David Baker

Interview

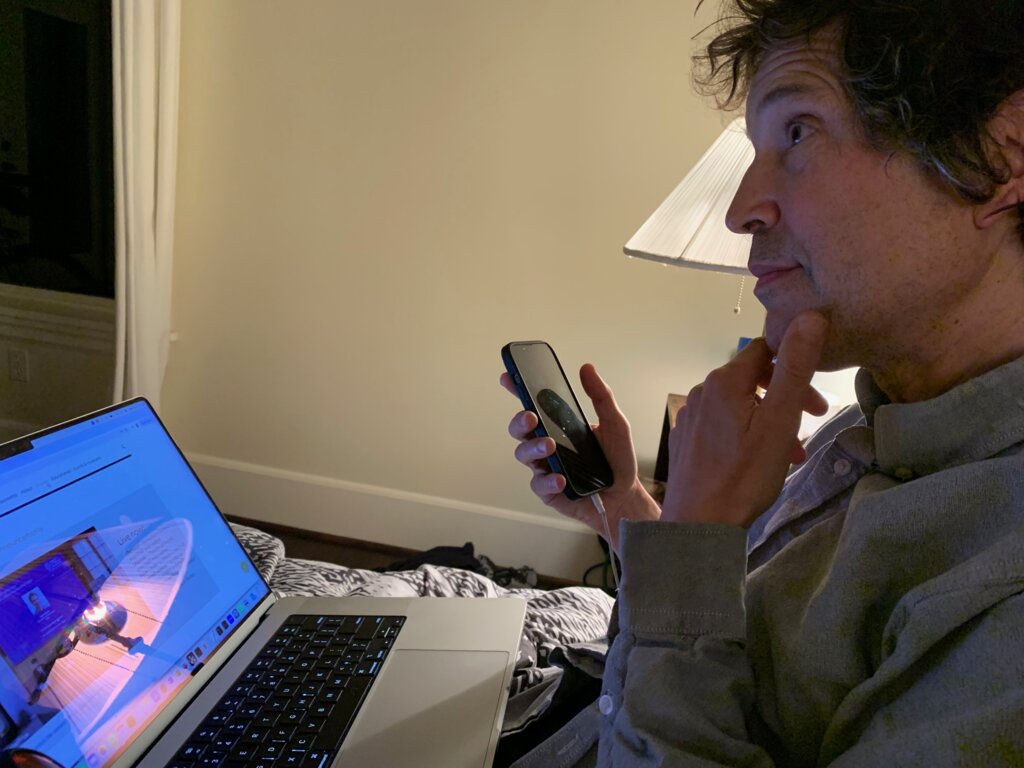

Interview, December 2024

Interview with the 2024 chemistry laureate David Baker, recorded on 6 December 2024 during Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

David Baker answers the following questions (the links below lead to a clip on YouTube):

0:09 – What influence did your parents have on you?

0:58 – How did you become interested in biology?

2:01 – Did you have a plan for your career?

2:49 – Why do you find proteins interesting to work with?

3:43 – How important is it for scientists to address the world’s biggest challenges?

4:10 – How does it feel when your work has an impact?

4:56 – Why is collaboration in science important?

6:30 – How important is diversity and representation?

7:15 – For you, what makes a good lab?

8:13 – Why is it important for science to be open access?

09:32 – How important is building a community among colleagues?

10:16 – Do you enjoy mentoring?

11:26 – How do you maintain your work-life balance?

12:50 – How do you keep going when nobody believes in your ideas?

14:19 – What message do you have to others that think outside the box?

14:42 – How do you deal with failure?

16:42 – What advice do you have for young scientists?

17:40 – How has AI transformed your research field?

21:17 – How did you celebrate receiving the Nobel Prize?

First reactions. Telephone interview, October 2024

“I will try to get some sleep, but I don’t know if it’s possible”

News of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry gave David Baker’s household a very early wake up call. Here, just after the prize announcement, he talks about the exciting potential of building brand new proteins, the inspirational effect his fellow laureates have had on his field and whether it is necessary to understand how predictive algorithms work.

Interview transcript

David Baker: Hello?

Adam Smith: Oh, hello. Is this David Baker?

DB: It is, yes. I’m still listening. I’m in the press conference.

AS: Oh, I do apologise. If you want to finish listening to the press conference, I can hang on,

DB: Let me just go through the rest of the press conference and then then we can talk. Would that be all right?

AS: Certainly. I’ll phone you back as soon as it’s finished.

DB: Hello?

AS: Hi, it’s Adam Smith again from the website of the Nobel Prize. Many congratulations.

DB: Thank you.

AS: Can you just tell me how the news reached you?

DB: Let’s see. Well, actually I think it’s kind of funny. I didn’t realise this till afterwards, but I think they had the phone number for my son who then gave them my phone number. And so I got a phone call, and my wife promptly started screaming, so I had a little hard time hearing, but then they got the news across

AS: I like that she twigged before you did.

DB: Yes.

AS: I mean, people always said there’d be a Nobel Prize for the people to solve the protein folding problem, and here it is. How does it feel?

DB: It is well, of course it’s a great honour and it is very exciting and it’s great to share this with Demis and, really John Jumper in particular, who really solved the classic structure prediction problem. You know, for protein design, I always thought that if there was a Nobel Prize, I’d be sharing it with Steve Mayo and Bill DeGrado. So I’m a little sorry about that. But yes, I think it’s neat to have you know, there’s always been two sides to the protein folding problem going from sequence to structure and then back from structure to sequence. And I think it’s neat that that there’s a Nobel Prize for them together.

AS: Yes, united. What do you think is going be the most beneficial effect of protein design in the foreseeable future?

DB: I’m really optimistic about really a wide range of applications. So just thinking about the things that we’re working on now, in health and medicine, I think smarter therapeutics that are more precise, and act only in the right time and place in the body, could get around a lot of the problems of systemic drugs. We have the first really de novo design medicine that’s been approved for use in humans. That’s a vaccine designed by my colleague Neil King at the Institute for Protein Design. Then outside of medicine, I think we’re making great strides now in developing new catalysts, and that could be for things like breaking down pollutants and plastics and things in the environment to coming up with sort of greener chemistry, you know, better routes to new molecules. I think there’s a lot of sustainability applications, you know, once you start just thinking about all the different things proteins do in nature that, and they really just evolved over random chance over, you know, over millions of years of natural selection. Now with the ability to design new proteins, specifically to solve problems there’s just so many possibilities. It’s really exciting.

AS: It’s a whole new world, isn’t it? Gosh.

DB: It’s a whole new world. Yes, it really is.

AS: Yes. Just lastly, on the protein folding question, how does it feel being awarded with basically your competitors? Because you know, for a while, RoseTTAFold and AlphaFold were sort of, you know, competing with each other. How does it feel to be united in this prize?

DB: I’ve never really felt that DeepMind or John or Demis were competitors. I think it was very inspiring. We were developing physically based methods for protein structure prediction and protein design for many years, and we were making progress on protein design and being able to design, you know, more complicated protein functions. But it was continued progress. But then, when John developed AlphaFold2, it was really kind of a wake up call for me to the power of deep learning, so rather than competitors, I really would say they’ve been great inspirers about the power of deep learning. I think that a lot of the most exciting things that we’ve done in the recent years have come from the deep learning methods that we’ve developed who really you know, really inspired that machine learning to have so much power in this field from John and Demis’s work.

AS: It may be too big a question for now, but as you said, basically the protein folding question was going be solved by understanding, but in the end it got solved by not understanding the rules. Does it matter that the rules are not understood? But it works?

DB: That’s a big question. I think for the many, many uses that protein structure prediction has had, that knowing protein structures have, it doesn’t really matter so much how you get there. And humans are very comfortable with solving problems every day with a very, very complicated neural network that we really don’t understand at all; our brain. We’re quite comfortable with the solutions we come up with, and we don’t have a lot of anxiety about not understanding exactly how our brains work.

AS: All fascinating. Thank you. Just for now, it’s crazily early in the morning there, what happens next?

DB: I think while we’ve been on the phone, I think I’ve had to decline about a hundred phone calls and the messages keep cropping up. I think I’m gonna try and get some sleep. I don’t know if that’s possible. But yes, it’s going to be quite a day.

AS: It will, it would put you among a select group of laureates who’ve managed to do that. So good luck. I hope it works.

DB: Yes, I’m not very optimistic, so … [laughs] it’s very exciting.

AS: Okay. Once again, congratulations David.

DB: Nice talking to you.

AS: Thank you. Bye. Bye.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.