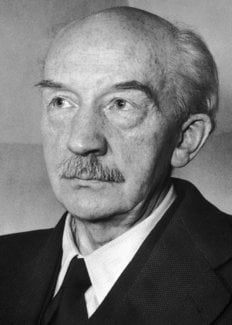

Walther Bothe

Biographical

Walther Bothe was born on January 8, 1891, at Oranienburg, near Berlin.

From 1908 until 1912 he studied physics at the University of Berlin, where he was a pupil of Max Planck, obtaining his doctorate just before the outbreak of the 1914-1918 war. From 1913 until 1930 he worked at the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt in the same city, becoming a Professor Extraordinary in the University there. In 1930 he was appointed Professor of Physics, and Director of the Institute of Physics at the University of Giessen.

In 1932 he was appointed Director of the Institute of Physics at the University of Heidelberg, in succession to Philipp Lenard, becoming in 1934 Director of the Institute of Physics at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research (re-established in 1948 as Institute of Physics at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research) in that city. At the end of the Second World War, when this Institute was taken over for other purposes, Bothe returned to the Department of Physics in the University, where he taught until the illness which had handicapped him for several years compelled him to restrict the scope of his work. He was able, however, to supervise the work of the Institute of Physics in the Max Planck Institute and he continued to do this until his death in Heidelberg on February 8, 1957.

Bothe’s scientific work coincided with the opening up of the vast field of nuclear physics and the results he obtained led to new outlooks and methods.

He was, during the First World War, taken prisoner by the Russians and spent a year in captivity in Siberia. This year he devoted to mathematical studies and to learning the Russian language; in 1920 he was sent back to Germany.

He then collaborated with H. Geiger at the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt in Berlin. Together with Geiger, whose influence determined much of his scientific work, he published, in 1924, his method of coincidence, by which important discoveries were subsequently made. It is based on the fact that, when a single particle passes through two or more Geiger counters, the pulses from each counter are practically coincident in time. The pulse from each counter is then sent to a coincidence circuit which indicates pulses that are coincident in time. Arrays of Geiger counters in coincidence select particles moving in a given direction and the method can be used, for example, to measure the angular distribution of cosmic rays. Bothe applied this method to the study of the Compton effect and to other problems of physics. Together he and Geiger clarified ideas about the small angle scattering of light rays and Bothe summarized their work on this problem in his Handbuch article published in 1926 and 1933, establishing the foundations of modern methods for the analysis of scatter processes. From 1923 until 1926 Bothe concentrated, especially on experimental and theoretical work on the corpuscular theory of light. He had, some months before the discovery of the Compton effect, observed, in a Wilson chamber filled with hydrogen, the short track of the recoil electrons of X-rays and he did further work on the direction of the emission of photo electrons. Together he and Geiger related the Compton effect to the theory of Bohr, Kramers, and Slater, and the results of their work provided strong support for the corpuscular theory of light.

In 1927 Bothe further clarified, by means of his coincidence method, ideas about light quanta in a paper on light quanta and interference.

In the same year he began to study the transformation of light elements by bombardment with alpha rays. The resulting fission products had, until then, been seen by the eye only as scintillations, but Bothe, in collaboration with Fränz, made it possible to count them by means of their needle counter.

In 1929, in collaboration with W. Kolhörster, Bothe introduced a new method for the study of cosmic and ultraviolet rays by passing them through suitably arranged Geiger counters, and by this method demonstrated the presence of penetrating charged particles in the rays, and defined the paths of individual rays.

For his discovery of the method of coincidence and the discoveries subsequently made by it, which laid the foundations of nuclear spectroscopy, Bothe was awarded, jointly with Max Born, the Nobel Prize for Physics for 1954.

In 1930 Bothe, in collaboration with H. Becker, bombarded beryllium of mass 9 (and also boron and lithium) with alpha rays derived from polonium, and obtained a new form of radiation that was even more penetrating than the hardest gamma rays derived from radium, and this led to the discovery of the neutron, made by Sir James Chadwick in 1932.

At Heidelberg, Bothe was able, after much difficulty, to obtain the money necessary for building a cyclotron. He worked, during the 1939-1945 war, on the diffusion theory of neutrons and on measurements related to these.

In June 1940 he published his Atlas of Cloud-Chamber Figures.

He was a member of the Academies of Sciences of Heidelberg and Göttingen, and a Corresponding Member of the Saxon Academy of Sciences, Leipzig. He was awarded the Max Planck Medal and the Grand Cross of the Order for Federal Services. In 1952, he was made a Knight of the Order of Merit for Science and the Arts.

Bothe’s remarkable gifts were not restricted to physics. He had an astonishing gift of concentration and his habit of carefully making the best use of his time enabled him to work at great speed. In the laboratory he was often a difficult and strict master, at his best in discussions in small classes there, but in the evenings at home he was, with his Russian wife, very hospitable and all the difficulties of the day were then forgotten.

To his hobbies and recreations he gave the same concentration and intensity of effort that he gave to his scientific work. Chief among them were music and painting. He went to many musical concerts and himself played the piano, being especially fond of Bach and Beethoven. During his holidays he visited the mountains and did many paintings in oil and water colour. In these his style was his own. He admired the French impressionists and was eager and vigorous in his discussions of the merits and demerits of various artists.

Bothe married Barbara Below of Moscow. Her death preceded his by some years. They had two children.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Walther Bothe died on February 8, 1957.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.