Interview with Jennifer A. Doudna, February 2021

“Embrace your interests, your passions, and really give it your all!”

We spoke to biochemist Jennifer Doudna on the International day of Women and Girls in Science, 11 February. Her collaboration with fellow laureate Emmanuelle Charpentier and her reaction to receiving the Nobel Prize were two topics that were up for discussion.

Why did you decide to pursue science?

Jennifer Doudna: I loved math when I was growing up. Nobody in my family was a scientist, but my father loved doing puzzles. So we did a lot of puzzles. I was growing up in a small town in Hawaii and I loved the natural environment there. I found myself fascinated by the evolution of plants and animals that survived in that native island environment. This was long before I knew anything about DNA, but I thought it was so interesting that I wondered about the chemistry of natural systems and natural organisms. I decided I wanted to be a chemist. Then when I learned about biochemistry, I thought that’s what I really want to do. I want to study the chemistry of living things. I set off on that journey in college and kind of never looked back.

Did you have a particular person, a mentor or role model, who really influenced you?

I would say it’s probably first and foremost my father, because even though he was not a scientist, he was very interested in science and he read everything. He was an avid reader and a literature professor. He gave me lots of books. He gave me Jim Watson‘s book about the double helix as well as books by Harold Morowitz and a lot of classic writers who wrote about science for a non-scientific audience. He really encouraged me early on to pursue my interests. Later when I was in grad school, he was the one person in my family that when we got together, his first question would always be, ‘What are you working on in the lab?’ He would really want to know, like he didn’t just want a one sentence answer. He really wanted to get into it. ‘What are you doing and why are you doing it? Why is it interesting?’ So that was great.

Beyond that, I did have some wonderful teachers. My biology and chemistry teachers in high school were very encouraging. I had multiple great professors in college who also encouraged my interest. My biochemistry professor in college gave me a chance to work in her lab over the summer, which was critical, where I really figured out, ‘Wow! I love lab work. This is really great. This is exactly what I want to be doing.’ When I got to grad school, I really got lucky. I got into a lab of a wonderful person who now is a Nobel Laureate himself, Jack Szostak. He was an incredible mentor, very passionate about science and encouraging for all of us that were in the lab at the time. I feel like I really lucked out.

The Nobel Prize medal and diploma were presented to chemistry laureate Jennifer A. Doudna at her home in Berkeley on 8 December 2020.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Brittany Hosea-Small.

Were you influenced by your father to be an avid reader too?

I have to say that in the roughly 10 years that I was pretty intensely working on CRISPR (like up until this year or 2020) I had to put a lot of things on hold. I’m an avid gardener and I gave up my garden. And I really stopped reading for pleasure. I had to mostly just read for work. Even trying to keep up with the scientific literature was very difficult. During that period of time, I had a young son, my mom was ill and then passed away. So we’re dealing with that. I was made division head in my department so I had a lot of administrative duties there. There’s this bunch of stuff. I really put all of that on hold.

What was really interesting for me was that last year in 2020, besides the year of this Nobel Prize, it was the year of the pandemic beginning. I think, like many people, I had to change many things about my lifestyle. I stopped travelling – I used to travel every week. Then I found that last spring, I just started slowly thinking, ‘Gee, I really ought to be composting.’ I started composting in my garden and that’s what took me up into my garden regularly. I started pulling a few weeds and pretty soon I had a very beautiful and active garden again. I loved it. I was in my garden every day and I had vegetables, flowers, fruit and lemons. It was really fun and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I don’t want to give that up again. You know, that’s too much.’ It was the same thing with reading.

There were a lot of very disturbing things going on in the US politically, so I had a number of sleepless nights. I found myself picking up books to help me kind of get through it. I love reading novels. I love reading science books. I love reading things that don’t have anything to do with work because I just I’m interested in them. Both the gardening and the reading are things that came back to me during the pandemic, and I’m going to fight to keep it in my life as we kind of slowly go back to “normal”.

How do you cope with failure and with unexpected problems?

I sort of have three ways of coping. The first is that I always remind myself to take a long view of things; something that’s frustrating or disappointing in the moment, is it frustrating today or next week? I try to think about, ‘How am I going to feel about this in six months or a year from now, or 10 years from now?’ I also ask myself, in the scheme of problems in world, how big is this problem. Often it’s not very big. I try to remind myself of the context and I try to remember all the things I’m grateful for. I’m fortunate that I have a family, that I’ve had the successes and I’ve had my career.

That takes me to the second thing; I do really rely on friends, family and colleagues and I’ve been so fortunate to have a really great network of people who I rely on for support. I guess I actively now, even more than when I was younger, look for people that are going to be supportive and who I can in turn be supportive for as well. People that you can really build strong relationships with, I think is very valuable.

The third thing is because there was certainly some adversity when I was growing up in Hawaii, it sounds like a paradise, but it wasn’t. There were a number of issues when I was growing up. I had to learn to rely on myself. I had to kind of find an internal strength to deal with bullying, to deal with all kinds of name calling and resentment. I feel like I go back to that now, too. I kind of go to my inner core and I know that there’s a part of me that no one can touch and that no matter what happens, I know that I know who I am. I know what I value. If there’s adverse things going on there, there’s a part of me that no one can touch that way. That gives me some strength as well.

Do you have any advice for young researchers or students?

I honestly think the most important advice is to go for it. That means to embrace your interests, your passions, and really give it your all. I think that is what I’ve seen both for myself and [other] people. People that I’ve had the pleasure to work with in my laboratory, the most successful of them are people who are able to deal with their fears. We all have fears but sometimes you try something and there is failure, right? You have to deal with that.

I think for me and for people that I’ve seen that are highly successful, they deal with that. Each of us has to find our own way to deal with that as we just discussed. But I just think you have to embrace your passions. You have to really go for it. People that have been less successful in my opinion, are those that dabble in something, but then don’t really give it their all. They almost never give themselves a chance to succeed, as they back off too soon. I think for young people, I tell them go for it, find supportive mentors who will help you through the tough times, and then just keep going. Because if you have a good idea, it’s probably going to work out in some way. You may not be able to predict how, but you should just keep pursuing it.

Today it’s the International day for Women and Girls in Science. Do you think diversity is important in science?

Diversity is really important in science. First of all, I think that if you want to have the best scientific outcomes, you need a lot of different brains working on it. We all come to science (or anything really) with different perspectives, skill sets, interests, passions and ways of approaching a problem. The more of that we have, I think the more likely there is to be interesting science that gets done and frankly, interesting solutions to real problems. The pandemic is one very real example we’re dealing with right now where thank goodness there was creative work done years ago on using mRNA delivery. And now we have these wonderful vaccines, but it came together very quickly.

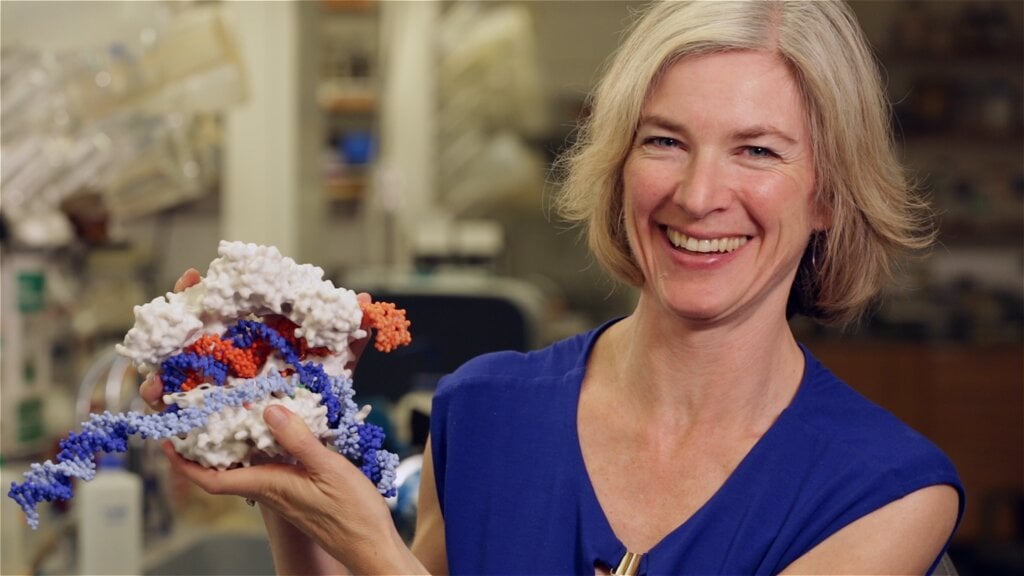

Nobel Prize-winning UC Berkeley biochemist Jennifer Doudna with a model of CRISPR-Cas9. Doudna spoke about the gene-editing process with Radiolab podcast in 2015.

Photo credit: UC Berkeley photo by Stephen McNally

Do you have any specific advice to young girls who want to go into science?

I would never want to stereotype, but I do think there’s more of a tendency by women and girls to underestimate themselves: ‘well, you know, I shouldn’t apply for that job or fellowship or graduate program because I’ll never get in.’ I feel like I hear it more frequently from my female trainees than from male. I don’t know all the cultural reasons for that, but I think it’s something that as women, we have to actively encourage both ourselves and other women and girls that might be following in our footsteps to actively put that little voice aside and trust that actually they’re probably better than they think they are.

Tell us about the first time you met your co-laureate Emmanuelle Charpentier.

She and I were both invited to a meeting in Puerto Rico in the spring of 2011. This was a conference sponsored by the American society for microbiology meeting that she might very reasonably be invited to. But for me, not so much because I’m really not a microbiologist at all. It just so happened that they were having one session on CRISPR, which at the time was a fairly esoteric area of microbiology, but interesting.

A friend and colleague, John, was at this conference and he said to me, ‘Oh, Jennifer, I’d love to introduce you to Emmanuelle.’ I had read her paper in Nature and it was a really nice work. I thought it’d be really interesting to talk to her. When I got introduced to her, she was this very chic woman that is quite petite and very attractive. I was immediately impressed by her kind of stylish, very natural look and fashion sense, not fancy but just really nice.

She said that she really had been looking forward to talking to me and I thought, ‘Oh, that’s cool.’ We had our session and then we went for a meal. She said, ‘Hey, I’d love to talk to you about the possibility of doing some work together.’ We started walking around old San Juan. The atmosphere there feels almost a bit French or European. It has these cobblestone streets and is quite lovely. She and I were just walking around these streets and talking about this protein, which at the time was called Csn1 and later was renamed Cas9.

We were talking about the possibility of working together to figure out how it was able to work in bacteria, to defend against viruses. There was a hypothesis that it might be a DNA cutter, but nobody had demonstrated that. How it would recognise viral DNA was unclear. That was really the basis of our initial interactions.

How was it to work with Emmanuelle Charpentier?

I loved working with Emmanuelle. She always had a great sense of humour, kind of a very dry sense of humour, even in email. She would say things like, ‘Oh, Jennifer, you have to excuse my Frenchy English.’ And I would say, ‘Oh my god, I’m so jealous of your Frenchy English. I wish I had Englishy French!’

She was in Sweden at the time. She was up at Umeå University so she was nine hours ahead of California time. When we were working really intensely on analysing data and writing a manuscript together, it was almost like working 24/7 because I would go to bed and she’d be getting up and she’d be working. By the time I got up, there would be a whole new set of things for me to work on and look at. It was just really intense and really fun.

How did you hear about the Nobel Prize? What was your reaction?

I’m embarrassed to say, I’d had a very long day. This is the day before the surprise of when it was announced. I had been at an all-day meeting. I was very tired that night. Of course I was aware about the Nobel announcements being made, but I just didn’t really think too much about it. I turned the ringer off on my phone and I went to bed. I fell asleep and fell into it very deeply. I woke up at just before 3:00 am, California time. My phone was buzzing and I could see that somebody was calling and then there were some unanswered calls and messages. I picked it up and it was a reporter from Nature magazine who I know, Heidi Ledford.

She said, ‘Hi, Jennifer, sorry to bother you early. But I really wanted to be the first to ask you how you feel about the Nobel.’ I was literally coming out of a deep sleep and I said to Heidi, ‘Oh my god, I haven’t had time to look at the news. I don’t know who won it?’ And she said, ‘Oh my god, you haven’t heard!’

I honestly got very nervous. I started to think that I might be dreaming. I said, ‘I can’t talk to you right now. I feel like I need to hear this from somebody official.’ I hung up and another incoming call was coming in and it was Martin Jinek, who was the scientist who did the CRISPR/Cas9 research in my lab in collaboration with Emmanuel, calling me from Switzerland. I answered the call and he said ‘Jennifer, oh my god. It’s just so fantastic as this is so exciting.’ Honestly, I have to say at that moment I knew it was real. The reason is that Martin is the most down to earth and humble person on the planet, and for him to be calling me at three in the morning from Switzerland, with this news, I knew it had to be real. Then of course I got connected to the Nobel Foundation, but that was the first five minutes of my realisation.

Picture of Jennifer Doudna while she was receiving the news of her Nobel Prize in October 2020.

Photo credit: Brittany Hosea-Small

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

First published: February 2021

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.