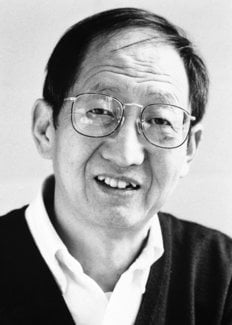

Daniel C. Tsui

Biographical

I tend to partition my life into three compartments: childhood years in a remote village in the province of Henan in central China, schooling years in Hong Kong, and the years since I came to attend college in the United States. The only thread connecting them is the kindness, generosity and friendship from the people around me that I have experienced all my life.

My childhood memories are filled with the years of drought, flood and war which were constantly on the consciousness of the inhabitants of my over-populated village, but also with my parents’ self-sacrificing love and the happy moments they created for me. Like most other villagers, my parents never had the opportunity to learn how to read and write. They suffered from their illiteracy and their suffering made them determined not to have their children follow the same path at any and whatever cost to them. In early 1951, my parents seized the first and perhaps the only opportunity to have me leave them and their village to pursue education in so far away a place that neither they nor I knew how far it truly was.

In Hong Kong, I began my formal schooling at the sixth grade level with fear and trembling, mixed with some pride and elation. I remember the difficulties that I encountered in not knowing the Cantonese dialect in the beginning, but, even more vividly, the overwhelming kindness of schoolmates who went out of their way to help by offering me their friendship, bringing me into their circle, and taking me to their out-of-class activities. In the middle of my second year in Hong Kong, I entered Pui Ching Middle School, which was known for being outstanding, especially in natural science subjects. Many of the teachers there were overqualified. They were the brightest graduates of the best universities in China and under normal circumstances would have been highly accomplished scholars and scientists. The upheaval of war in China, however, forced them to hibernate in Hong Kong teaching high school kids. They might not have been the best teachers pedagogically, but their intellects and their visions inspired us. Even their casual remarks and the stories from their romantic reminiscences of the glorious days at Peking University could leave indelible marks on us. It was they, I think, who in their unconscious ways dared us students, living in a most commercialized city, to look beyond the dollar sign and see the exploration of new frontiers in human knowledge as an intellectually rewarding and challenging pursuit.

I graduated from Pui Ching in 1957 and was admitted to the medical school of National Taiwan University in Taiwan. However, since it was unclear at the time how my parents were and whether I could return to them in China, I stayed in Hong Kong and entered a two-year special program run by the government to prepare Chinese high school graduates for the University of Hong Kong. In late spring the next year, I received the surprising good news from the United States that I was admitted with a full scholarship to my church pastor’s Lutheran alma mater, Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. I arrived on campus right after Labor Day 1958, and there spent the best three years of my life. It was there that I had for the first time the leisure to wrestle with my Lutheran faith and to think through and make some sense out of my life experience. In Hong Kong, I was always extremely busy as a scholarship student, heavily involved with church activities and responsibilities, and worn-out from long distance daily commuting. Here, I was free to read, to learn and to think through things at my own pace. I knew from the start that I would go to graduate school, and the choice of subject and school was never a problem. C.N. Yang and T.D. Lee were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1957 and they both went to the University of Chicago. Yang and Lee were the role models for Chinese students of my generation and going to the University of Chicago for a graduate education was the ideal pilgrimage.

The University of Chicago was intense and intellectual. I liked its being in a major city, its cosmopolitan atmosphere, and even its grimy buildings and the austerity they appeared to convey. There, I luckily met and fell in love with Linda Varland, an undergraduate in the college, and we were married after her graduation. I was also fortunate that Royal Stark, who had just joined the physics faculty as a solid state experimentalist, took me on as a research assistant in the building-up of his laboratory. I realized quite early that I wanted to do experimental physics and that I lacked the aptitude for colossal experimental setups and also the taste for grandeur. I wanted to do tabletop experiments and be allowed to tinker. Royal Stark trusted me and let me try my hands on everything in his laboratory. I was given the best opportunity to learn from the bottom up: from engineer drawing, soldering, machining, and design, to construction and building of our laboratory apparatus. By the time I received my Ph.D., I was confident that I could make a living using the technical skills I had learned there. Since I could always fall back on a job using my technical skills, I reasoned, why not then take a risk and try a research position doing something entirely novel and at the same time intellectually challenging.

I left Chicago in early spring 1968 and took a position in Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey to do research in solid state physics. I found myself a niche in semiconductor research, though I never got into the main stream either in semiconductor physics, which was mostly optics and high energy band-structures, or its use in device applications. I wandered into a new frontier, which was dubbed the physics of two-dimensional electrons. In February 1982, shortly after the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect, I moved to Princeton and started teaching.

Many of my friends and esteemed colleagues had asked me: “Why did you choose to leave Bell Laboratories and go to Princeton University?”. Even today, I do not know the answer. Was it to do with the schooling I missed in my childhood? Maybe. Perhaps it was the Confucius in me, the faint voice I often heard when I was alone, that the only meaningful life is a life of learning. What better way is there to learn than through teaching!

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.