“It’s more fun to work with your friends”

Interview with Joshua Angrist, March 2022

Nobelprize.org interviewed economic sciences laureate Joshua Angrist on 21 March 2022. He told us about his aversion to studying as a youth, thoughts on teaching and friendship with co-laureate Guido Imbens.

Can you tell us a little bit about your childhood?

Joshua Angrist: I was born in Columbus, Ohio and I grew up in Pittsburgh. We moved to Pittsburgh when I was three. My parents were academics. They got their PhDs from Ohio State and my dad had also been stationed in the air force and an air force base near Columbus, Ohio, where I was born. My parents got their first jobs in Pittsburgh, so we moved to there and eventually they both left academia, but they never left Pittsburgh. That’s where I grew up, went to elementary school, middle school, high school.

We understand you weren’t particularly academic as a youth?

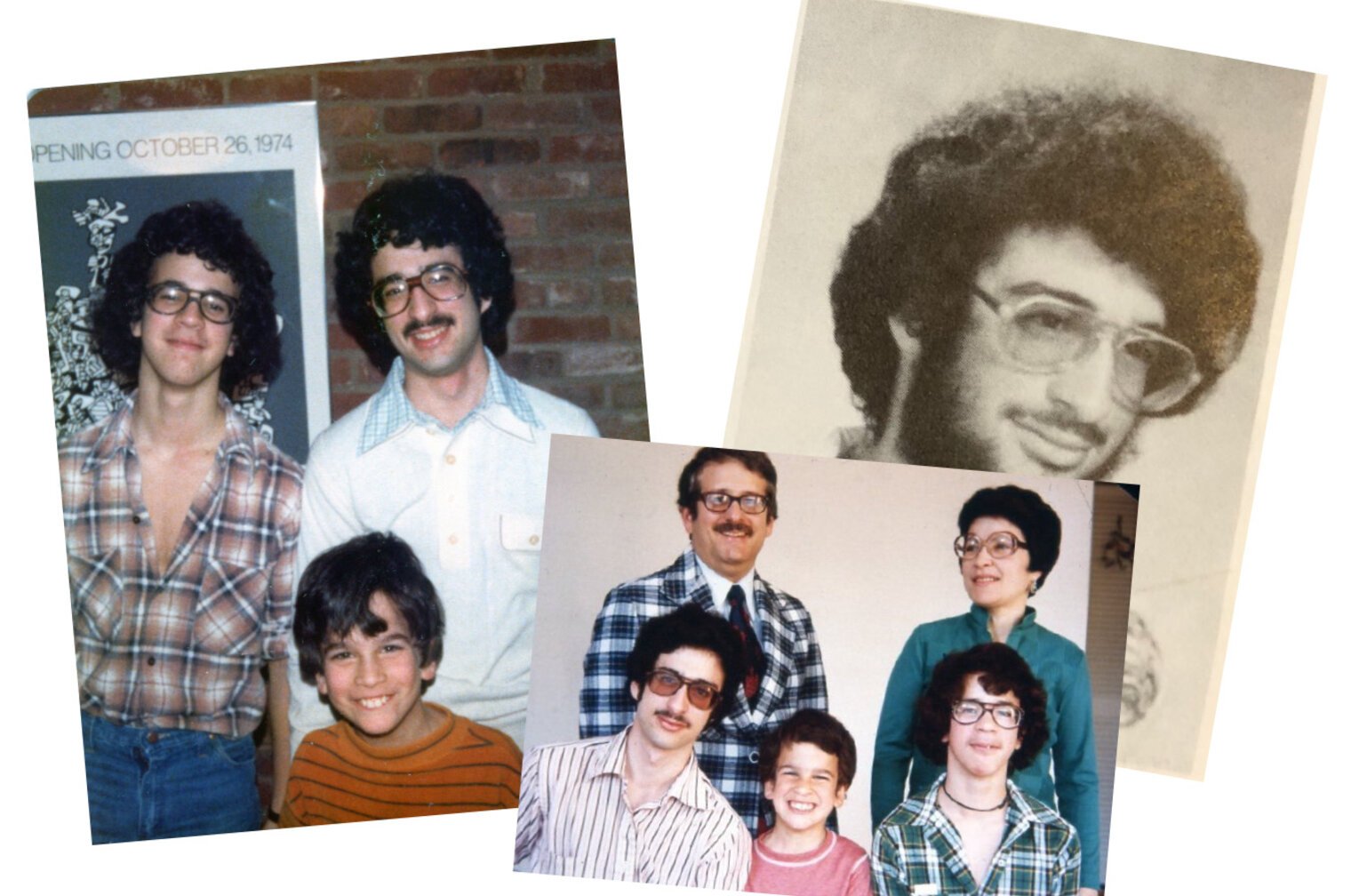

A collection of photos of Angrist in high school. L-R: Angrist with his younger brothers, Misha and Ezra; the brothers with their parents in Pittsburgh; Angrist’s high school yearbook picture.

Photo courtesy Joshua Angrist

Yeah, I wasn’t a very good student and actually my parents didn’t like being professors very much so they both quit that. So maybe it’s a little ironic that I ended up being a professor. I got in some trouble for various reasons in school and I didn’t really get engaged with high school at all. After maybe ninth grade, I didn’t take any of the accelerated college courses and I just wanted to finish as quickly as possible. So I managed to finish high school in 11th grade by meeting all the state requirements for diploma. I took two English classes, two health classes – that was sex education, badly done – and, two gym classes, physical education classes. And I was able to get my diploma and leave high school. I worked for a little bit more than a year and then I decided probably I should go to college.

Why were you so keen to leave school and start working?

Well, I hadn’t found anything that interested me in school. There were things that interested me. I had a lot of hobbies. I had a photographic dark room – this was before digital photography – in my basement where I developed my own film. I enjoyed print shop in high school and we made t-shirts out of rock albums covers and that sort of thing. I had various other hobbies but nothing in school really engaged me. I liked working partly because I thought working was fun, but partly also I wanted to have money. Once I was 16 I bought my neighbour’s car. So I had this awesome powerful car, but it was high maintenance and had terrible gas mileage. It got six miles to the gallon, so I always needed money to pay for gas, repairs, and insurance. I had started working anyway – I had my first job when I was 13, I think I worked in a restaurant as a bus boy. Then later I got interested in working with people with mental disabilities and I worked at camps. So that’s what I went to do.

So where does your passion for economic sciences come from? Was there a particular person that influenced you?

I think, like many people, I got excited about my field through an inspired and inspiring teacher. When I arrived at Oberlin College in Ohio, I didn’t know what I wanted to study. I thought maybe I would continue in the special education field so I took psychology. But already in my household we talked about economics, my father in particular was interested in economics, even though he was an engineer. I had some sort of dinner table background so I took Econ 101 and I really liked that a lot. I had a wonderful teacher named Bob Piron and I thought his class was so much fun. I liked the material. I also liked the way he taught. It was sort of a high-pressure classroom. Later I adopted that style. I think that’s going out of style now, but it was lots of cold calling and a very challenging dynamic classroom atmosphere. It wasn’t relaxing, but he was also a very funny guy. I enjoyed it a lot and I connected with the material I saw. I had some affinity for it. It wasn’t that it was easy, but I was willing to spend the time on it. So I took a lot of economics and I liked almost all of it.

You yourself say that you weren’t a good student but a lot of your research is around education. Can you tell us a little about that?

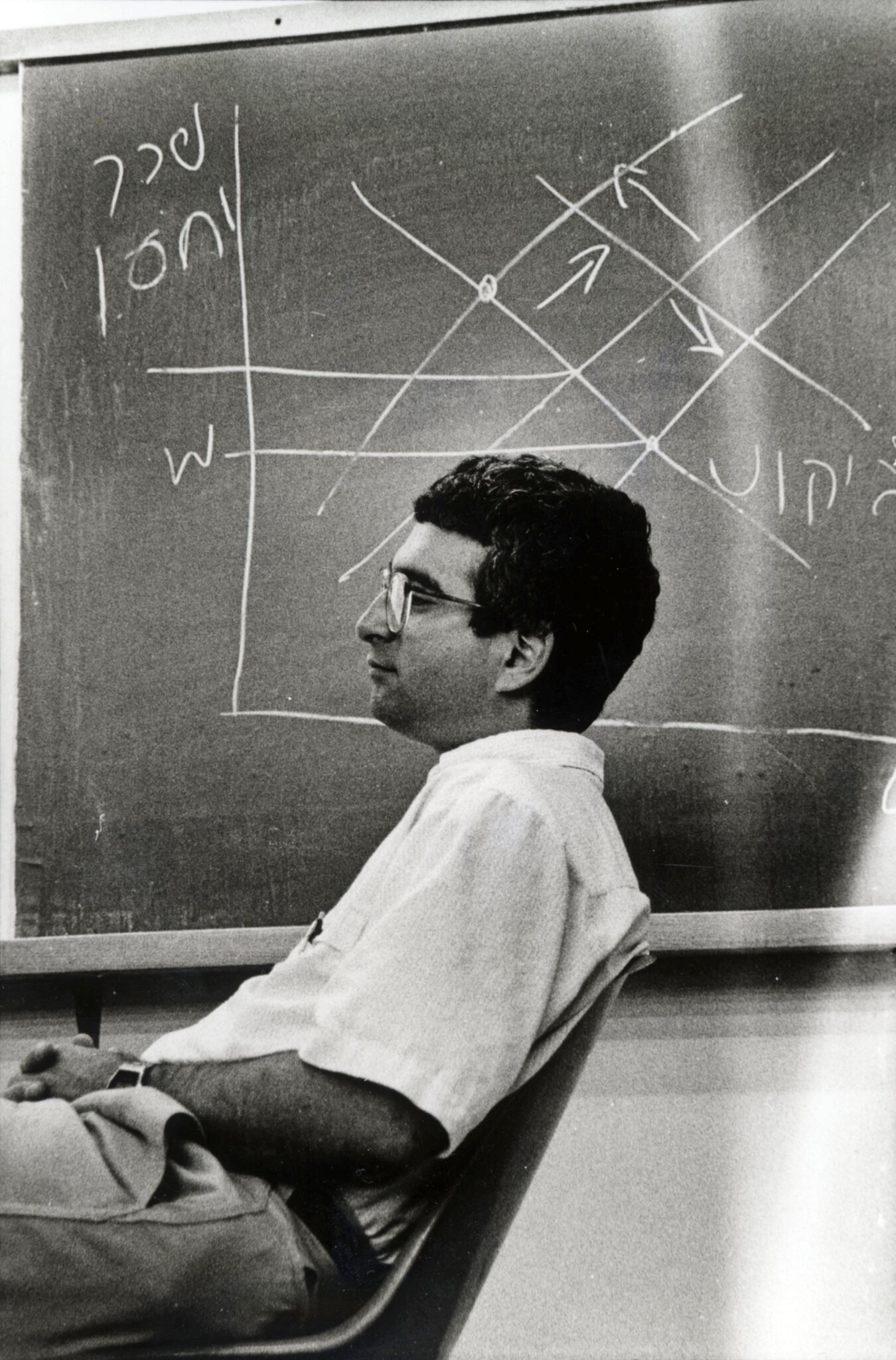

Joshua Angrist at Hebrew University in the 1990s.

Photo courtesy Joshua Angrist

It is sort of inconsistent with my personal history that a lot of my scholarship shows that education is very important. It’s an important determinant of people’s earnings. I didn’t think so, but then I was a teenager. That’s one thing. And anyway, I’m only one data point. One thing I teach my students is try not to learn from your personal experience. Your personal experience might be idiosyncratic and not really informative. Everybody, for example, has a view about schools and what schools are good. I try not to pass judgment on that until I see the data. Another thing to keep in mind is that, even though I wasn’t a great student and I grew up in a fairly modest household, it was a very educated household. So I had a lot of advantages and I had the opportunity to goof off in high school and learn nothing and yet recover. I think a lot of people, particularly people whose parents aren’t very educated, they’re not going to get that second chance.

Your prize in economic sciences lecture was very engaging. How important is it to communicate about your work?

It’s very important. I like doing research, but I also love teaching and a good teacher is an evangelist for their field. Particularly when you’re teaching undergraduates, you have the opportunity to change somebody’s direction by convincing them or showing them that economics is really fascinating and rewarding. I think about my own experience in this case, even though I don’t want to learn too much from it, as I said, but I had charismatic teachers and they affected my direction and I think maybe I can have that effect on my students. That’s what I aspire to.

What qualities do you think you need to become a successful research scientist or economist?

If you want to be a successful research scientist, you have to really love what you’re doing. You have to find it interesting. You can’t just be going through the motions. When people come to talk to me about graduate school, I caution them that it shouldn’t be a momentum play – meaning that you’ve been a good student all your life, you’re bright, you did well in college and so you figure you should be go to graduate school. I think that’s not a very good scenario for success because graduate school is really not more of the same. There’s a different quality to it. You have to be very self-motivated and you have to be able to set your own goals and push yourself to meet them. Nobody’s waking you up in the morning and saying this is what the team has to do today. There are moments like that, but it’s mostly not like that. And so if you don’t love it, you’re not going to get it done.

That would be the first thing. And then you have to have some affinity for it. You have to have the right skills, the right mindset within economics. I suspect within other fields there’s more theoretical and more empirical type of people. Even the prize I share, there’s two parts. One is for David Card and his empirical work. He was actually one of my thesis advisors. I share [the other half] with Guido Imbens for methodological work, but I’m an empiricist at heart.

You are good friends with your co-laureate Guido Imbens, and were even best man at his wedding. Can you tell us a little about your friendship?

Economic sciences laureates Guido Imbens and Joshua Angrist in Washington DC on 6 December 2021.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Risdon Photography

We’ve been friends since our academic childhood. I got my PhD in 1989, and I went to Harvard for my first job. I was only there for two years, but luckily Guido came in my second year and we were also neighbours. And, you know, I wasn’t very excited when we hired him. I thought his thesis was kind of boring. It was very dry and technical, but we soon hit it off and became friends and we saw a lot of each other. We started talking about these kind of applied problems that I was interested in, like using the draft lottery to estimate the effects of military service, and then some subsequent work I had done with Alan Krueger using season of birth to estimate the economic returns of schooling and Guido and I started saying, well, what could we say formally about what you’re actually learning when you do that?

It must have been very special to get the prize alongside him, given that he’s such a good friend.

Yeah it’s fantastic. We couldn’t be happier.

Do you think friendship’s important in work and collaboration?

It can be, but it’s not essential. I think it’s more fun to work with your friends. I tell my students that you want to pick your collaborators as carefully and thoughtfully as you pick your spouse. If it goes badly it can be very painful and hard to unwind. Certainly, when you’re friends with the people you work with, you worry less about that. Academia is very competitive and the stakes are seen as very high for the participants. Society maybe doesn’t care too much who wrote which paper or who gets credit for which idea, but we care. That can be a source of great tension. So you need to trust your collaborators and you trust your friends. Not everybody I’ve worked with is a close friend. I don’t think that’s essential, but it’s definitely more fun.

Talking about advice to students, is there one piece of advice that you would give to a young person interested in research?

I talk to a lot of people who want to have careers in research, and I try to give them a clear picture of the life of a scholar. Some of it’s fun, a lot of it’s a drag – every job has its good parts and bad parts. We serve on committees and sometimes we disagree within the department and those can be unpleasant situations, a little bit like a family quarrel that can be very tiring. So you have to be very motivated. You really have to believe that if you want to have a career in research. I always say, who’s your role model? What’s the scholar you want to be, what sort of work you want to do, tell me some paper you wish you’d written. I try to get them to think about it very concretely, not as an abstract. And if they’re excited about that career, I think that bodes well.

It sounds like you are very passionate about your research – what do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I like my work a lot and I’m sort of obsessed by it, so I never stop thinking about it, but I do have some hobbies still. I’m a cyclist. I ride every weekend. Sometimes I go mountain biking or road biking. That’s my main hobby. I ski a little in the winter and now I have a new hobby, which is even more rewarding – that’s grandchildren. My family is very important to me and the highlight of the week is definitely seeing the grandchildren.

Joshua Angrist out with one of his grandchildren.

Photo courtesy Joshua Angrist

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.