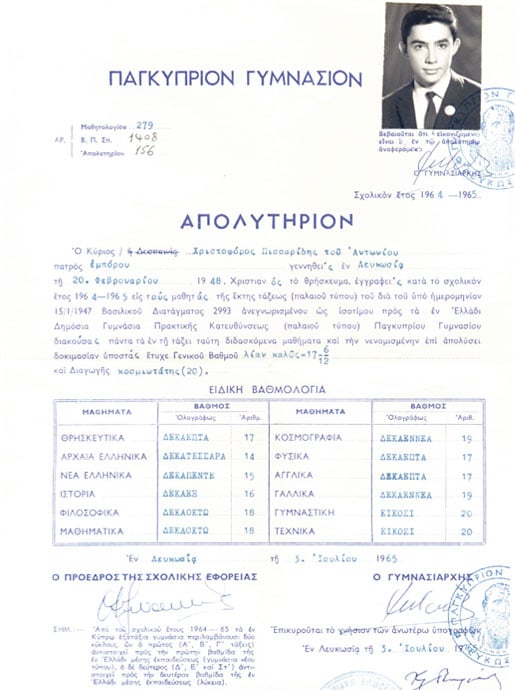

Christopher A. Pissarides

Biographical

I was born in Nicosia, Cyprus, on 20 February 1948. My father Antonios was born in the village of Agros, in the Troodos mountains, a village in a valley surrounded by mountains on three sides and with an opening to the south overlooking in the distance the bay of Limassol. He was one of seven children, and at the age of ten he was taken out of school and sent to Nicosia to work as a shop assistant for his uncle. He lived and worked with his uncle’s family until his twenties, when he was able to open his own shop, selling materials for making clothes and other items for the home. His business flourished when we were growing up but late in his life economic development and cheap imports made his trade obsolete.

My mother Evdokia Georgiades was born in Nicosia to a better-off family, and she went to French school, learning to speak fluent French and English. Her family also claimed their origins from the village of Agros. They got married in 1943 and had three children: my sister Maro, myself and my younger sister Anna. Despite her education, my mother stayed home to look after us. She also had home help from my father’s nieces from the village, who followed his steps and moved to town to find work. When my sisters and I left home she got a job as a shop assistant for one of her cousins, who had a thriving clothing business.

We were a happy family and I had a good upbringing. I have particularly fond memories of our family evenings at home before television, and our summers on the coast of Kyrenia and the mountains and valleys of Agros. I used to spend the time with my cousins, fishing in Kyrenia (mostly unsuccessfully) or playing in the riverbeds and springs of Agros. Cultivation in the village was still at subsistence level, in small plots, and occasionally we would stray into some vegetable patch or tomato bed, to be chased away by hard-working men and women in their traditional village clothes. Work on the fields would begin at dawn with mules and donkeys and end at sunset. On Sunday everything changed, as the whole village gathered at the church to pray, gossip and hold memorial services for their dead, distributing to everyone the traditional home made “kolliva” (boiled wheat with dried fruit, almonds and pomegranate seeds). Service in the Greek Orthodox Church was in the original Byzantine Greek of the bible, so I doubt whether anyone in the village, except perhaps the priest and the teacher, understood much. But it was certainly a great social occasion that I enjoyed very much. Watching how my relations who stayed behind in the village worked and how generous they were with their crops when we visited taught me a lot about family and inner well-being.

My elementary school education in Cyprus, behind the sandstone walls of the elegant Eleneion school, was badly disrupted by the independence movement against British colonial rule. During colonial rule, Greek and Turkish schools were given a lot of local autonomy. When the independence movement started in 1955, schools became the focus of some anti-colonial activity, and whenever a Greek flag was raised on the school mast, or when the army suspected something “subversive” going on, the British administration would close the school down for extended periods of time. My parents, who valued education greatly, made me take lessons from tutors outside school, and I got on. Then, when I moved on to high school, and after a brief peaceful period in a new independent state, violent clashes between the local Greek and Turkish communities broke out. This was another big disruption to my education. Of the eleven years that I spent in schools in Nicosia, only three were not disrupted by the sound of marching soldiers, exploding bombs or flying bullets. We learned to identify the location of the “troubles”, and if it was perceived to be sufficiently far, we got on with our lessons.

When I was in high school military conscription for young men started but I finished school at 17 instead of the usual 18, and I was considered too young to serve in the army. I was allowed to leave to go abroad for degree studies, with the expectation that the “problems” between the local Greeks and Turks would end before my return, and military conscription would be abolished (it is still mandatory).

Like many well-off Cypriots, I went to London to study for a degree in economics. I wanted to study architecture, but because of my father’s business my parents persuaded me to try economics or accounting. My love at school was mathematics, but it was not considered to be a good profession for a young man, with which I agreed. When I tried economics I liked it, so I decided to pursue my studies in it.

I entered a college of further education to study for my A levels (university entrance exams), speaking little English and not well prepared. It was a particularly poor college, and when I said I wanted to apply to university to study economics, I was advised to give up mathematics and study the principles of British constitution in its place. Fortunately, I had the good sense to study mathematics on my own and enter the A level exams as a private student. Needless to say, it proved to be the most useful preparation for my economics degree.

I applied to the maximum six universities that we were allowed by the central office of university admissions, but with my school background I was probably lucky to be accepted by just one of them, the University of Essex. It turned out to be a blessing, because being a campus university helped me integrate more easily into British student life, and the standard of work was very high. Like the university, the economics department was new and it was set up by young successful academics from the London School of Economics. It was a very friendly place, and it opposed separate facilities for faculty and students (a practice that I understand was given up a few years later). Richard Lipsey, Michael Parkin and Chris Archibald were particularly influential in my early studies.

In the late 1960s, when I was an undergraduate student, Essex became active in the student uprisings that characterised the times. In 1968 student political activity became particularly intense, and although I was never very active, the liberal attitudes of the time had a lasting influence on me. I remember the Vietnam war and the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King as particularly dramatic events that affected our political outlook.

Soon after, the decision whether to end my studies with the first degree and return to Cyprus, as planned, or go on to graduate school, had to be made. My teachers at Essex pressed me to go to one of the top American schools and I got an offer from Harvard. I also met Dale Mortensen around that time and he invited me to go to Northwestern to do a PhD with him. I decided to move to the London School of Economics, partly because I considered America to be “too far”, partly because my experience at Essex, which I vastly enjoyed, made me feel that I knew what to expect at LSE. Unlike Harvard, British universities were particularly bad at making up their minds about funding in timely fashion but I was fortunate to have my father’s promise that he would pay for all the costs of my education if I needed it. Eventually all my higher degree education was financed by scholarships, so I did not have to draw on that promise, but without it I couldn’t have stayed in Britain.

LSE had a completely hands-off and disorganised approach to doctoral research, leaving students alone to find a topic and write a thesis. Of course, I had a supervisor who was very helpful, Michio Morishima, whom I had met at Essex before he moved to LSE. But he was not interested in the topics that I got interested in at Essex, search theory and unemployment, which I wanted to research. He made me appreciate the classics and I read Keynes and Hicks under his guidance, but I spent most of my time reading articles and books on my own in LSE’s dusty old library rooms.

I read an enormous amount of literature, diligently taking notes, just because it happened to be there. On one occasion, and quite by chance, I stumbled on a paper by Samuel Karlin in one of the Stanford collections in mathematical economics, describing mathematical models for selling an asset when outcomes are uncertain (“Stochastic Models and Optimal Policy for Selling an Asset”, in Studies in Applied Probability and Management Science, edited by K. J. Arrow, S. Karlin and H. Scarf and published in 1962). I would take down from the shelves anything with Arrow’s name on it, because of Frank Hahn, who taught us general equilibrium theory from his book with him. “Ken Arrow strides our profession like a Colossus,” he used to tell us. Reading Karlin’s paper made me reason, let’s think of a worker’s human capital as an asset that he sells in the labour market, where job outcomes are uncertain. I tried to work on the idea and it delivered. Within six months I had a thesis in search theory that was approved for the degree of PhD. Soon after it was published as a book by Cambridge University Press, largely under the influence of Michio, who thought it was better to keep it as a single unit than break it into articles. He was himself writing only books at the time, feeling frustrated by the journal refereeing process – a feeling that I often reflected on with sympathy!

With the PhD in hand, another big decision had to be made, go back to Cyprus or apply for a university job. I had the urge to return to Cyprus but my teachers, mainly those that I got to know well at Essex, were putting a lot of pressure on me to stay in Britain, or try America. I returned to Cyprus in the autumn of 1973 to tidy up some loose ends with the thesis, intending to stay until the new year and in the meantime try life in Nicosia as a young man. The political situation at that time was getting really bad, with a military dictatorship in Greece, skirmishes between different Greek factions on the island, a Greek army that was hostile to the popular government of Archbishop Makarios, and a Turkish army to the north getting ready for action if the opportunity arose. Despite that, job opportunities started coming my way, and one of those looked particularly interesting – in the research department of the central bank. I took it, and started work in February 1974. With money that I borrowed from my father I also bought myself a plot of land covered with pine and carob trees, nestled under the cathedral rocks of Bellapais, my favourite spot on the Kyrenia mountains. I loved the combination of pine trees and views of the deep blue sea below, and I was intending to build a weekend retreat there when I made some money. With the political situation that I could see around me, it was probably not a very clever first investment!

But the urge to continue academic research was getting more intense, and I was also missing my girlfriend, whom I met at LSE but who stayed behind to complete her studies. She was from Athens and could not bear the thought of living under the dictators, so we agreed that when she finished her studies in the summer of 1974 she would move to Cyprus to live with me, get married and after a year try for academic jobs in Britain. July came and she was back in Athens with her degree, but when the time came for her to fly to Cyprus, she was too shy to fly on her own and be greeted by the extended Pissarides family at the airport. After some gentle persuasion I agreed to take a few days off work to go to Athens to fly back with her.

That decision turned out to be a pivotal event in my life. I took a flight out of Nicosia airport on Sunday night, 14 July 1974, that turned out to be one of the very last civilian flights out of that airport. At dawn on Monday, when America was preoccupied with President Nixon’s future and was not looking, the Greek army overthrew the government of Makarios, replacing it with Greek military rule. Airports closed and young men were immediately ordered to report for military service. Within days the Turkish army invaded and divided the island, causing untold misery to thousands of people. My parents escaped to the village and I lost all communication with them. Members of my family were made refugees in their own land and friends of mine went missing. The places that I loved on the north coast were lost, and my pine retreat over the blue sea had gone forever. I lost personal possessions, mostly family things of sentimental value, and even the manuscript of my book looked like it had gone up in flames at one point (although I later managed to retrieve it). My life had changed forever.

I was in Athens unable to get news of any kind other than military propaganda from the Greek colonels. Then, a few days later, news came that the dictatorship had collapsed and the exiled former Greek prime minister was returning to form a government. The whole of Athens seemed to break out into the streets in a massive party. News from Cyprus arrived that the island was destroyed by war. Even the ineffective British foreign minister, a guarantor of the peace of the island, was desperate about the situation and did not know what to do. The contrast between the celebrations in Athens and the destruction of Cyprus could not have been more stark. When I got news of my family I went with my fiancée to a resort near Athens to relax for a few hours but I ended up in the local hospital close to a breakdown. I called my teachers in Britain in desperation and Michael Parkin, whom I got to know well at Essex, found that two universities had one-year positions open, to replace faculty that took leave of absence later than usual. I borrowed a jacket and flew to England to be interviewed for them, with no money and only summer clothes for a five-day break in Athens in my bag. I was offered both jobs on the spot, and I took a one-year lectureship at the University of Southampton, teaching business economics to second year students.

Life in Southampton was tough, having to borrow both money and clothes to get by, and worrying about events back home. Teaching was boring, being in an area that I knew nothing about and was not interested in. But I threw myself into work, finishing the book on search theory and writing papers whenever I could spare a few minutes. My lectureship was renewed for a second year, but in the meantime a position had opened at LSE and I applied for it. I was offered it and I moved to London in 1976. I have not moved since.

As a young lecturer, I found LSE about as intimidating as I did when I was a PhD student. I was left alone to do my work and submit my papers, and I doubted (incorrectly, I suspect) whether many of my famous senior colleagues knew that I had made the transition and I was now their new colleague. On one occasion two or three years after I went to LSE, one of my senior colleagues called to say that he wanted to recommend me for a winter retreat in Germany organized by the Econometric Society for junior faculty. I was astonished that he knew me and I wondered, why me? Because he knew I would do well, he said.

At the retreat I was given the first chance to present to other young economists from Europe my new way of doing search – a very early version of one of the papers cited by the Economics Prize committee. They did not like it very much, saying that it assumed away too many things. I thought this was the advantage of the approach, in contrast to my PhD work, which had too many things in it, so I carried on. Unfortunately, journal referees of the early work also thought it had assumed away too many things and I had difficulty publishing my first papers. In contrast, during my brief forays into other branches of macroeconomics, like consumption theory, I found it easy to publish my papers in good journals.

During this time, the only faculty member at LSE that I remember trying to mix with junior lecturers and graduate students, and organise a research group of some kind, was Richard Layard. He talked to me about joining the informal group that he was putting together to work on applied labour economics topics, like social security, pensions and education. Although I did not consider myself to be a labour economist, and I had never taught labour economics, I agreed, and some papers were published. But my true passion was my theoretical work in unemployment theory, with which I quietly carried on in the background, without talking much to anyone about it. Still, the association with the Layard group, as it used to be known, brought several good results. It taught me to think of the empirical implications of what I was doing, something that was never impressed on me during my PhD work. It also taught me to think first of the “big problem” that we needed to understand, and then write models about it. The big problem in the late seventies and early eighties was unemployment, and that’s what I wanted to do. It also financed my first visit to the United States, a one-year Ford Foundation fellowship at Harvard, to work on the economics of education.

The visit took place in the academic year 1979–80. In the previous year, George Akerlof and Janet Yellen came to LSE and for the first time someone with more experience of the profession than I had, explained to me how to make my work better known. I was still too shy to do much about it, but at least now I knew how. They did not know my work but liked it when they saw it, and not surprisingly George advised me to focus on my unemployment work. That encouraged me and that’s what I did at Harvard, although I also wrote the two papers on education that I got the funding for.

I found Harvard a difficult place to visit. The facilities offered to visitors were basic and there was no effort to integrate visitors within the department. A few weeks after arriving, I despaired and started seriously thinking about leaving and returning to London. The lowest point coincided with the get-together party organised by the department for new and old faculty. I half-heartedly went along, and by chance I met Martin Feldstein, who asked me how I found Harvard as a visitor. When I tactfully described some of my experiences, he immediately suggested that I leave the department and I come to the NBER in Massachusetts Avenue, where I could have access to all the facilities and work in my own office. I loved it. It rescued my visit, I immediately got down to work, and I have been going back to the NBER practically every year since then. At one of their seminars I met Peter Diamond for the first time, giving a presentation of his early work on search theory. I saw the similarities with my work, but decided that I could carry on regardless, focusing, as I did, on labour markets, policy and explanations of the rise in unemployment, rather than on the more theoretical issues that preoccupied him. I think I met Peter very briefly once again several years later, but apart from these two brief meetings, I did not see him or communicated with him about our work until we both went to Stockholm for the award ceremonies.

On my return from Harvard I was deep into search and matching theory. I knew then that I was on to something good, although the work was still completely unknown outside my very small circle at LSE. This time also marked the beginning of my most productive and innovative period, which lasted for about five years. Half way through this period I went for my second long visit to the United States, six months at the Industrial Relations Section at Princeton University, under Orley Ashenfelter. I wrote my best papers during that time, even though the theoretical work that I was doing did not fit in well with the empirical focus of the Section. This period was also a very happy one (the two always seemed to go together), despite the breakdown of my marriage.

In London, Richard Layard had secured funding for a research centre in labour economics, and when the Centre for Labour Economics was created at LSE, I became one of its first members. I channelled my entire research output through the Centre and my focus on unemployment was undoubtedly reinforced by the Centre’s research objectives, which were to understand what was happening to European unemployment in the 1980s. Many distinguished economists visited the Centre and I got to speak to them, among them Bob Solow, Jacques Drèze, Edmond Malinvaud, Orley Ashenfelter, Olivier Blanchard and Rudi Dornbusch. My association with the Centre helped my work, especially in its empirical and policy implications, and it at last made LSE feel like an outward-looking, progressive place concerned with important questions. The annual meetings of the Centre were the highlight of the research year for us and equal to the best I have ever experienced. It taught me what made a successful research group: one that has people thinking along similar lines, with a common objective, and with a strong belief that the objective is important and they can make a difference. All the intellectual activity of the Centre was directed to one issue, the big question in Europe, unemployment.

But it is also fair to say that my approach to unemployment was not the preferred approach among the Centre’s members, and I did not have any papers in the Centre’s main publications, like the special issues of journals on unemployment that it sponsored. Instead, I worked on my models in a fairly isolated way and wrote my own book on unemployment, at about the same time that the Centre’s other three senior members were collaborating on the Centre’s opus magnum, Unemployment (by R. Layard, S. Nickel and R. Jackman, published by Oxford University Press in 1991). When I participated in Centre meetings, I restricted my activities to discussions about the macroeconomics of unemployment and labour market policy, some of which later featured in my work. Olivier Blanchard recently recalled my role in the early life of the Centre as a “vox clamantis in deserto,” and it reflects well what I was thinking back then.

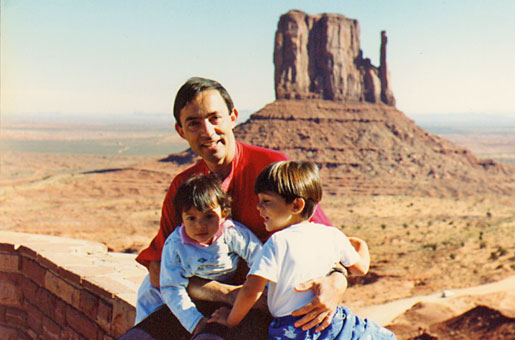

Like other British universities, LSE went through bad times in the late 1980s, as funding was cut and salaries fell behind. I got married again and had two lovely children in quick succession, Antony and Miranda. In order to support the family, I started looking for consultancy work outside, as our salaries were not enough to give a reasonable standard of living in London to a family of four. I also thought that once the children went to school, I should not go away for long, to avoid disrupting their education and their social circle. I heard horrible stories of how badly young children of British academics on leave coped with the American environment. So in 1990, when the children were too young for school, I took the young family and went to the University of California at Berkeley for the year, knowing that it was the last chance to spend a year abroad. George Akerlof was instrumental in arranging it and making us feel welcome.

The visit was enjoyable, although with the demands of the family and the attractions of California and the West, not very productive. But it did have one big highlight. During a short visit to Northwestern for a seminar I got to know Dale Mortensen better, and we started our collaboration. It lasted ten years, we became close friends, and produced our best known paper, which sealed what was already known to some as the Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides model. We met frequently, both in London and Chicago, and on one recent occasion at the Rockefeller study centre in Bellagio, Lake Como, the nearest to heaven that one can find in an academic research environment.

Back in London in the 1990s economic conditions improved, and London became a vibrant cosmopolitan centre with a European feel. Of course, most of this prosperity was driven by the financial sector, but at least for the fifteen years following the exit of Britain from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992, London prospered. We could enjoy the benefits, both in university life and in my personal life. As my book and my work with Dale were becoming better known, I thought it was time to devote more time to other activities, including spending more time with my young children. I travelled frequently to Cyprus to serve on the Interim Governing Board of its first university, which planned its statutes and made the first appointments, and I later joined the Monetary Policy Committee as an external member. I also got more involved with administration at LSE. The three years that I was head of department, from 1996 to 1999, coincided with the arrival of Tony Giddens, a progressive Director whose objectives matched those of ours in the Economics department: to make LSE the pre-eminent social sciences research centre in Europe. The time was ripe for reform and with his help I got deeply involved into modernising the department, by updating our salary structure, improving our office accommodation and helping junior faculty fund their early research and integrate into the life of the department. My early difficult experiences at LSE left a big mark on me, and I tried to make sure that things had changed for the better. The Director and Department heads that followed pushed further down the modernisation lines, establishing LSE as a stimulating place to work, equal to the best in the world.

By the time I completed my three years as head of department my collaboration with Dale gradually came to an end, and the second edition of my book was in print. It took some time to get back to serious research, slowed down by some health problems and by family pressures. I collaborated in several projects with colleagues, the main one of which was with Rachel Ngai on the employment implications of structural change. As my work became better known, and especially after winning the IZA prize in labour economics with Dale, invitations to deliver lectures abroad were coming at higher frequency. Coupled with increased funding for collaborative research in Europe and with my frequent trips to Cyprus, travel for short periods became fairly frequent and quiet research in my office more rare.

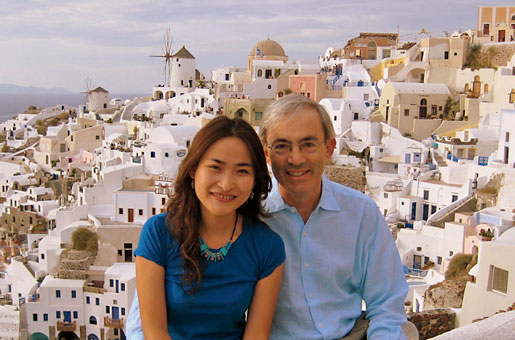

In 2008 my marriage abruptly broke down. Once the worst was over I realised that it was time to put it all behind me and turn a new leaf. Life returned to a new normal, with a new partner in Rachel and more involvement with the University of Cyprus, where I started spending more time pursuing new research interests. The affection shown to me by my colleagues and several generations of students, the family in Britain and back in Cyprus, and by both official Cyprus and its people, are moving memories that will always remain with me.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.