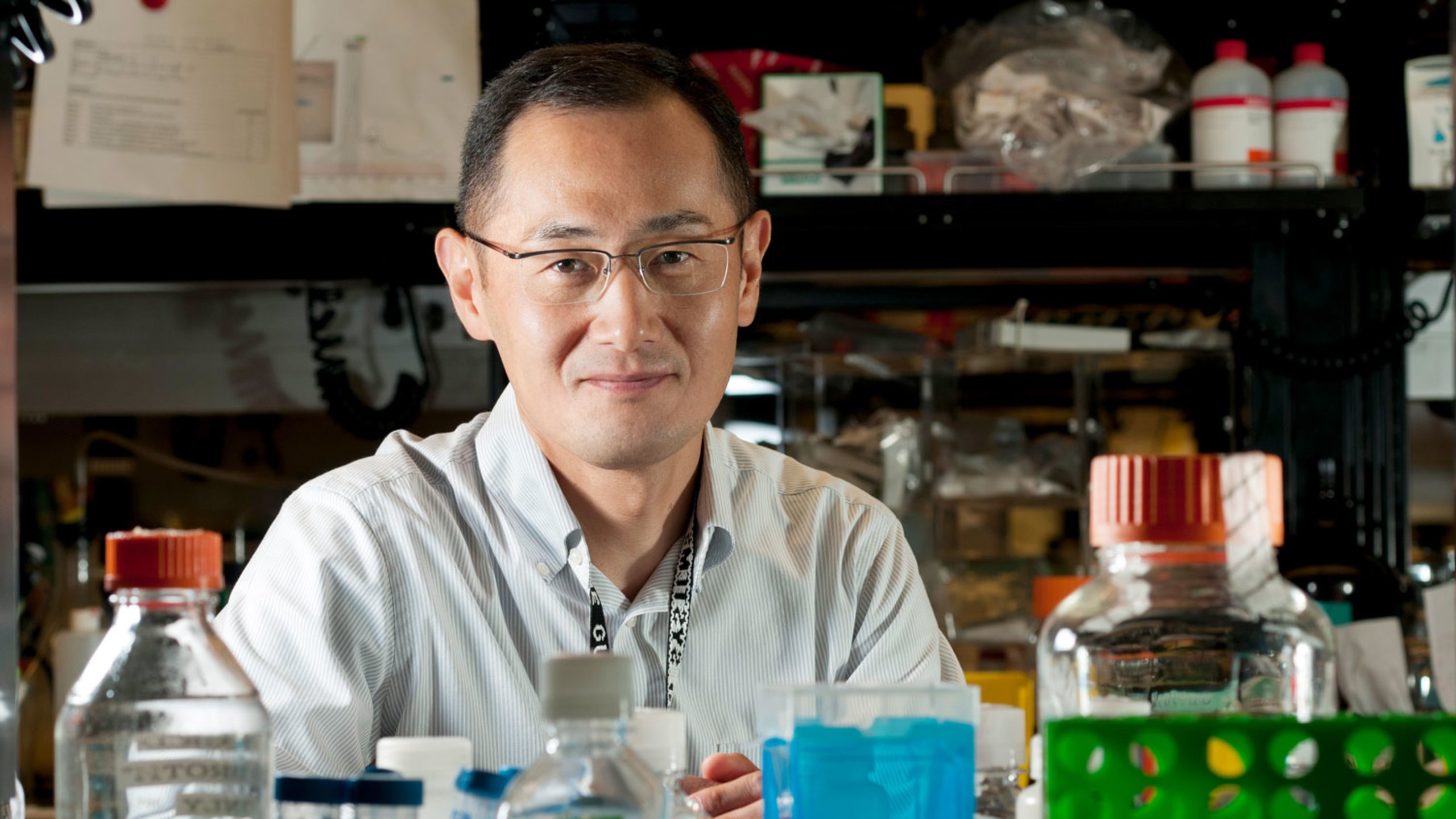

Shinya Yamanaka is a runner, a father and the man who first created stem cells from normal body cells. A pioneer of biomedical research, he describes how he was determined to find success in the face of all else.

Shinya Yamanaka began his career not as a scientist but as a surgeon, working at the Osaka National Hospital in Japan. It was a profession his father, Shozaburo, had encouraged him to pursue. Shozaburo, an engineer, had run his own business and was a great source of inspiration for the young Yamanaka. But when Yamanaka was 26 years old his father passed away from liver failure. Shozaburo had been suffering from Hepatitis C, which at the time had no known cause, or cure.

“His passing was very shocking to me. I felt powerless, useless. I became a doctor but I couldn’t help my own father,” says Yamanaka. “That was, I believe, one of the main reasons why I decided to change my career from surgeon to scientist.”

And so Yamanaka left his job as a surgeon and enrolled as a PhD student in the Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine. His vision: to help patients by developing cures for diseases as a scientist.

Shinya Yamanaka stands in front of a picture of his father, Shozaburo.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

Like many young researchers Yamanaka’s first forays into research were not straightforward. His first project involved conducting a simple experiment to determine how a blood platelet activating factor affected the blood pressure of dogs. Instead of seeing an increase in pressure, as he had expected, Yamanaka’s measurements showed the completely opposite result.

“I got super excited by that unexpected result. That’s the moment when I thought I should become a scientist rather than a physician because I enjoyed that moment very much. I reported [it] to my mentor and to my delight he got very excited too.”

Buoyed by enthusiasm, Yamanaka uncovered the underlying mechanism, which became the topic of his first research paper and PhD. His result had inadvertently presented him with a chance to discover something unique.

“As a scientist we don’t want to repeat what other people are doing, we want to be as unique as possible. But in reality thinking something very unique is getting more and more difficult,” he says. “Now I can see any failure as a chance. That result will teach you something else, something new.”

There are different routes to creating a unique piece of scientific research, adds Yamanaka. The first, like Einstein, is simply to be a genius. “But I cannot do that,” he laughs. The second is to stumble across an unexpected result, as he had just done.

There is also a third strategy, says Yamanaka: “Try to do something very important but very difficult.” In other words, take a risk. This was the approach that would lead to the Nobel Prize.

By 1999 Yamanaka was head of his own lab, at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST). His research interests had moved onto embryonic stem (ES) cells, in which he saw much promise for curing the diseases that he so wanted to defeat.

ES cells are fascinating to scientists as they have two very special properties – they are able to divide indefinitely and have the ability to become any type of specialised cell. Many researchers were spending their time investigating how to control this differentiation. How could they force them to become heart cells, or liver cells? Yamanaka, however, decided to take the opposite approach. Could he find a way to turn those specialised body cells back into stem cells?

“Many people thought it would be nice to reprogramme our skin cells back to [stem] cells,” he remembers. “The idea wasn’t very unique but most people didn’t take the risk because they thought it would take many years.”

Yamanaka had spent the years since his PhD in the US, as a post-doc at the Gladstone Institutes, where his interest in genetics was nurtured. But three years into his stay his family moved back to Japan so his daughter could start school. Spending time with his family had always been a welcome escape from any struggles he might be having in the lab. “Usually it’s just failure. Failure, failure, failure, success.”

Yamanaka missed his family terribly and after six months returned home himself. But relocating to Japan, initially to the Department of Oncology at Osaka City Medical School, was a culture shock. He suffered from depression and considered quitting science altogether.

But Yamanaka, a marathon runner, was used to the pain and frustration of trying to achieve his goal. “It’s hard to run a full marathon. Sometimes I don’t know why I am doing this, am I crazy?” he jokes. “But by completing that distance you can feel very good. And once you experience that kind of feeling you will do it again.”

Feeling he had nothing to lose, he was willing to take a risk.

Yamanaka had hypothesised that it may be possible to reprogramme body cells, also called somatic cells, by introducing factors that would switch on genes typically active in ES cells. He asked his student Kazutoshi Takahashi to work on the project – he was prepared for it to take decades to identify the correct number and combination of genes.

“I told him ‘Kazutoshi don’t worry. Most likely this won’t work but it’s ok. After ten years I’m going to have a small clinic. I have a medical licence and I’m going to hire you as a receptionist!’,” Yamakana says, laughing.

But to his surprise, Takahashi saw positive results on their initial combination of 24 factors. He still remembers the moment Takahashi came to tell him that their experiments had worked. “It was more like fear of discovery, not joy. The procedure was too simple, too easy.”

After narrowing the factors needed to just four, Yamanaka and Takahashi published their findings in the journal Cell in 2006, only six years after first beginning work. In 2007 they published a follow up demonstrating the technique in human cells, and also brought the number of factors down again, to three. Yamanaka called the embryonic-like stem cells induced pluripotent cells, or iPS cells.

Shinya Yamanaka takes a photo of the Nobel Prize guest book when collecting his 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Credit: Nobel Media

Ten years after his initial discovery, iPS cells have had a massive impact on biomedical research. As they are easily available and able to differentiate into virtually all types of cells they can be used to model and study diseases in the lab. Researchers can also use them to screen drugs, testing potential cures on types of human cell they were previously unable to source.

Yamanaka speaks of one boy, Ikkun, who suffers from a rare disease called fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in which muscles and soft tissue progressively turn into bone. “He often comes to our institute and whenever he is with us he asks us to take pictures. He wants us to develop an effective drug as early as possible, even one day earlier.”

“He knows most likely we cannot make it for him. But he wants us to do it for patients after him.” However trials with iPS cells indicate that a drug already on the market could help slow the disease. Clinical trials on human patients started in September 2017.

In theory iPS cells could also provide a way to grow new healthy organs in the lab – leading the way to a new era of regenerative medicine. An initial trial has already been carried out transplanting retinal cells derived from iPS cells into a patient suffering from macular degeneration.

Thanks to his work Yamanaka was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2012. Investigations are being carried out into diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, corneal disease, heart failure, spinal cord injury, cancer and arthritis – all of which have the potential to be treated with iPS cell technologies. However Yamanaka remains humble.

“I haven’t achieved my goal. I really want to help patients and we haven’t helped a single one. We need to continue working very hard and hopefully we can help many patients before I die.”

Shinya Yamanaka was speaking as part of the Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative in partnership with AstraZeneca.