J. Robin Warren

Biographical

I was born on the 11th of June 1937, in North Adelaide, South Australia, the first child of middle-class parents. I am a fifth generation South Australian. South Australia is a charming state, a little overfull of the fact that, along with Victoria, it was settled by free settlers from England, who took part in a land investment program. There were no convicts. Elsewhere in Australia, the major cities began as prisons for Britain’s unwanted, when America became closed to them after the War of Independence. The original settlers arrived in 1836–7 and the beautiful city of Adelaide was chosen as the main settlement. It was imaginatively designed, with the main city square mile crossed by broad streets and surrounded by parkland. Adelaide rapidly expanded during the Victorian era, and by the end of the 19th century it was a bustling city of about 100,000 people.

I was born on the 11th of June 1937, in North Adelaide, South Australia, the first child of middle-class parents. I am a fifth generation South Australian. South Australia is a charming state, a little overfull of the fact that, along with Victoria, it was settled by free settlers from England, who took part in a land investment program. There were no convicts. Elsewhere in Australia, the major cities began as prisons for Britain’s unwanted, when America became closed to them after the War of Independence. The original settlers arrived in 1836–7 and the beautiful city of Adelaide was chosen as the main settlement. It was imaginatively designed, with the main city square mile crossed by broad streets and surrounded by parkland. Adelaide rapidly expanded during the Victorian era, and by the end of the 19th century it was a bustling city of about 100,000 people.

The Warrens migrated from Aberdeen in 1840. Their eldest son, my great grandfather John Campbell Warren, was a member of the local government, Captain of the Light Cavalry, and patriarch of a family of 16 children. He owned a large estate in the Adelaide Hills. At the turn of the century, he sent his sons to outback South Australia (Anna Creek) and Western Australia (Katanning) to open up huge areas for cattle and wheat. My father, Roger Warren, studied viticulture and became one of Australia’s leading winemakers.

My mother’s ancestors migrated from England to Adelaide with the first settlers in 1836–7. My grandfather, Sydney Verco, belonged to a dynasty of doctors. The Verco family still make up many of Adelaide’s doctors. He died young, leaving my grandmother, Alice, with no income and four children to feed and educate. Somehow with the help of the extended family, she managed to send all the children to private schools. She scratched and saved to get enough money to send her son, Luke, through medical school. My mother, Helen, had desperately wanted to be a doctor, but could not be similarly financially supported. She eventually trained as a nurse instead. I cannot remember my mother ever pressuring me to study medicine, but somehow this always seemed to be my aim. We were all very proud of my uncle Luke Verco, who was a captain in the Army Medical Corps during the Second World War. I still have clear memories of him in his uniform. After the war, he became a country general practitioner, and my favourite uncle.

My parents married during the depression. Life was not easy. When I was born, we lived at the seaside suburb of Brighton, which I only remember from photographs taken by my father. In 1939, we moved to my grandmother’s old home in the southern suburb of Unley. My earliest memories were of riding my little tricycle to a local private school, which would have roughly coincided with Japan’s entry into World War II. For me, the war was rather unreal. We knew it was something to do with the Japanese up north, who were bombing Northern Australia. I recall attending an exhibition of Japanese submarines caught in Sydney Harbour. There were books about our brave soldiers fighting Germans in North Africa. For children in quiet little Adelaide these were all faraway events, almost an adventure story.

Other things that we saw, without really understanding them, were the almost total absence of cars, and the impossibility of getting electrical goods for the home. One car on our street used a ‘gas producer’, which burnt coke and produced carbon monoxide to fuel the motor. We used to watch these cars, with rusty black burners attached to the back, in some wonderment. A car near our home had a gas bag on top of the roof, as big as the car itself, filled with coal gas. Petrol was almost unavailable, but this had little effect on me. Food and clothing were rationed, but my mother seemed to be able to keep the family well fed and clothed, even if our idea of luxury was ‘bread and dripping’, made with fat and meat juices from the roasting dish, smeared on bread. When the war ended, we were able to buy a refrigerator. Previously, food was kept cool in an ice chest.

During and after the war, I attended the local public primary school, Westbourne Park School. Education in those days was much more by rote than today, particularly learning how to spell columns of words and memorize multiplication tables. I suspect the balance now has tilted too far the other way. With the onset of calculators and then computers, arithmetic was no longer done in the head, although I never regret the ability. Rote learning was actually only a small part of our education – certainly not all of it, as the media often seems to suggest today. My children seemed to be expected to pick up spelling as they went along, reading and studying literature, but with the onset of increasing home entertainment they seem to read less than we did. We used to listen to the radio, and I made myself a crystal radio set, which enabled me to hear the radio in bed. My mother made sure that I could get any books I wanted, and I was an avid reader of all the usual boy’s adventure stories, both new and classic. I also used to read books about science.

As I grew older, I obtained my first bicycle, which I used to ride to school and visit my friends. In those days, the Adelaide suburbs were remarkably safe. You hardly needed to lock the house to go out (although mother always did). There seemed to be no worry about children being attacked. There were still very few cars on the roads, and the idea that it was unsafe for children to ride alone was a generation away. I also used to amuse myself riding in the Adelaide foothills, sometimes picking wild blackberries (which my mother made into beautiful jam) or catching occasional ‘yabbies’ (the local wild freshwater lobsters). I watched my father take family photographs with his old Voitlander camera, and I finally persuaded him to buy me a Kodak box camera for my 10th birthday. I soon obtained developing dishes and printing paper, and my lifelong hobby of photography was definitely started.

I was never good at sports at school, although I enjoyed a game of cricket (played at a pretty low level), but I did become more adventurous with my bicycle and camera, touring around the Adelaide Hills and taking landscape photographs. I was a bit of a loner, riding on my own and doing whatever I wanted, not having to worry about how fast or slow companions were. This did somewhat hinder my social skills, but no doubt made my eventual profession in pathology much easier.

As I entered my teenage years, I began my secondary education. This was at the oldest school in Adelaide, St Peter’s College, the same school Lord Florey attended. At least two previous generations of Warrens went there. I found my father’s name carved into a desk and dated 1917. Life there was quite different from the local primary school. It was much more competitive. The best students were in the top level, with four levels in each grade (year). They had an arrangement similar to English league football, with the bottom students in each term exams being relegated to the class below. This happened to me once, to my extreme annoyance, and I vowed to return to level one and stay there. Most students who later attended university were in the top class. The curriculum there included English literature, two foreign languages (usually Latin and French), mathematics (my favourite subject), physics and chemistry. All were required for matriculation to the science oriented university schools such as medicine or engineering.

Sport was an important part of the school curriculum. Unfortunately, I was never much good at it, and did not really enjoy it. However, I continued my weekend cycling and photography. I attended the school’s army cadet unit, where I learned army skills and, presumably, instant obedience. I particularly enjoyed the rifle shooting. Target shooting, which I learnt in the school cadets, became the primary sporting activity of my adult life.

I matriculated from the school in 1954, gaining a Commonwealth scholarship. These scholarships were the initial attempt by the Commonwealth government to provide free tertiary education for the masses. I still think it was an excellent idea. There were just about enough scholarships to cover anyone who wanted to enter the major University schools, such as medicine or engineering, so most people attending the University were provided with free education. The situation is much more complex now, with the government paying the fees, but requiring them to be repaid by the students when they start earning money.

Figure 1. A self portrait, drawn while I was working for my final exams in Adelaide, 1960.

About this time I had my first experience of girls. I only had brothers, and somehow my mother did not count. Girls had always been very distant and strange people, especially the snooty-looking ones who walked past our front gate on the way to the local catholic convent school. (I married a catholic girl from a different catholic school, who thoroughly agreed with my description above!) Just before matriculation, the students were expected to attend dancing classes and then invite girls to the annual school ball. At first this seemed a strange affair, trying to learn ballroom dancing with a lot of girls who seemed just as shy as me. However, we soon got the idea, and we began to have a lot of pleasure, with groups of boys and girls developing personal relationships. There was none of the ‘going steady’ culture, which seems to dominate that period in America, and certainly a generation later with my children. For us, it was all very easygoing and pleasant, nothing serious.

Also, during my matriculation year, an event occurred that was to mark most of my life. One morning, my mother found me unconscious on the back lawn. I recovered without apparent ill-effect, but some time later it recurred. I was soon diagnosed as suffering grand mal epilepsy. I was placed on phenobarbital, and then a variety of other drugs to try and control the seizures, but control remained imperfect. I was unable to obtain a driving licence, a major event for young people at that age. There were apparently numerous comments to my mother at the time from people, both professional, friends and relatives, who should have known better. Many apparently suggested keeping me at home, no university, definitely no medical school, and so on. Thank goodness, none of this filtered through to me at the time; it made life difficult and embarrassing enough as it was at that rather sensitive teenage period. Mother had enough sense to give me a free rein to do what I liked, and none of this was ever mentioned. It was only years later that I came to appreciate just how much my mother had gone through to support my independence and personal maturation. My cycling in the hills continued, never interrupted by epileptic attacks or by admonitions that it was ‘too dangerous.’ Apparently, mother was worried sick, but she never said a word about it.

I obtained entry to the medical school of the Adelaide University in 1955, and the next stage of my life began. The first year was a wonderful entry to the university environment. Much of the work was a repetition of the final year at school. There was far more freedom. For the first time, we learnt about responsibility; we could work or not, as we liked. The only difference was that at the end of the year, a pass or fail was on the student’s own shoulders. Help was always there, if we wanted it, but some of my colleagues revelled in the ability to do nothing. Luckily for me, I was enjoying the work too much to miss it. I particularly enjoyed botany and zoology, new subjects for me. I remember dissecting a frog and setting up its skeleton – my specimen showing a marked absence of any imagination, just bones glued to a piece of cardboard!

Both before and after starting university, I always read widely, including numerous scientific books and medical history books. Astronomy was a particular interest of mine at the time. I remember reading Fred Hoyle’s books about the universe. I read the Oxford Junior Encyclopaedia, all 12 volumes. I probably should have spent as much time reading textbooks! Unfortunately, while I found textbooks fascinating to read as my curiosity and interest dictated, when I had to learn them for exams, they tended to lose their charm.

Medicine began in earnest with the preclinical years two and three. I was at the medical school almost full-time. The medical school was set apart from the main university buildings and the direct association with the university during first year was largely lost. Most of our time was spent in the anatomy department dissecting a cadaver or learning bone and joint structure and attachments, then the inner organs and the brain. I have never regretted the chance to learn anatomy (and, in later years, pathology) in such detail, which today’s students do not have time for. While I do not remember all the anatomy, it soon comes back with a glance at Gray’s textbook.

We also learned physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, embryology and histology. I illustrated my notes for the latter two subjects with full colour sketches from the practical classes, using purple and pink pencils for haematoxylin and eosin. In those days there was only a very simple range of available drugs and, though we did not realise at the time, pharmacy and pharmacology were very simple in comparison to what the students need to know today.

The next adventure began with the clinical years four, five and six. In those days, the Royal Adelaide Hospital was the only general teaching hospital in South Australia. In both its scattered buildings and in its function, it was like a living museum. Some of the best wards were “temporary” buildings erected for World War I. One was named Verco Ward, after one of my mother’s uncles. Some of the more Victorian wards were like an old English moving picture; a huge barn-like structure, with beds along each wall and Sister at the high table at one end. Nobody argued with Sister, especially not the students, who were assigned patients to study and follow-up and were treated as the bottom of the social ladder (by everyone but the nurses – who wanted future doctors to marry – and the patients, who generally seemed to appreciate our attention). This three-year term of surgery, medicine and obstetrics and gynaecology, passed very quickly. There always seemed to be something new and interesting around the corner.

After medical school, life became very busy. We were called ‘Junior Resident Medical Officers’ – the equivalent of today’s interns. We actually were residents, living at the hospital residents’ quarters. A second government hospital opened, and I obtained a position there. At that stage in life, I was still very much an innocent, with very little it exposure to the outside world of finance and employment. All graduating medical students were given Junior Resident positions. These entailed about 100 to 120 hours per week working, with very little payment (I received £17–10 per week). Nevertheless, I was young and fit, and the constant work was actually very enjoyable. I bought a Leica M3 camera, and started to turn my hobby to professional subjects, photographing interesting clinical lesions. I do not think I have ever worked in a branch of medicine that I did not enjoy.

This period changed my life around again. The new hospital also provided a second obstetrics facility for the medical school. The obstetrics students lived in the resident’s quarters. Some of the students were young women. Their dormitory was near mine. We soon became good friends, and then I found myself very attached to one Winifred Williams. In fact, before we knew what had happened, I was spending all my spare time at her home. I remember one magic day, we wandered through the Botanic Gardens together, and it started to rain. Next thing we were arm in arm in the glasshouse, but we did not notice the flowers. Soon we were engaged and, a year later, married. For me, that was the biggest and best decision of my life, and so easy to do at the time.

I remained a little innocent about the big bad world outside. I did not realise how easy it was for us, with automatic positions provided – even if it was almost slave labour. Law students for instance, had to find clerking positions with private firms to complete their Articles of Clerkship, before they could practice at all. Other students had to find employment for themselves. I learned a valuable lesson at the end of my resident year. I assumed it was good manners to only apply for the second year position that I wanted, registrar in psychiatry. I did not get the post and found myself, to my surprise, unemployed. Luckily there were still a few positions available, and the one which appealed to me most was Registrar in Clinical Pathology at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, attached to the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

In practice, ‘Clinical Pathology’ meant mainly laboratory haematology, which I thoroughly enjoyed. We had a good deal of freedom and responsibility. Although the usual work entailed reporting on blood smears and bone marrow, we had a wide range of other tasks, including examining faeces for parasites, examining urine and testing skin and nails for fungus. I put my drawing skills to work again, with detailed sketches of the various ova, amoebae and other organisms we saw. It really was an excellent all-round position to give one an overall feeling for pathology.

By the end of that year, Win graduated MB BS, and we had our first baby on the way. My pay was just about double what I earned in the intern year and, in pathology, my time of work was largely during the day. Life was settling into an enjoyable routine, if less adventurous. I had learnt about employment by them, and I applied for every position advertised at the end of the year. My first choice was Temporary Lecturer in Pathology at the Adelaide University, and I obtained the position. The work there consisted largely of morbid anatomy and histopathology, under the guidance of Professor Jim Robertson, which completed my overview of pathology and convinced me to go for membership of the (then) new College of Pathologists of Australia. Our baby boy, John, was born and we thought he was so wonderful, we had to start another. Of course, the baby soon started to crawl around, still wonderful, but a constant handful. By the time we realised our mistake, it was too late and our second baby was on the way. Win was still trying to fit in her intern year (it took her four years in bits and pieces to finish).

Melbourne

Again I applied for every position possible, both in Australia and overseas. As it turned out, I was offered the position of Clinical Pathology Registrar at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. We moved to Melbourne, for one of the happiest periods of our lives. The pathology community in Melbourne was much bigger and more active than in Adelaide, and Sydney was only a short distance up the coast. Everything seemed to be at our fingertips. The work was similar to that at the Medical and Veterinary Institute two years before. A couple of years of clinical pathology under the tutelage of Dr David Cowling and Dr Bertha Ungar enabled me to pass the college exams in haematology and microbiology.

After this, I became Registrar in Pathology, for training in morbid anatomy and histopathology. All hospital deaths received a post-mortem examination, for which we were responsible each morning. After morning tea, we examined the day’s biopsy slides and presented them in a Grand Round, using a primitive old slide projector that was lit with two arcing rods of carbon. It really was quite an entertaining and educational show, with most of the surgeons present. Dr Doug Hicks, the head of department, would bark out questions to the resident and comments or answers to other questions. We had to work hard and fast, but Dr Hicks was an excellent teacher, and everybody learned from the show.

After four years in Melbourne, I finished my College membership and was a fully-fledged pathologist. Our second son, David, was born during our first year in Melbourne. Win somehow managed to fit in her intern year between babies. This was complicated by the unexpected arrival of twin sons, Patrick and Andrew, two years later. We had four sons under 31/2 years old! After this we decided that the Catholic Church methods of contraception needed assistance! Win was now able to practice, if only part time. This was very difficult, in an era when “women stayed home”. Part-time positions required a lot of talking, with promises to leave if she was not suitable (she was never asked to leave).

I was trying to obtain a position as pathologist at Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea, which was then in the process of obtaining independence from Australia. I thought I could obtain experience with some of the more exotic and unusual diseases. However, this had to be done through the Department of Foreign Affairs, and government red tape was extraordinarily slow. I was working in my room one afternoon, when a thickset man with a strong Germanic accent walked in and said, “You are working with me next year.” and walked out. There was no chance for explanation or argument. I discovered he was Professor Rolf ten Seldam, the Professor of Pathology at the University of Western Australia and the Royal Perth Hospital. He was apparently a man no one argued with, or at least not twice. So I gave the Department of Foreign Affairs one day to settle the position in Papua and when they failed to reply, I accepted the position in Perth, Western Australia.

Perth

We arrived in Perth in January 1968. In Melbourne, we had no trouble renting a flat for the family. In Perth, there was nothing to rent, especially with four children. We had little money and no experience of buying property. Luckily, our first real estate agent was a good choice. He found us a good house to buy and a rental property in the interim. What I had not realised was that he told the owners that I was ‘the new doctor at the Royal Perth’ – quite true, but the owner thought he meant the new medical superintendent, who had received a good deal of newspaper publicity, and not just the junior pathologist! Life quickly settled down.

Pathology at the Royal Perth Hospital was totally different from Melbourne. We went along at a much more leisurely pace, but with a much more flexible timetable. We did less work, but it seemed to take longer to do it. Perth was a small and isolated community. It has doubled in size over the last 30 years, with a population now of over one million. These days, most pathology training in Australia is in a single specialty. In Perth, this had always been the case, perhaps because of a lack of positions for training, other than haematology or morbid anatomy. Trainees were encouraged to keep the same position. In contrast, the eastern states, with most of Australia’s population in one quarter of the continent, provided numerous training positions in all branches of pathology. General training was considered to be the norm, to give a broad base in all branches of pathology, before specialising in one area, as I did. I think this helped me later when dealing with Helicobacter, but it made me something of an oddity to my colleagues in Perth, who had all specialised in their particular branch of pathology from the start, giving them an in-depth knowledge on a narrow base.

In 1970, our last child, Rebecca, was born, our first daughter. Since Win only had sisters and I only had brothers, our knowledge of the difference between boys and girls was strangely superficial. Somewhat to our surprise, with no pushing from us, our daughter was quite different from the boys. Where they enjoyed running around in the dirt and pulling things to pieces, she would sit inside playing with dolls. After this, Win managed to get more work, and became quite an experienced general practitioner. She decided to specialise in psychiatry, and was accepted into the college training scheme, which took most of her time into the early 1980s.

Helicobacter

During the 1970s, I wrote up a few interesting cases and developed an interest in the new gastric biopsies that were becoming frequent. I also attempted to develop improved bacterial stains for use with histological sections, as I describe more completely in my Nobel lecture. Then, in 1979, on my 42nd birthday, I noticed bacteria growing on the surface of a gastric biopsy. From then on, my spare time was largely centred on the study of these bacteria. Over the next two years, I collected numerous examples and showed that they were usually related to chronic gastritis, usually with the active change described by Richard Whitehead in 1972. I attempted, with some difficulty, to obtain a negative control series, by collecting cases reported as normal gastric biopsies. This was more difficult than I expected, because all gastric biopsies were coded the same, wherever they came from in the stomach. Almost all so-called normal biopsies were from the corpus. Normal biopsies from the gastric antrum were very rare, but I eventually found 20 examples, and none showed the bacteria. With this material available, I began to prepare a paper for publication.

In 1981, I met Barry Marshall, and we agreed to undertake a more complete clinico-pathological study. He could cover the clinical aspects and provide improved biopsies, specimens for culture, clinical history and endoscopy findings. This resulted in our papers of 1983 and 1984, linking the infection to duodenal ulcer and culturing a new organism. My letter to the Lancet in 1983 was a summary of the paper that I was preparing when I first met Barry Marshall. After this Barry and I continued our association, but he moved to the Fremantle Hospital. I was involved with the pathology related to several studies: Professor Goodwin, improving the accuracy of culture to diagnose the infection; Dr Ivor Surveyor, producing the breath test for diagnosis; and doctors Marshall and Morris, attempting to fulfil Koch’s postulates to demonstrate that the bacteria was a pathogen.

Winifred, who was much more literate than me, used to read our papers. She was able to point out clichés or excessive jargon, and suggest ways of making the work more widely readable. Before I met Barry, Win was the only person to accept my work and encourage me. Considering that much of this work was done after hours or at home, thereby stealing her husband, she had every right to be annoyed. Particularly as she was a doctor, and knew the standard teaching that nothing grows in the stomach, and therefore that I was trying to prove the ‘impossible.’ As a psychiatrist, she could have suggested I was mad. But she stood beside me and helped me when no one else would.

|

| Figure 2. Barry and I working in the pathology department, Royal Perth Hospital, 1984. |

My last major work was the pathology for a large study by Barry Marshall et al. to show the effect of eradicating the bacteria on the relapse rate of duodenal ulcer. The study extended over seven years. It clearly showed that, after successful treatment of the infection, recurrence of peptic ulcer was rare; otherwise, it was usual. For me, the study provided a wealth of material to study the associated pathology. It soon became clear that active gastritis was very closely related to the infection. Treatment of the infection produced a very rapid and complete resolution of the active changes in the surface epithelium. Other changes, including lymphoid infiltration of the stroma and some epithelial changes, disappeared more slowly or not at all. The active changes varied considerably. The classic severe changes described by Whitehead were present in about 10 to 20% of cases. At the other end of the spectrum, some biopsies showed only occasional single intraepithelial polymorphs. These epithelial changes were almost absolutely related to the infection. With experience, I found the same features in the mucosa from the corpus, usually much more mild, superficial and focal than the antrum. Finally, the duodenal ulcers seemed to be distal pyloric ulcers rather than true duodenal ulcers. They appeared to arise in the distal pyloric mucosa, or perhaps the gastroduodenal junction.

Figure 3. Working in my room at RPH, 1986.

By 1990, our findings began to be recognised by the medical community. We started to receive increasing numbers of honours and requests for attendances at meetings and lectures. It had been an interesting decade. After our initial publications in 1983–84, a wealth of further studies appeared, most of them apparently just repeating our work, with similar results. No one proved we were wrong. Yet in spite of this, no one but patients and local general practitioners appeared to believe our findings. Many patients demanded treatment, and some GPs were very keen to treat them. Otherwise, it seemed that only our wives stood beside us.

In 1996, I was invited to Japan for a lecture tour. The following year, a three-month tour of Germany and adjacent countries was arranged by Manfred Stolte and Hansjörg Meyer. This provided us with some real recognition for our work, and it seemed the fighting was over. The tour was a wonderful working holiday for Win and me. However, soon after our return, Win experienced difficulty eating, and investigation showed duodenal obstruction due to an inoperable pancreatic carcinoma. Win gradually deteriorated and died four months later. After spending this time caring for her, I decided the time had come to retire.

|

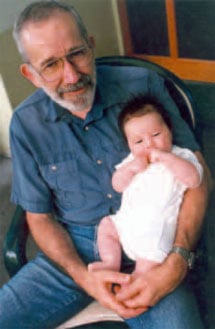

| Figure 4. The new generation – with my new granddaughter in 1997. |

At first, I spent most of my time trying to return to my hobby, photography. I intended to print my own pictures, using today’s improved digital technology. The early results were interesting, although more complicated than I had expected. Digital pictures only provide a narrow band of information. Only 256 tones are available for each colour. Outside this range is either total black or total white, with no information. This is quite unlike photographic film, which shows a flattening of the curve at each end of the tonal range, with an almost continuous variation still present in light and dark areas. I had to put this project aside to try and digitise all my old publications, microphotographs and other works, since I was receiving many requests for them. Now I have to put that aside, because the Nobel Prize has brought a stream of requests for my presence at meetings and presentations.

| Honours, Awards, Prizes for Medicine |

| Sixth International Workshop Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related organisms, 1991: Guest of honour. |

| Warren Alpert Foundation Prize 1994, Harvard Medical School, jointly with Dr. B. J. Marshall, “for research that has led to improved understanding and treatment of a specific disease: identifying Helicobacter pylori as a cause of peptic ulceration.” |

| Australian Medical Association – Western Australian Branch: 1995 Award. |

| Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia: Distinguished Fellows Award 1995, “for Distinguished Service to the Science and Practice of Pathology.” |

| The First Western Pacific Helicobacter Congress, February 1996: Inaugural Award, “In recognition of his contribution to the advancement of medical science through the co-discovery of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori.” |

| The medal of the University of Hiroshima, September 1996. |

| The University of Adelaide Alumni Association: Distinguished Alumni Award, 24 October 1996, “in recognition of your contribution to the healing of peptic ulcers, to the relief of human suffering and to huge world wide economic savings.” |

| The Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Award 1997, Paul Ehrlich Foundation, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, jointly with Dr. B. J. Marshall, “for your discovery of Helicobacter pylori as cause for peptic ulcer.” |

| Guest speaker at the Centenary Meeting of the German Society of Pathology, Berlin, May 1997. |

| Honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine, University of Western Australia September 1997. |

| Guest speaker at the World Helicobacter meeting, Lisbon 1997. |

| Faulding Florey medal, 1998, centenary of the birth of Lord Florey. |

| Australian Institute of Political Science, Cavalcade of Australian Scientists of the 20th Century, for “excellence in intellectual endeavour and contribution to international scientific research.” Presented at the Tall Poppy Dinner, Melbourne, May 18, 2000. |

| Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine for 2005, for “the discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.” |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Robin Warren died on 23 July 2024.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.