by Ivar Libæk*

The International Committee of the Red Cross was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917, 1944 and 1963 – on the third occasion jointly with the League of Red Cross Societies. This makes the Red Cross unique: no recipient has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize as often as this organisation. The very first time the peace prize was awarded, in 1901, the Norwegian Nobel Committee chose to pay tribute to the founder of the Red Cross, Henry Dunant from Switzerland. Thus his story is a natural point of departure when examining the role of the Red Cross in the history of the peace prize.

It all began in Solferino

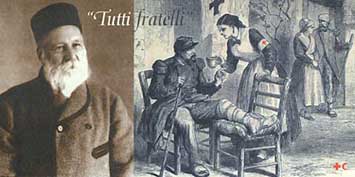

On 24 June 1859, two armies stood poised to fight outside the village of Solferino in Northern Italy. Emperor Napoleon III of France was backing Sardinia against Austria-Hungary during the second War of Italian Independence. When the Battle of Solferino was over, more than 30,000 soldiers had lost their lives, and thousands more had been wounded and maimed. A young Swiss businessman named Henry Dunant happened to witness the battle, and the sufferings and lack of medical treatment he observed, made a profound and lasting impression on him. He swiftly mobilised the local people into action, setting up crude infirmaries in churches, monasteries and makeshift tents. All the wounded soldiers, regardless of which side they were fighting on, were given care. “Tutti fratelli” – they are all our brothers, said the women who helped Dunant at Solferino. The germ had been sown.

Postcard in memory of Henry Dunant and the Battle of Solferino (1859). The inhabitants of Castiglione delle Stiviere helped Dunant in caring for wounded soldiers of different nationalities after the bloody battle.

The founding of the Red Cross and the Geneva convention

After Solferino, Dunant returned to Switzerland. His experiences from witnessing the battle and the relief efforts he had organised inspired him to write A Memory of Solferino (1862), where he launched his plan: in times of peace, all nations should establish voluntary relief societies to aid sick and wounded soldiers during times of war. The objective was that all soldiers – whether friend or foe – should receive medical care. The book was printed at Dunant’s expense, and with a preface written by the Swiss general Guillaume-Henri Dufour it was spread to national leaders and influential politicians throughout Europe.

Dunant’s book was translated into a number of languages, and his simple yet realistic idea had great appeal. In the autumn of 1862 he was approached by Gustave Moynier, a lawyer who was president of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare. On their initiative a committee was formed in February the following year, with Dunant, Moynier, General Dufour and two physicians as its members. Thanks to the committee’s efforts and Dunant’s skills of persuasion, an international conference was held in Geneva in the autumn of 1863 with delegates from 17 countries. At the end of this conference, on 29 October 1863, the International Committee for the Relief of the Wounded was founded (now the International Committee of the Red Cross), composed of the five Swiss members that had convened in February. A red cross on a field of white was adopted as the emblem of the organisation, and national Red Cross societies were to be set up in each of the countries represented at the conference.

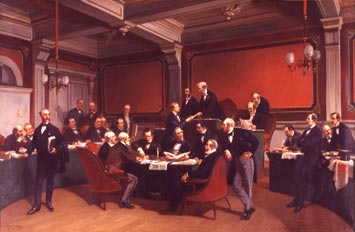

The newly established committee wasted no time. Delegates from a number of countries convened in 1864 to adopt the first Geneva Convention. Under this convention, all medical installations in the field in time of war are to be granted immunity as long as they provide shelter for the wounded, and medical personnel are to treat all wounded persons impartially, under the protection of badges and flags displaying the Red Cross emblem. In the course of the following two years, twenty states had ratified the convention. Dunant’s idea had taken hold.

Signing of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864 (painting by Armand Dumaresq).

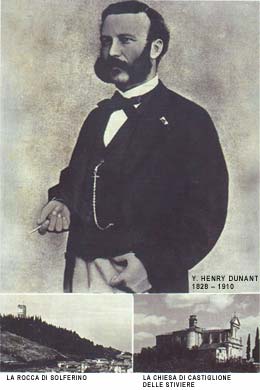

Henry Dunant – winner of the first Nobel Peace Prize, 1901

The newly founded organisation and his humanitarian efforts, brought Dunant prominence and acclaim, but his business affairs had been neglected and failed miserably. When Dunant was forced into bankruptcy, many fellow Genevans also lost their investments. In 1867 he resigned as secretary of the International Red Cross and left Geneva, never to return. In the ensuing decades, he lived a destitute life, forgotten by the world. It is intriguing then to trace how Henry Dunant came to be awarded the very first peace prize in 1901 (an honour he shared with Frédéric Passy, founder and president of the first French society for peace).

During the history of the peace prize, which stretches over more than a century, campaigns for particular candidates have often been conducted by individuals and organisations. Their intention is to sway the Norwegian Nobel Committee in its choice of laureate. The first such campaign took place in 1901 for the benefit of Henry Dunant. The 1901 award is particularly important because the Nobel Committee chose a course it would often follow later on. Dunant’s co-laureate, Frédéric Passy, was chosen for his traditional peace efforts, fully in line with Alfred Nobel’s will. The grounds for his candidacy were so evident, that a campaign was unnecessary. Most observers assumed that he would receive the first peace prize alone because he stood out as the eldest and foremost representative of the international peace movement. Dunant, on the other hand, was primarily honoured for his humanitarian efforts. Thus, two main categories of laureates were created in 1901.

Henry Dunant was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by an impressive array of individuals and organisations. Among them were ten professors from Amsterdam and Brussels, 92 Swedish parliamentarians and 62 parliamentarians in Württemberg, along with the board of the International Peace Bureau. In Norway, the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association had prevailed upon the chairman of the Nobel Committee to nominate Dunant. In addition, two Norwegian cabinet members had nominated him on behalf of the Norwegian Women’s Voting Rights Association. But it was primarily the efforts of the Norwegian military physician, Hans Daae, that would be decisive. Daae had become well acquainted with Dunant’s work through an article by the Swiss editor, Georg Baumberger, on the founder of the Red Cross in 1895, and the work of the German teacher Rudolf Müller. Dunant emerged from obscurity as a result of this, and in the late 1890s he received a number of honours and awards. Moreover, Bertha von Suttner, 1905 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, published Dunant’s article “A small arsenal against militarism” in her periodical Die Waffen Nieder! (Lay Down Your Arms!). Hans Daae advocated with success Dunant’s candidacy, and the Nobel Committee was convinced. Dunant was awarded the 1901 Nobel Peace Prize jointly with Frédéric Passy.

The announcement that the founder of the Red Cross had been chosen as peace laureate met with mixed reactions. Dunant had been awarded the prize for ameliorating the suffering of wounded soldiers, not for organising peace congresses or reducing standing forces, as stipulated in Alfred Nobel’s will. The Nobel Committee had chosen a broad interpretation of the provision that a laureate should “further fraternity between nations”. Critics of the award maintained that humanising war made it less destructive in most people’s awareness. Bertha von Suttner proclaimed that improving the laws of war was like regulating the temperature when boiling someone in oil. And the organisation Weltverein für obligatorische internationale Friedensjustitz in Berlin, in a letter to the president of the Storting (the Norwegian national assembly) dated 20 December 1901, wrote that the Nobel Committee had seriously violated Alfred Nobel’s will by awarding the peace prize to Dunant, who had merely made war better (qui a perfectioné la guerre).

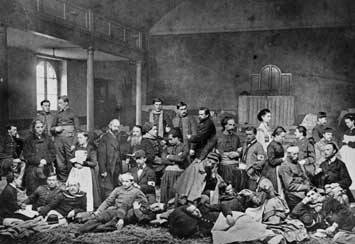

Franco-Prussian War, 1870-1871. Photo shows wounded French internees at the Marterey church, Lausanne, Switzerland.

After receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, Dunant continued to live a frugal life in a nursing home in the Swiss town of Heiden. Hans Daae saw to it that the prize money eluded the grasp of Dunant’s creditors; it remained untouched in a Norwegian bank at the time of Dunant’s death in 1910. His will bequeathed half of the prize money to the Norwegian Red Cross and the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association. The other half was donated for humanitarian purposes in Switzerland. The peace prize helped Dunant regain his dignity, and the favourable attention received by the Red Cross organisation bolstered its work in the years that followed.

The 1917 Nobel Peace Prize: the decision-making process

The Norwegian Nobel Committee decided not to award a peace prize after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The official explanation was that no worthy candidates had been nominated. But in 1917, the Nobel Committee chose a particularly deserving candidate: the International Committee of the Red Cross. Let us examine how key persons played a part in this award.

An influential French lawyer, Professor Louis Renault, was the driving force in extending the Geneva Convention to apply to maritime warfare. The revised convention was adopted in 1906. Renault was awarded the 1907 Nobel Peace Prize, and in 1916 he was elected president of the French Red Cross. In January of the next year, he drew up his nomination for the International Committee of the Red Cross.** The nomination was backed by such leading French authorities as the 1909 laureate, Baron d’Estournelles de Constant, professor of law Charles Lyon-Caen and representatives from the Institute of International Law, which as 1904 laureate had been the first organisation to receive the peace prize. In addition the Swiss Government nominated ICRC with a strong motivation.

The 1917 Nobel Peace Prize: The nomination and its motivation

In its nomination, the Swiss Government highlighted the efforts of the Red Cross before the war broke out, drawing special attention to the International Prisoner-of-War Agency, which had been set up in August 1914. The Red Cross had also helped transport soldiers who were ill or wounded to their home countries via Switzerland. The Swiss Government pointed out as well how the International Committee of the Red Cross unceasingly reminds the world that “the people who are now killing each other are brothers after all, and only peace can bring them the happiness they all yearn for.”

The French nomination declared: “We believe that few men (…) have done mankind so many services, and to such an extent contributed to the improvement of relations between peoples, as the zealous men who comprise the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva.” To which Louis Renault added: “As President of the French Red Cross I bear personal witness to this”.

There can be little doubt that the Red Cross relief work for prisoners of war weighed most heavily when the Nobel Committee reached its decision in 1917. In his report on the Red Cross to the members of the Nobel Committee, Secretary Moe placed great emphasis on these achievements. He drew attention to the international Red Cross conference in Washington in 1912, which had resolved that while peace prevailed, the national Red Cross societies should set up commissions to deal with the issue of prisoners of war. The ICRC in Geneva was to coordinate this activity and, in times of war, distribute collected funds to the benefit of prisoners of war.

The main task of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency was to procure information on prisoners of war and relay this information to their next of kin. From 1915 the Agency was granted permission to direct enquiries to camp commandants and the heads of hospitals and field hospitals. Hundreds of people – many of them volunteers – worked in Geneva to obtain information on prisoners of war. By June 1917 the office had sent nearly 800,000 communiqués to families in warring countries. The Geneva office delegated authority for prisoners from the Eastern Front to the Danish Red Cross.

The reactions to the 1917 award were favourable. Granted, there were references to the paradox that the Red Cross nursed wounded soldiers back to health so that they could be sent to their death once more, but the Red Cross could not be held responsible for this. And the experiences of the First World War had consequences for the Geneva Convention. It was revised in 1929 to include provisions on the treatment of prisoners of war and the protection of civilian aircraft in times of war.

World War I. Photo shows a delegate (center) of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) visiting a camp of German prisoners of war in Morocco.

The 1944 Nobel Peace Prize: humanitarian activities and services to prisoners of war

As in 1914, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided not to award the peace prize when the Second World War broke out in 1939. The next award was in 1945, when two peace prizes were conferred on 10 December, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. The reserved 1944 prize was awarded to the International Committee of the Red Cross, while the 1945 Nobel Peace Prize was bestowed on former US Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

The International Committee of the Red Cross had been nominated for the peace prize in 1940, and as the war drew to a close its candidacy gained impetus. In 1944 Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, chairman of the Swedish Nobel Foundation board, and Birger Ekeberg, president of the Court of Appeals in Stockholm, were among those who nominated the ICRC. They were joined by Martin Tranmæl, who was a member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, a leader in the trade union movement and editor of the Labour party-affiliated newspaper, Frede Castberg, Norwegian professor of law, and British Member of Parliament Philip Noel-Baker, who would himself be the laureate in 1959.

Birger Ekeberg drew attention to the wartime contributions by the ICRC in the service of humanity and for reconciliation, emphasising its services to prisoners of war, its relief work in occupied countries and its appeals to the belligerents to observe international law. In his proposal, Noel-Baker wrote: “In their work for the wounded, for prisoners of war and for help to starving populations, the International Red Cross Committee’s delegates have not only upheld the great traditions which they built up in earlier times, but have far surpassed the record of achievements and services to mankind which they have previously established”. Frede Castberg was the only one to mention the ICRC’s support for political prisoners in Germany and in areas occupied by the Germans, a topic he would be able to develop further when he was asked to write the report on the ICRC for the Norwegian Nobel Committee. He submitted his report in the autumn of 1945. What did Castberg bring to the fore?

World War II. Palais du Conseil Général. Central Prisoners of War Agency, Geneva, Switzerland.

The 1944 Nobel Peace Prize: aid to political prisoners

In his report on the ICRC’s work for prisoners of war, Castberg described the Red Cross inspections in the prisoner camps in detail. He also pointed out that the ICRC never directed a protest to the governments of the Axis powers, although there were certainly grounds for one. Castberg accounted for the ICRC policy as follows: “The Red Cross must be assumed to have found it wisest to exercise the utmost caution in order not to risk a breach of relations with Germany, which would have meant a complete halt to ICRC activities in Germany and German-occupied areas.”

Castberg used the same explanation in describing the role of the Red Cross in relation to civilian prisoners. Until mid-1942 the Germans denied the ICRC any intervention on behalf of this group, claiming that this was a police matter not subject to the provisions of the Geneva Convention of 1929. Not until the winter of 1942-43 did the Nazis allow civilian prisoners to receive Red Cross parcels containing food and medicine. These parcels brought succour to at least some of the concentration camp prisoners.

Research carried out in the 1980s has probed the ICRC’s relationship to Nazi Germany in light of the extermination of the Jews. Shortly after the Nazis had adopted their “final solution” to the “Jewish question” at the Wannsee Conference in 1942, the leaders of the International Red Cross were informed of their plans. That same autumn the leaders of the ICRC deliberated on whether they should publicly condemn the atrocities, but they chose to remain silent. The ICRC maintained its policy of caution in relation to the Nazis until the war was over, presumably because a public condemnation could result in reprisals against civilian and military prisoners. Moreover, cooperation between the Swiss government and Germany could be endangered. At worst it could have provoked military action against the neutral country of Switzerland.

When the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz was commemorated in 1995, the President of the ICRC, Cornelio Sommaruga, said that the organisation was fully aware of the gravity of Holocaust and the necessity of keeping its memory alive, in order to prevent its recurrence. He apologised for the errors and shortcomings that the Red Cross could be blamed for with regard to the victims of the concentration camps.

The Nobel Peace Prize 1963: A centenary celebration and a new Daae campaign

The year 1963 marked the 100th anniversary of the founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross; and as that year approached, Anders Daae, son of the military physician Hans Daae, decided to replicate his father’s successes from 1901 and 1917. Anders Daae had been active in the Norwegian resistance movement during the Second World War, which resulted in his arrest and deportation to Germany. There he experienced the heaviest Allied bombing raids on Berlin. As a prisoner he learned to appreciate the work of the Red Cross, often witnessing that the organisation’s work saved the lives of fellow prisoners.

A year and a half before the 1963 Nobel Peace Prize was to be awarded, Anders Daae initiated his campaign. He wrote articles about Henry Dunant and the Red Cross in Norwegian newspapers. He contacted fellow prisoners from the war years and succeeded in persuading all the incumbent members of the Norwegian Storting, who had been prisoners in Germany, to nominate the ICRC. He also enlisted four professors at the University of Oslo to nominate the organisation. Then he travelled to Stockholm and Copenhagen and convinced 91 Swedish and 15 Danish parliamentarians to back its candidacy. Finally, Anders Daae went to the Norwegian Nobel Institute, where he personally handed over the nominations and lists of signatures. This Daae campaign, like his father’s previous ones, was a success.

The 1963 Nobel Peace Prize: two branches of the Red Cross family

In 1963 the International Committee of the Red Cross was awarded the peace prize jointly with the League of Red Cross Societies. The League, which was established in 1919 at the initiative of an American named Henry P. Davison, is a federation of all the national Red Cross societies. The task of the League is to coordinate humanitarian work carried out by the national Red Cross societies on an international basis during times of peace, such as relief aid for refugees and emergency assistance in response to natural disasters. In 1993 the League was renamed the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Logo of the 125th anniversary of the Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent.

When presenting the award on 10 December 1963, Carl Joachim Hambro, member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, highlighted the humanitarian work of the two Red Cross organisations in times of war and peace and pointed out that the ICRC had spread awareness of the principles of the Red Cross and the provisions of the Geneva Conventions. Hambro also drew attention to the work of the ICRC in amending and extending the Geneva Conventions, most recently the revised conventions of 1949. For the first time, the conventions provided for the protection of “civilian persons in time of war”. Finally, Hambro mentioned the efforts of the ICRC at the time of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and during conflicts in Algeria, Congo and Tibet. In describing the worldwide humanitarian work of the League, Hambro concluded that “the cooperation between the Red Cross Societies of ninety different countries of different races, creeds, and color is of very real importance for international understanding and peace.”

Conclusion

The Red Cross has a unique position in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Committee’s choice of Henry Dunant as 1901 laureate was a direct recognition of the role of the ICRC in promoting peace. In this light, it is nearly justifiable to call the Red Cross a “four-time recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

Henry Dunant’s great idea has given results. In 2003 the ICRC had more than 1,200 doctors, nurses and engineers on field missions all over the world, assisted by 9,000 local employees. The National Societies of Red Cross and Red Crescent had 97 million members and volunteers, 300,000 employees, assisting some 233 million beneficiaries.

From the very beginning, the Norwegian Nobel Committee interpreted Alfred Nobel’s will in a manner that made it possible to award the peace prize for humanitarian work. In light of the two world wars of the 20th century, it was natural for the Nobel Committee to choose the Red Cross as laureate in 1917 and 1944. By honouring the League of Red Cross Societies jointly with the ICRC in 1963, the Norwegian Nobel Committee made it clear that efforts to aid the needy also play an important role in building peace.

Bibliography

Archives of the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo (nominations, correspondence, press clippings).

Redegjørelse for Nobels Fredspris 1901 – 1950. (Reports of the advisers, available only in Norwegian.) The Norwegian Nobel Committee, Oslo.

Nobel Lectures: Peace 1901-1970. Frederick W. Haberman, ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1972.

Libæk, Ivar. The Nobel Peace Prize: some aspects of the decision-making process, 1901-17. The Norwegian Nobel Institute Series, Vol. 1 – No. 2, Oslo 2000.

Abrams, Irwin. The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1988.

Dunant, Henry. A Memory of Solferino. 1862.

Øivind Stenersen, Ivar Libæk and Asle Sveen. The Nobel Peace Prize: One Hundred Years for Peace. Laureates 1901-2000. Oslo: Cappelen, 2001.

Homepage of the International Committee of the Red Cross

* Ivar Libæk (1949-) obtained his cand. philol. in history at the University of Oslo in 1975. He has more than twenty years of experience as teacher in senior secondary schools, and has taught and acted as examiner at the University of Oslo. Since 1980, he has written textbooks in history for primary and secondary school levels. Libæk is co-author of the books The History of Norway from the Ice Age to Today and The Nobel Peace Prize: One Hundred Years for Peace.

In the period 1999-2001, Libæk was Nobel Institute Fellow, and is now Project Advisor at The Nobel Peace Center in Oslo. He has published articles in The Norwegian Nobel Institute Series on the Nobel Peace Prize and the Norwegian Nobel System.

** Professor Renault cooperated closely with the secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Ragnvald Moe, during this process. The two men met in Paris in the autumn of 1916 and discussed the work of the Red Cross. In January of the following year, Moe reminded Renault in a letter that the closing date for nominations was 1 February. By that time he had already known of the Swiss Government’s nomination. It was Moe himself who wrote the report on the Red Cross for the Nobel Committee, after consulting with Hans Daae, the man behind the award to Henry Dunant. At the ceremony on 10 December 1917, secretary Moe himself gave the speech, in which the Norwegian Nobel Committee reviewed the history and the activities of the Red Cross.

First published 30 October 2003