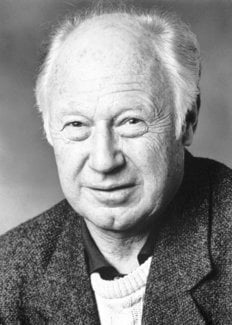

Michael Smith

Biographical

I was born on April 26th, 1932 at 65 St. Heliers Road, South Shore, Blackpool, England in the house of my maternal grandmother, Mary Martha Armstead, having been delivered by the District Nurse, Ms. Parkinson, a lady who I can remember from my infant and juvenile days in her uniform and navy blue raincoat on her bicycle doing her rounds and visiting schools for health inspections. My parents, Mary Agnes Smith and Rowland Smith, both had to work since their early teens, she in the holiday boarding house of her mother and he in his father’s market garden in Marton Moss, a village on the south side of Blackpool, just north of Saint Anne’s-on-Sea. I went to the local school, Marton Moss Church of England School for 6 years from the age of 5. My mother attended the local church, Saint Nicolas, and consequently I attended that church and its Sunday School. My only prizes from the Sunday School were “for attendance”, so I presume my atheism, which developed when I left home to attend university, although latent, was discernible.

During my last year at elementary school, 1943, I sat for the “Elevenplus” examination which was used in the English schools in those days. In principle, of course, it was an invidious system designed to identify the approximately 20% of the school population that would be offered an academic education and the 80% who would be obligated to take a secondary education that terminated with no further academic options at age 15 (of course, there was the alternative of private schooling, but that was not an option if you were the child of poor parents, as was I). I was lucky enough to obtain a scholarship to the local private school, Arnold School. I did not, at the time, consider this to be luck. I did not want to go to Arnold School because the pupils were considered to be snobs and I thought that I would be ostracized by my friends in Marton Moss. Luckily, my mother insisted, and I went to Arnold School. I cannot say it was the happiest time in my life (I was no good at sports, and proficiency in sport is important in private school life. And I hated the war-time meals that were provided at lunch, as well as the prefect who insisted that I eat the awful food). But the schooling was first-rate, and in this I flourished, although not equally well in all subjects. Clearly, science was my metier, and I was lucky to have a chemistry teacher, Sidney Law, who stimulated my interest in chemistry and who took a personal interest in me (he told me I should read a better newspaper than the one to which my parents subscribed and, as a consequence, I became a life-long reader of the Manchester Guardian. That, in turn, stimulated me to become a reader of the New Yorker as soon as I came to North America, another life-long addiction).

The seven years from 1943 to 1950 were also a time when I became a boy scout. That was a piece of luck. The headmaster at Arnold School, Mr. Holdgate, at the end of my first term, sent me to a dentist, Mr. Paterson, in the hope that he could correct my protruding front teeth, about which I had been teased by my schoolmates. Mr. Paterson did not correct the problem with my teeth but he did introduce me to a wonderful scoutmaster, Mr. Barnes, who inducted me into the happy world of camping and outdoorsmanship which provided me with enjoyment and vacations throughout my secondary school years and right up to the present. An enjoyment that explains why I have a particular delight in living amid the rugged outdoors and beauty of British Columbia.

The second World War impinged on the lives of many of us who were alive at the time. Blackpool, as it turned out, was a very safe place, being in the northwest of England and distant from the targets for German bombing. The large number of hotels and boarding houses in this seaside resort were used to house military trainees, mainly for the airforce. And my father, working his father’s market garden, grew primarily food crops rather than his preference, chrysanthemums. Occasionally, bombers, presumably diverted from their primary targets of Manchester and Liverpool, would try to bomb the new factory behind our house that produced Wellington bombers. Usually, they hit the market gardeners’ greenhouses which showed up better at night. And I remember one night, alone in the house with my baby brother Robin, when a stick of bombs fell on either side of the house.

I was not proficient in Latin and so was not able to go to Oxford or Cambridge. However, I did enter the first-rate chemistry honours program at the University of Manchester in 1950, where the professors were E.R.H. Jones and M.G. Evans, and graduated in 1953, with the financial support of a Blackpool Education Committee Scholarship. I had hoped to get a firstclass degree, but only got a 2(i)! I was very disappointed. However, I still was able to obtain a State Scholarship which supported me throughout my graduate studies until I finished my Ph.D. degree in 1956. My supervisor was H.B. Henbest. He was an outstanding young organic chemist, and I was glad to have him as a supervisor of my work on cyclohexane diols. However, we did not have a particularly warm relationship. I was socially shy and moody and was probably quite hard to understand.

The last year of our graduate studies saw me and my classmates writing to various American professors seeking post-doctoral fellowships. I had no luck in obtaining my desire of a fellowship on the west coast of the United States, but I heard, in the summer of 1956, that a young scientist in Vancouver, Canada, Gobind Khorana, might have a fellowship to work on the synthesis of biologically important organo-phosphates. While I knew this kind of chemistry was much more difficult than the cyclohexane stereochemistry in which I was trained, I wrote to him and was awarded a fellowship after an interview in London with the Director of the British Columbia Research Council, Dr. G.M. Shrum.

I arrived in Vancouver in September 1956. My first project was to develop a general, efficient procedure for the chemical synthesis of nucleoside-5′ triphosphates based on the synthesis of ATP by Khorana in 1954. This study led to more extensive investigations of the reactions of carbodumides with acids, including phosphoric acid esters and to a general procedure for the preparation of nucleoside-3′,5′ cyclic phosphates, a class of compounds whose existence and great biological significance had only recently been discovered. One particular pleasure of that period was the development of the methoxyl-trityl family of protecting groups for nucleoside-5′-hydroxyl groups (one synthesis of trimethoxytritanol erupted and left a large orange stain on the laboratory ceiling); this class of protecting group is still in use in modern automated syntheses of DNA and RNA fragments.

In 1960, the Khorana group, including myself, newly married (I have three children, Tom, Ian and Wendy. My wife Helen and I separated in early 1983), moved to the Institute for Enzyme Research at the University of Wisconsin. There I worked on the synthesis of ribo-oligonucleotides, that most challenging of chemical problems for a nucleic acid chemist. Early in 1961, I began to realize that it was time to move on. Helen and I wanted to return to the West Coast of North America, and I accepted a position with the Fisheries Research Board of Canada Laboratory in Vancouver. I enjoyed my time there because of the opportunity it presented to learn about marine biology and I was able to sustain my interest in nucleic acid chemistry because of the award of a U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant, which led to a new synthetic method for nucleoside-3′,5′ cyclic phosphates. However, the atmosphere of the laboratory, although based on the campus of the University of British Columbia, was not really conducive to, or supportive of, academic research. Hence, in 1966, I was very glad that Dr. Marvin Darrach, then Head of the Department of Biochemistry, offered to nominate me for the position of Medical Research Associate of the Medical Research Council of Canada. This award, which provided salary support, allowed me to become a faculty member of the Department, my academic home ever since, except for sabbaticals at Rockefeller University, the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of the Medical Research Council in Cambridge and Yale University. The Council also has provided research grant support throughout my academic career.

In 1981, Ben Hall and Earl Davie, of the University of Washington, invited me to be a scientific cofounder of a new biotechnology company, Zymos, which was funded by the Seattle venture capital group, Cable and Howse. One of the first contractors was the Danish pharmaceutical company, Novo, who asked Zymos to develop a process for producing human insulin in yeast. After a considerable cooperative effort by Zymos and Novo researchers a successful process was developed. In 1988, the pharmaccutical company, now Novo-Nordisk, purchased outright the biotechnology company, now named ZymoGenetics. I am pleased that, although I no longer have any involvement, ZymoGenetics has subsequently expanded and has continued research on a wide variety of potential protein pharmaceuticals.

In 1986, I was asked by the then Dean of Science at the University of British Columbia, Dr. R.C. Miller, Jr., to establish a new interdisciplinary institute, the Biotechnology Laboratory. I decided that it was time for me to start paying back for the thirty years of fun that I had been able to have in research. I have very much enjoyed recruiting and helping to get established the group of young faculty members that constitute the core of the Biotechnology Laboratory. I also have enjoyed being Scientific Leader of the National Network of Centres of Excellence in Protein Engineering that was funded in 1990. It has been very satisfying, in this case, to see established scientists, working in the various subdisciplines of biochemistry, come together in nation-wide collaborations to solve important problems in protein structure-function analysis and to work with Canadian industry in improving technology transfer which has been less than optimal in the past.

One difflcult chore was presented to me in 1991 when I became Acting Director of the Biomedical Research Centre, a privately funded research institute on the Campus of the University of British Columbia. Its source of funding disappeared; therefore I had the responsibilities of managing the Centre on a tight budget, negotiating future funding from the Provincial Government, and helping to ensure the transfer of ownership to the University. This task was made difficult because many of the staff had been led to believe that I was trying to take over and subvert the activities of the Centre. This misguided belief helped the problems of the Centre to become a public political football in an election year. However, funding was negotiated, the University took over the ownership and I was able to step down after 12 months with the Centre and its mission intact.

I look forward to shedding all my administrative responsibilities in another couple of years and returning to my first scientific love, working at the bench and having more time for sailing and for skiing.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Michael Smith died on October 4, 2000.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.