Interview with Paul R. Milgrom, March 2021

“Don’t waste your time with things that aren’t going to matter”

On 10 March 2021 we spoke to 2020 laureate Paul Milgrom via zoom on how his life has changed since the announcements in October, what unique item he has won at an auction and how he met his wife at a Nobel Prize banquet.

How did you find out you’d been awarded the Prize in Economic Sciences?

Paul Milgrom: Even though I knew it was the night of the prize announcement, even though people had been talking to me about it, I said, ‘I’m just going to do what I always do every night.’ I turned off my phone because that’s who I am, that’s who I’m going to be. Sure enough, this was the year that they decided to call me and I don’t have a landline anymore. I only have my cell phone. So Bob [Milgrom’s co-laureate and PhD supervisor Robert Wilson] comes by and Bob made this really hard because not only did he wake me up, he rang the doorbell and said, ‘Paul, they’re trying to call you from Stockholm. You have won the Nobel Prize.’ He doesn’t say we have won the prize. He says, you have won a Nobel Prize. I wake up and I’m a little groggy, I’m still not fully awake and I’m thinking, ‘There’s something that’s wrong with this picture.’ A call from Stockholm that went to Bob at two in the morning and he’s come to my house to tell me that I won the Nobel Prize? I didn’t know what I was supposed to think. I’m trying to figure out what’s actually happening because I don’t quite believe what he’s saying and haven’t quite put it all together yet. So that’s what happened.

The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences medal and diploma were presented to economic sciences laureates Paul R. Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson in Palo Alto.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Elena Zhukova

How has your life changed since receiving the award?

I’ve won lots of awards but nothing has the public impact like this prize. This is just completely different. But it’s also this combination of the Nobel Prize and the pandemic year. On my side, the pandemic year, it was already an unusually busy year. We’re asking the faculty just this one year to teach a little more and add some things. So I had added actually quite a lot to my schedule. I had more class teaching, teaching more hours, recording lectures. Then on top of that, once the prize came in there, thousands of extra emails and requests to give speeches and saying no, it’s really hard. There are perfectly reasonable requests, but there are too many of them. So that was one of the reasons I hired my daughter. She says no for me. And Alvin Roth [Prize in Economic Sciences 2012] gave me this ‘NO’ bell that is a great gift.

How did you meet your co-laureate Robert Wilson?

I got into graduate school at Stanford and then I wasn’t sure what to do to be a successful graduate student. I talked to a graduate student who was a year ahead of me, Bengt Holmström. He said, ‘The important thing is to get Bob Wilson to be your advisor. He’s the best advisor around here’.

So I decided I would take Bob’s class about current research and economics. Every year, he teaches a class where he goes over papers that are recently written and he went over one paper of his own and it was about auctions. I wanted to get his attention so I decided I would write my term paper to see if I could extend his work. Little did I know Bob had worked very hard on this problem. He’d been stumped and he had worked with another faculty member. I wrote a term paper, in which I solved the problem. He said, ‘This is a PhD thesis. This is it, you’re practically done.’ He was really excited and said, ‘Well, okay, it’s not quite a PhD thesis. You need to write an introduction. You need to write a literature review. Here’s all the papers you need to read better, but then you’ll be done.’ I finished very fast, two and a half years in graduate school.

You received the prize for your work on auctions – have you ever won anything on an auction?

I don’t know if you’re into sports, but one of the most famous plays in a US sports history is something called ‘the catch’, which took place on 10 January 1982. I acquired that ball at auction with auction strategy. I saw that it was for sale at auction and the auction was badly designed, but I looked at it and said, ‘That’s not a well-designed auction. I’ll bet I can get it relatively cheap.’ And I did.

Do you have a role model, mentor or teacher that has influenced you?

Bob Wilson, but there’s another man who’s another Nobel Laureate actually – Kenneth Arrow, who’s always been my intellectual hero and who was my colleague here at Stanford for many years. He had multiple laureates among his students; Eric Maskin, Roger Myerson, Leonid Hurwicz. He devoted time to educating students. I spend a lot of time working with students as well.

Is diversity important in the field of economic sciences? What is your perspective on that?

My perspective mainly is that I want people to achieve what they’re capable of. I have some really talented people that are here and it’s a disappointment to me that only some of them are soaring. That must be that I’m failing the quieter students and the women in particular. It’s not so much that I’m aiming for diversity as I’m aiming for success and training for all of my students. It turns out what I’m doing now is better for the quieter men too. It’s even better for the noisier men. It just works better.

What advice do you usually give to younger researchers?

Don’t waste your time with things that aren’t going to matter. Make sure you have a couple of things going at a time, some stuff that’s trackable that you can make progress on and some stuff that you’d really like to make progress on that you’re thinking about.

Failure’s part of it. I also tell them stories about the greatest researchers and the failures that they’ve had. I’m not going to try to repeat them. They’re more or less confidential, but the most famous people in our profession have all had times when they bang their heads against something and failed. I tell them those stories and say don’t give up.

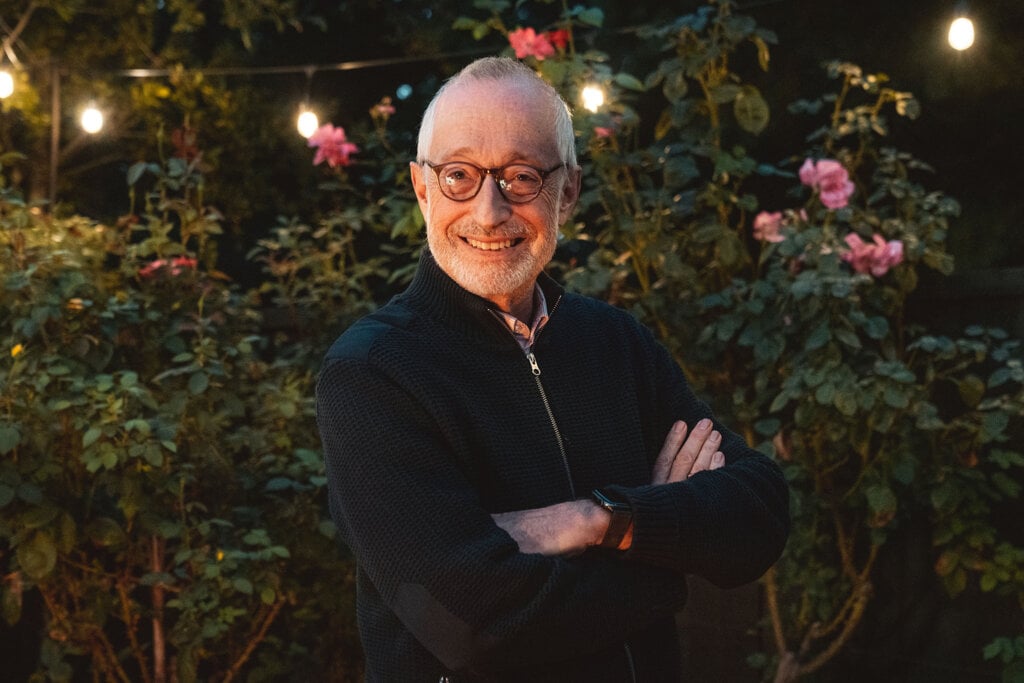

Paul R. Milgrom outside his home in Palo Alto, California, after the announcement of the 2020 Prize in Economic Sciences.

Photo credit: Andrew Brodhead/Stanford News Service

What advice do you have on dealing with failure and unexpected problems?

One of the things is that I want these guys to have portfolios and not be working on a single thing so that if they get stuck on something they could shift attention to something else. I think that it’s also dangerous. It can isolate you. That’s part of the reason for the social part of what I do. I think that people can become isolated and depressed and then they can go hide. I have to prevent that from happening. I’d like people to have in mind that there are lots of things they could be working on and they’re working on something right now, if it fails, there’s something else they can move to and get support and collaborate.

I was an assistant professor at Northwestern University. We had a group of people that included Roger Myerson, Bengt Holmström, Dale Mortensen who all are laureates. A group of young people, all of whom just thrived. We were not people who were getting offers from all the best places so how did this happen? I think that it’s partly social. It was a corridor we all worked in and we had lunch together every day in a coffee room. You could go in and see one guy explaining work to somebody else. We made comments on one another’s work, which were helpful. And yet we also competed. I would go out there and see Myerson and Holmström doing the work and say, ‘Holy cow, that’s awfully good. I’ve got to make my work better’. You’re comparing yourself to the others in a group but you also provide support. I’m trying to create a similar structure for my graduate students. One that support them in the way that I think I was supported in.

How do you like to spend your free time?

There’s something called free time? I don’t have a lot of free time, but I love spending time with family. When I was healthy (I had a knee replacement last year) I used to ski and I’m looking forward to skiing here again. I used to play tennis. We go hiking, we go for bike rides. I hang out with family, nice dinners.

I read some fiction, some nonfiction. I haven’t had much free time in the last months actually. So I haven’t done a lot of reading, but hope to get back to that. I have some books that I loved reading but then I get onto the next one. It’s like in my research to write the thing that I’m most excited about is usually something recent. That’s how I am, I move on.

You’ve been to four Nobel Prize banquets and I heard that you met your wife at one of them. Can you tell us about that?

I was there because William Vickrey, who won the prize along with James Mirrlees in 96, had a heart attack and died and they needed somebody to give the prize lecture. I was invited to give a portion of that lecture. They seated Eva next to me during the dinner. We had a really good time during the dinner. I really liked her. I thought she liked me. We danced and we had a good time. I could tell you more stories about the dinner, but I got home and I thought, ‘Well, am I going to do anything about this? She lives in Stockholm. I live in California. I’m going to reach out to her and she’s going to talk to her girlfriends and they’re all going to say he lives in California. That can’t work.’ I am a game theorist so I decided I needed to make a move that would counter that. So I sent her a really nice letter. I told her how much I enjoyed our evening and that I really wanted to see her again. Given that she lived in Stockholm and I lived in California, I would send her a plane ticket to meet her anywhere in the world. We got married around 20 years ago.

Ten years later, we were invited back by the Nobel Foundation to celebrate our 10th meeting anniversary and to give a press interview. I have to tell you this story too, because I delivered the best one-liner of my life in this interview. During an interview they asked me, ‘How do you feel about the fact that it wasn’t you who won the Nobel Prize?’ I replied, ‘Oh, I’m the one who went home with the big prize back here.’ It’s the best line of my life because people were talking about that line for the whole next year. I wish I could come up with a line that good again, but it just came right out of me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.