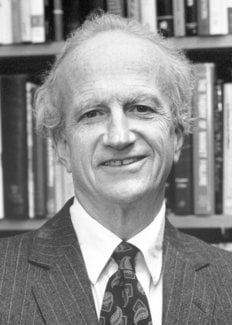

Gary Becker

Biographical

I was born in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, a little coal mining town in Eastern Pennsylvania, where my father owned a small business. He had first gone into business for himself after leaving Montreal and his family for the United States when he was only sixteen-years old. He moved many times in the eastern United States before settling in Pottsville in the mid-1920s. My two sisters, Wendy and Natalie, and brother, Marvin, were also born there. However, when I was four or five we moved to Brooklyn, New York, where my father became a partner in another business.

I went to elementary school and high school in Brooklyn. I was a good student, but until age sixteen was more interested in sports than intellectual activities. At that time I had to decide between being on the handball and math teams since they met during the same time period. It was indicative of my shift in priorities that I chose math, although I was better at handball.

My father had left school in Montreal after the 8th grade because he was eager to make money. My mother – whose family emigrated from Eastern Europe to New York City when she was six months old – also left after the 8th grade because girls were not expected to get much education. There were only a few books in our house, but my father kept up with the political and financial news, and my older sister read a lot. After my father lost most of his sight, I had the task of reading him stock quotations and other reports on financial developments. Perhaps that stimulated my interest in economics, although I was rather bored by it.

We had many lively discussions in the house about politics and justice. I believe this does help explain why by the time I finished high school, my interest in mathematics was beginning to compete with a desire to do something useful for society. These two interests came together during my freshman year at Princeton, when I accidentally took a course in economics, and was greatly attracted by the mathematical rigor of a subject that dealt with social organization. During the following summer I read several books on economics.

To be financially independent more quickly, I decided at the end of my first year to graduate in three years, a seldom used option at Princeton. I had to take a few extra courses during the next year, and I chose reading courses in modern algebra and differential equations for the summer afterwards. For the equations course, I was given a set of unpublished lectures that emphasized existence proofs and uniqueness of solutions to differential equations. I learned a lot about such proofs, but very little about actually solving one of these equations. Still, my heavy investment in mathematics at Princeton prepared me well for the increasing use of mathematics in economics.

I began to lose interest in economics during my senior (third) year because it did not seem to deal with important social problems. I contemplated transferring to sociology, but found that subject too difficult. Fortunately, I decided to go to the University of Chicago for graduate work in economics. My first encounter in 1951 with Milton Friedman‘s course on microeconomics renewed my excitement about economics. He emphasized that economic theory was not a game played by clever academicians, but was a powerful tool to analyze the real world. His course was filled with insights both into the structure of economic theory and its application to practical and significant questions. That course and subsequent contacts with Friedman had a profound effect on the direction taken by my research.

While Friedman was clearly the intellectual leader, Chicago had a first class group of economists who were doing innovative research. Especially important to me were Gregg Lewis’s use of economic theory to analyze labor markets, T.W. Schultz‘s pioneering research on human capital, Aaron Director’s applications of economics to anti-trust problems, and industrial organization more generally, and L.J. Savage’s research on subjective probability and the foundation of statistics.

I published two articles in 1952, based on my research at Princeton. But I realized shortly after arriving in Chicago that I had to begin to learn again what economics is all about. I published nothing else until an article written with Friedman and a book based on my Ph.D. dissertation came out in 1957. The book contains the first systematic effort to use economic theory to analyze the effects of prejudice on the earnings, employment and occupations of minorities. It started me down the path of applying economics to social issues, a path that I have continued to follow.

The book was very favorably reviewed in a few major journals, but for several years it had no visible impact on anything. Most economists did not think racial discrimination was economics, and sociologists and psychologists generally did not believe I was contributing to their fields. However, Friedman, Lewis, Schultz, and others at Chicago were confident I had written an important book. Support by the people I respected so highly was crucial to my willingness to persevere in the face of much hostility.

After my third year of graduate study I became an Assistant Professor at Chicago. I had a light teaching load and could concentrate mainly on research. However, I felt that I would become intellectually more independent if I left the nest and had to make it on my own. After three years in that position, I turned down a much larger salary from Chicago to take a similar appointment at Columbia combined with one at the National Bureau of Economic Research, then also located in Manhattan. I have always believed this was the correct decision, for I developed greater independence and self-confidence than seems likely if I remained at Chicago.

For twelve years I divided my time between teaching at Columbia and doing research at the Bureau. My book on human capital was the outgrowth of my first research project for the Bureau. During this period I also wrote frequently cited articles on the allocation of time, crime and punishment, and irrational behavior.

At Columbia I began a workshop on labor economics and related subjects–anything that interested us was “related.” This involved transplanting the workshop system of supervising doctoral research from Chicago – where it originated. After a few years, Jacob Mincer joined the Columbia department and became co-director of the workshop. We had a very exciting atmosphere and attracted most of the best students at Columbia. Both Mincer and I were doing research on human capital before this subject was adequately appreciated in the profession at large, and the students found it fascinating. We were also working on the allocation of time, and other subjects in the forefront of research.

I married for the first time in 1954, and have two daughters from that marriage, Judy and Catherine. To provide a better family atmosphere I lived in the suburbs and commuted to Columbia and the Bureau. Eventually, I began to tire of commuting and decided either to move into New York or to leave Columbia for another university. I also was beginning to feel intellectually stale.

My decision to leave was hastened by the student riots in 1968. I believed that Columbia should take a firm hand and uphold the right to free inquiry without student intimidation. The central administration wanted to do this, but it was incompetent, and was opposed by many faculty who behaved no better than the students.

In 1970, I returned to Chicago, and found the atmosphere there very stimulating. The department was still powerful, especially after it had added George Stigler and Harry Johnson. Stigler and I soon became close friends, and he had a very large effect on my subsequent intellectual development. We wrote two influential papers together: a controversial one on the stability of tastes, and an early treatment of the principle-agent problem. Stigler also renewed my interest in the economics of politics; I had published a short paper on this subject in 1958. In the 1980s I published two articles that developed a theoretical model of the role of special interest groups in the political process.

But mainly I worked on the family after returning to Chicago. I had much earlier used economic theory to try to understand birth rates and family size. I now began to consider the whole range of family issues: marriage, divorce, altruism toward other members, investments by parents in children, and long term changes in what families do. A series of articles in the 1970s culminated in 1981 in A Treatise on the Family . Since I continued to work on this subject, a greatly expanded edition was published in 1991. I have tried not only to understand the determinants of divorce, family size, and the like, but also the effects of changes in family composition and structure on inequality and economic growth. Most of my research on the family, and that by students and faculty at Chicago and elsewhere, was presented at the Workshop in Applications of Economics that Sherwin Rosen and I run.

For a long time my type of work was either ignored or strongly disliked by most of the leading economists. I was considered way out and perhaps not really an economist. But younger economists were more sympathetic. They may disagree with my analysis, but accept the kind of problems, studied as perfectly legitimate. During the past ten years I have received much tangible evidence of this shift in professional opinion, including the presidency of the American Economic Association, the Seidman Award, and the first social science Award of Merit from the National Institute of Health.

In 1983, the Sociology Department at Chicago offered me a joint appointment. I was happy to accept because this was an outstanding department. Its invitation to me gave a signal to the sociology profession that the rational choice approach was a respectable theoretical paradigm. James Coleman and I shortly thereafter began an interdisciplinary faculty seminar on rational choice in the social sciences that has been far more successful than we anticipated.

Until 1985, I had published only technical books and technical articles in professional journals. At that time, I was surprised by being asked to write a monthly column for Business Week magazine. Since I feared that I could not write for a general audience, I was inclined to turn the offer down. Finally, however, I agreed to do some columns on an experimental basis. It was a wise decision, for I was forced to learn how to write about economic and social issues without using technical jargon, and in about 800 words per column. Doing this has enormously improved my capacity to discuss important subjects briefly and in simple language. The pressure of having to do a column every month also makes me stay abreast of many subjects that interest the business and professional readers of the magazine.

I married for the second time in 1980 to Guity Nashat – my first wife died in 1970. This gave me two stepsons, Michael and Cyrus, to go with two daughters. Guity is the one who overcame my reluctance to do the Business Week columns. She is an historian of the Middle East with professional interests that overlap my own: on the role of women in economic and social life, and the causes of economic growth. The personal and professional compatibility she provides has made my life so much better.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Gary S. Becker died on 3 May 2014.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.