Award ceremony speech

| English |

General permission is granted for the publication in newspapers in any language. Publication in periodicals or books, or in digital or electronic forms, otherwise than in summary, requires the consent of the Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above underlined copyright notice must be applied.

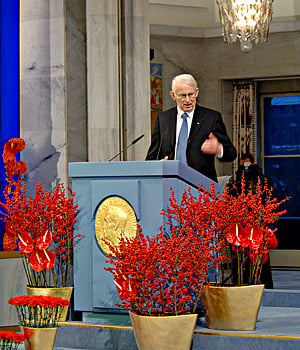

Presentation Speech by Professor Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Oslo, 10 December 2008.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2008

Photo: Ken Opprann

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highness, Laureates, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The Norwegian Nobel Committee’s announcement on the 10th of October of this year’s Peace Prize award began as follows: “The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2008 to Martti Ahtisaari for his important efforts, on several continents and over more than three decades, to resolve international conflicts. These efforts have contributed to a more peaceful world and to ‘fraternity between nations’ in Alfred Nobel’s spirit.”

We congratulate Martti Ahtisaari on this year’s Peace Prize! Paljon onnea, Martti Ahtisaari!

The 10th of December is the most important date in the Nobel year. On that day the prizes for medicine, physics, chemistry and literature are awarded in Stockholm. The economics prize in memory of Alfred Nobel is also awarded there. We salute each and every one of the Laureates who will be receiving their awards in Stockholm a little later today. And the Peace Prize, as you see, is awarded in Oslo. Nobel laid down in his will that it should be awarded by a committee “of five persons to be elected by the Norwegian Storting”. Here we are, up on the stage, together with the Committee’s Secretary.

Nobel also decided that all the prizes should be awarded on the basis of achievements “during the preceding year”. On that point I think all the committees must simply admit their failings. The Norwegian Nobel Committee, at any rate, has to declare that there was nothing so very special about 2008 that it could have led to the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Ahtisaari today. For it is being awarded to him precisely for “his important efforts, on several continents and over more than three decades”. It is not easy to take every sentence in Nobel’s will absolutely literally.

In Norway we feel that we know Ahtisaari well. Many Norwegians have met him; many of them are here today. He has had a long career as both a Finnish and an international politician. What is more, he has Norwegian roots! His great-grandfather was from Tistedalen in the county of Østfold. I see that Ahtisaari himself wondered in an interview whether it might be held against him that he was allegedly “12.5 per cent Norwegian”. It may well be that we have treated Norwegian candidates especially restrictively in recent decades. In 1921 and 1922, however, the Norwegian Nobel Committee was bold enough, awarding the Prize first to Christian Lange and in the following year to Fridtjof Nansen. So two Norwegians have received the Peace Prize, as against five Swedes and one Dane. Not until today has the Prize gone to a Finn. But in that connection we have listened to Alfred Nobel. He urged that the worthiest candidate should receive the Prize “whether he be Scandinavian or not”.

Martti Ahtisaari was born in Viborg, but during the Winter War he moved with his mother to Kuopio and later to Uleåborg. His father was at the front. His experience in Viborg, then Finland’s second largest city, which was incorporated into the Soviet Union after the war, and from which almost the entire Finnish population moved, “explains my desire to advance peace and thus help others who have gone through similar experiences as I did”. As early as in 1960, when he was only 23, Ahtisaari went to Karachi in Pakistan, where for three years he was in charge of building up a YMCA centre for physical education and teacher training. This accustomed him to living in an international environment. In 1965, after studying at the Helsinki University of Technology, Ahtisaari was recruited to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. His special interest there was development aid.

Ahtisaari was to have nearly the whole world as his field of activity. In 1973 he became Finnish Ambassador to Tanzania. In 1977 he was appointed United Nations Commissioner for Namibia as well as the Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Namibia. Namibia was to be for fourteen years the country to which he devoted his greatest efforts, although in the same period he also undertook several different international and Finnish assignments.

Of his many achievements as a peace negotiator, Ahtisaari rates his work in Namibia highest. The mediation took such a long time. There were so many players and dimensions involved. The United States and the Soviet Union engaged themselves. The Cold War made itself very much felt also in southern Africa. In the neighbouring country Angola a civil war was fought in which both Cuba and South Africa participated. Namibia was formally under UN supervision, but was in fact ruled by South Africa. The independence movement SWAPO grew steadily stronger.

The peace process was stimulated by the end of the Cold War. It also moved forward thanks to the emergence of a new white South Africa under F.W. de Klerk. But at the very centre of all this, holding all the threads in his hand, stood Martti Ahtisaari. He has been called “Namibia’s midwife”. A midwife sometimes stands between life and death. No single diplomat did more than he did to deliver Namibia’s independence, on the 21st of March 1990, after 24 years’ struggle. Today Ahtisaari is an honorary citizen of the country. Many boys in Namibia have been named after Martti. That must be at least as great an honour as being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

We thank Ahtisaari for his work in Namibia!

In Namibia, Ahtisaari had a mandate from the United Nations. For many years, he was obliged to relate to many different parties at many different levels. The situation in Aceh was completely different. There was a grave dispute over the status of Aceh between the central government authorities in Djakarta on the one hand and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) on the other. GAM had been seeking independence since 1976. There had been bloody battles. As it always does, the civilian population suffered most from the conflict. At least 15,000 people lost their lives. One village became known as the “Widows’ town”. Its men had either been killed or disappeared up into the mountains. In 2003 a peace accord concluded the previous year had broken down. Everything appeared to be back where it started. The parties had not spoken to one another for 20 months.

In that situation, with his organization Crisis Management Initiative (CMI), Ahtisaari launched an initiative. They had no international mandate. They saw opportunities where others only saw conflict. But they did think the work would take time. As Ahtisaari said, “When a married couple have not spoken to each other for 20 months, you can’t expect love to bloom immediately”. Love may not have bloomed, but the negotiations made rapid progress. In January 2005, Ahtisaari and CMI brought the parties together in Finland. Seven months later, the government and GAM signed a peace treaty in Helsinki.

A natural disaster contributed to the solution. The indescribable tsunami had hit Aceh particularly hard. At least 170,000 people died there. For all its horror, the disaster prepared the ground for peace. But natural catastrophes do not necessarily pave the way to peace. We saw that in Sri Lanka, where developments took a wrong turning despite the tsunami. Someone had to bring the parties together. Someone had to provide a suitable context. Ahtisaari and CMI managed to get the parties to agree that Aceh was to be part of Indonesia, but with extensive autonomy. GAM would hand in their weapons and be transformed into a political party. The process has gone surprisingly well, although challenges remain. An election is to be held in April 2009. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono of Indonesia has called Ahtisaari “the master of peace”.

We thank Ahtisaari for the solution in Aceh!

The Balkans are the third region in which Ahtisaari’s mediation has produced significant results. In Bosnia-Hercegovina he worked as a mediator for the United Nations. In 1999 he contributed, together with Russia’s Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, to bringing the war over Kosovo to an end. It was the two of them between them who got Slobodan Milosevic to stop the war. Ahtisaari is not one to boast about his achievements. Concerning Kosovo, he has said in an interview that Chernomyrdin and he “did not negotiate with Milosevic. We simply presented an offer which would make it easier to put a stop to the bombing, provided he committed the Yugoslav government to certain principles”.

No one can solve every international problem. Sometimes the parties are too far apart. In such cases, we have to be satisfied if the matter is brought just a few steps closer to a solution. For the past few years, Ahtisaari has striven hard to find a lasting solution for Kosovo. In November 2005 he was appointed Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General for the future status of Kosovo. This was a difficult task. The parties were very far apart, divided by centuries of bitter history. The last twenty years had seen a more or less continuous crisis. Serbia was fundamentally opposed to independence for Kosovo. There was nothing the Kosovo Albanians, eventually accounting for over 90 per cent of the population, for their part wanted more. In Aceh, a compromise was found. In Kosovo, no compromise was possible. In January 2007, Ahtisaari put forward his proposal for a solution. Kosovo would become virtually independent, subject only to some international supervision. The Serbs in Kosovo would be granted considerable autonomy, and have the right to maintain certain ties with Serbia. The proposal met with massive opposition in Serbia. The Kosovo Albanians were just as strongly in favour.

Ahtisaari’s proposed solution was never adopted by the UN Security Council. Russia, with her close links to Serbia, was against it. In July 2007, Ahtisaari declared his mission over. Further negotiations, inspired by the USA, the EU and Russia, failed to produce a solution that both parties could accept. So on the 17th of February 2008, the Kosovo Albanians declared Kosovo independent. The new state was quickly recognised by the USA and most EU countries, and today over fifty countries have taken the same step. On the 10th of October Ahtisaari heard that Macedonia and Montenegro had recognised Kosovo. Then he got the phone call about the Nobel Peace Prize. It must have been a good day!

Serbia, with Russia’s support, still objects to the new state. It can nevertheless be said that Ahtisaari’s solution for Kosovo has to a large extent been put into practice. Kosovo has become independent. The conflict had no other solution. There are, however, many signs that the Serbian minority will be more or less integrated with Serbia, contrary to Ahtisaari’s plan.

We thank Ahtisaari for his work to solve the Kosovo conflict.

The scale and scope of Ahtisaari’s activities are almost beyond belief. His greatest achievements have been mentioned. They are linked to Namibia, Aceh, and Kosovo. But he has also made important contributions to peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland, in Central Asia, and on the Horn of Africa. In addition to all this, he has managed to serve for six years as Finland’s President. During his term, from 1994 to 2000, Finland’s economy underwent significant improvement. Finland joined the European Union. Boris Yeltsin and Bill Clinton met in Helsinki. But with the Finnish political establishment in attendance here in the Oslo City Hall, we must take care not to give Ahtisaari too much of the credit for these developments.

In 2008, Ahtisaari and Crisis Management Initiative have been involved in negotiations concerning peace in Iraq. In April, in Helsinki, in cooperation with several American institutions, and with Ahtisaari as “senior adviser”, CMI induced 36 Iraqi politicians to agree on a declaration in principle on peace in Iraq. The declaration stated that dialogue and negotiations must be the most important keys to solving the country’s problems. “Facilitators”, as they are called, from Northern Ireland and South Africa are also engaged in this work. CMI and Ahtisaari are continuing to lend a hand in the ongoing process.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has often awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to the parties in a conflict. It is the parties, and their representatives, who take the personal and political risk of entering into peace agreements. But mediators, too, face major challenges. And the parties in a conflict nearly always need help in reaching their objectives.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has honoured mediators from Theodore Roosevelt in 1906 to Kofi Annan in 2001 and Jimmy Carter in 2002. Ahtisaari is in other words one of an exclusive group of peace negotiators who have made decisive contributions to peace and reconciliation in the world. His efforts have been untiring, and he has achieved good results. Ahtisaari has shown what parts mediators of many different kinds can play in the resolution of even the most difficult international conflicts.

Mediators no doubt differ as widely as most people. Ahtisaari has for his part said, “I have learned that you do not achieve peace just by saying nice things to the parties. You have to be sincere. You have to have the courage to tell people that they are acting counter-productively. I am sincere. I am not always amiable.” This may not sound too difficult. In Aceh, he asked the parties head on: “Do you want to win the war, or do you want peace?” Optimism is important in mediation efforts. Ahtisaari believes every conflict can be resolved. Every: that’s optimism for you. Having Finnish “sisu” must have been a great help. So must the support of his wife, Eeva. The ability to listen, and to go straight to the core of problems, is decisive. It has often been said, moreover, that you achieve most if you are not too busy winning credit for yourself. That need not prevent one from afterwards receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

Only very few of us can become peace mediators at a high international level. But we can all be peace mediators at a national or local level, in the neighbourhood, at schools, or in families. In this respect universities and schools can make valuable contributions. Ahtisaari has put it as follows: “We must all look in the mirror and ask ourselves have I done my best for peace.”

I usually wind up my Nobel addresses with literary quotations. This year the writer has to be Finnish. The words were written in 1926 by Frans Eemil Sillanpää. In 1939 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the only Finn to have won it. The translation from Finnish to Norwegian is by Jan Erik Kaplon, and from Norwegian to English by Peter Bilton. I read it as a greeting from Finland’s only Literature Laureate to the country’s first Peace Prize Laureate:

“At bottom, all humanity shares a common fate. Our distress is common.

We must therefore honour the efforts every human being makes to alleviate and remove our common distress.

Every war is a disgrace to those who wage it, and to the whole of mankind. War always ends in misery. Man only does his good deeds in times of peace. Only then are we able to prevent distress. Whoever builds peace, builds humanity.” “Se joka rakentaa rauhaa, rakentaa ihmisyyttä.”

We congratulate Martti Ahtisaari on the Nobel Peace Prize. Parhaat onnittelut, Martti Ahtisaari! The Norwegian Nobel Committee hopes that others will be inspired by your efforts and your results.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.