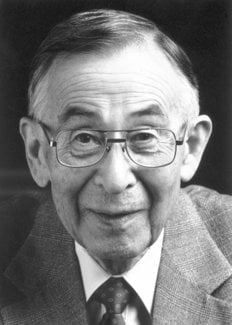

Charles J. Pedersen

Biographical

I was born in Pusan, Korea, on October 3, 1904. My father Brede Pedersen, was a Norwegian marine engineer who left home as a young man and shipped out as an engineer on a steam freighter to the Far East. He eventually arrived in Korea and joined the fleet of the Korean customs service, which was administered by the British. Later, he abandoned seafaring and became a mechanical engineer at the Unsan Mines in what is now the northwestern section of present-day North Korea.

My mother, Takino Yasui, was born in 1874 in Japan. She had accompanied her family to Korea when they decided to enter large-scale trade in soybeans and silkworms. They established headquarters not far from the Unsan Mines, where she met my father. I had a sister, Astrid, five years my senior, and an elder brother who died in childhood prior to my birth.

The Unsan Mines were an American gold and lumber concession, 500 square miles in area. Because the mines were administered by Americans, there was an effort to make life there as American as possible. English was the spoken language, and it was the language I learned as a child. Foreign language schools did not exist in Korea at that time and so at the age of 8 years I was sent to Japan to attend a convent school in Nagasaki. When I was 10 years old my mother took me to Yokohama, and I began my studies at St. Joseph College. St. Joseph’s was a preparatory school run by a Roman Catholic religious order of priests and brothers called the Society of Mary, also known as the Marianists. There I received a general secondary education and took my first course in chemistry.

When it came time for university, I chose, with my father’s encouragement, to study in America. I selected the University of Dayton because it was in Ohio were we had family and friends and because it too was run by the Society of Mary. After taking a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering at the University of Dayton, I went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where I obtained a master’s degree in organic chemistry. I did not remain at MIT to take a Ph.D.; I was still being supported by my father, and I was anxious to begin working. In 1927, I obtained employment at the Du Pont Company in Wilmington, Delaware, through the good offices of Professor James F. Norris, a very prominent professor and my research advisor. At Du Pont, I was fortunate enough to be directed to research at Jackson Laboratory by William S. Calcott. I remained at Du Pont for my entire 42-year career as a chemist.

As a new scientist I was initially set to work on a series of typical problems, which I solved successfully. After a while, I began to search for oil-solvable precipitants for copper, and I found the first good metal deactivator for petroleum products. As a result of this work, I developed a great interest in the affects of various ligands on the catalytic properties of copper and the transition elements generally and worked in the field for several years.

I next expanded my interests in the oxidative degradation of the substrates I was working on, namely petroleum products and rubber. By the mid-1940s I was in full career, having established myself in the field of antioxidants and independent in terms of the problems I might choose. In 1947, I was appointed research associate, then the highest title that a Du Pont Company researcher could attain. Also at that time, I married Susan Ault and settled in the town of Salem, New Jersey, where I have lived ever since.

During the late ’40s and ’50s my scientific interests became more varied. I became interested in the photochemistry of some new phthalocyanine adducts and of quinoneimine dioxides. I developed polymerization initiators and even made some novel polymers. In 1960 I returned to investigations in coordination chemistry, and decided to study the effects of bi- and multidentate phenolic ligands on the catalytic properties of the vanadyl group, VO. In the course of these investigations one of my experiments yielded an unexpected small quantity of unknown white crystals which I eventually identified as dibenzo18-crown-6, first crown ether. The last nine years of my career were spent in the further study of crown ethers. I retired from Du Pont in 1969. During my retirement, I have pursued interests in fishing, gardening, bird study and poetry.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Charles J. Pedersen died on October 26, 1989.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.