Joshua D. Angrist

Interview

Interview, March 2022

Joshua D. Angrist

Photo courtesy of the MIT Department of Economics

Nobelprize.org interviewed Joshua Angrist on 21 March 2022. He told us about his aversion to studying as a youth, thoughts on teaching and friendship with co-laureate Guido Imbens.

Telephone interview, October 2021

“My lack of preparation is evidence that I didn’t expect it!”

Telephone interview with Joshua D. Angrist following the announcement of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2021 on 11 October 2021. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Chief Scientific Officer of Nobel Prize Outreach.

“I saw that my phone was flooded with text messages,” says Joshua Angrist, having slept through the calls from Stockholm. In this brief interview he describes how he therefore called the MIT Press Department to check, and discovered it was true! The conversation turns to his work on the assumed benefits of elite schooling, his working relationship with his co-laureates and what lies behind his productive collaboration with Guido Imbens.

Interview transcript

Angrist: Hello?

Adam Smith: Oh hello, am I speaking with Joshua Angrist?

JA: Yes, speaking.

AS: Hello, this is Adam Smith from Nobelprize.org

JA: Hey Adam.

AS: Hi.

JA: Great name, great name.

AS: [Laughs] Many, many congratulations.

JA: I’m sure you’ve heard that before. Yes.

AS: Yes, I hear it particularly on this day of the Nobels.

JA: [Laughs]

AS: Many, many congratulations.

JA: Thank you, thank you, I’m honoured, I’m thrilled.

AS: How did you actually discover that you had been awarded the prize in economic sciences?

JA: I woke up early in the morning for no particular good reason and I saw that my phone was flooded with text messages, and I had had it off because I was not expecting anything special this morning, so I had to look at the phone. And then I tried to find the phone number that I should call to figure out if it was true.

AS: So you came through to Stockholm, to the Nobel Foundation offices.

JA: Actually I called someone at MIT who had called me.

AS: You spoke to someone who confirmed it?

JA: Yes, our press office.

AS: Right, great. Given that you’re in the business of collecting evidence for causal relationships, yeah, you wanted to be certain.

JA: Yes, I wanted to be sure … I didn’t really expect it, I suppose everybody says that, and you’re supposed to say that. But I think in my case my lack of preparation is evidence that I didn’t expect it.

AS: How does it feel to have received it?

JA: It’s wonderful, it’s overwhelming. It’s you know, it’s the beginning of the day here in the United States, and I’m trying to absorb it. I am especially happy to be grouped with Dave Card and Guido Imbens, who are certainly worthy, and, you know, I’m lucky to have been able to work with them and learn from them.

AS: Because you were David Card’s student for a while weren’t you?

JA: Yes, I was one of his graduate students. I had three wonderful advisors, but he surely had a huge influence on me and my development as an empiricist. Then Guido Imbens was one of my first collaborators, and we embarked on a path of methodological work that proved to be very rewarding to us and, and influential.

AS: What was it about that relationship in the early 90s that kind of spawned those papers. What was special about the combination of the two of you?

JA: We enjoyed working together, and we found that we were interested in the same kind of problems. We were both assistant professors at Harvard. I had been there for one year. Guido came in the second year, and then I left after that actually. I moved back to Israel where I taught for five years, and at Hebrew University. But Guido and I kept collaborating and we, we had started on something that we thought was interesting and important. I guess we didn’t really know quite how important, and we set out to kind of figure out what instrumental variables, which is the statistical technique that Guido and I have studied together most closely. What we really learnt from that is, it was based in part of my applications, and it developed with his theoretical insights, and we kind of went back and forth between, you know, applied questions and methodological questions, and came up with a whole framework. People today call it the LATE framework. In the beginning it was one paper, and then that paper didn’t get published, and then it was the second paper that did get published, and then it developed further.

AS: Your work is all about finding the basis for people’s beliefs, if you like. So can you give me an example of, for instance, in education, something that is a popularly-held belief that actually is not supported by evidence, that you’ve found?

JA: That’s an interesting question Adam. I don’t know if my work is about people’s beliefs, but it’s about, you know, people can believe what they want to believe. But it is about discovering what is true in the sense of ‘is there a causal effect of something?’ In other words, if you did a particular thing, maybe related to education, what would happen to you. [Phone beeps] My phone is going off here. A great question of that is something that many people believe, for example, that highly-selective public high schools, or highly-selective universities are the key to a successful career, especially in my world where we work in such institutions on the university end. And what I’ve been able to show using some of the techniques developed in work with Guido and in, in the training that I had with Dave Card, is that that’s often illusory. It reflects a phenomenon we call selection bias, that people who go to those schools tend to do well in life, but they were going to do well in life anyway, that’s how they got into the schools. So that’s a great example of selection bias. And the techniques that all three of us have worked on are about reducing or mitigating selection bias in empirical estimates, and using mostly observed data to get at the kind of evidence that we would like to have, say, from a randomised trial.

AS: I would like to talk much more about this, but your phone buzzing is going to be the story of the day really, isn’t it?

JA: [Laughs] Yes.

AS: What would be very nice is if we could have a longer conversation when things quiet down a bit for you, although I think it will be quite a little time before things do quiet down.

JA: Yes, probably.

AS: I don’t know, I don’t know, you sound pretty, you sound pretty together and calm at the moment.

JA: I like to talk about my work, so that always calms me down.

AS: I think I hear a coffee cup rattling there as well, maybe.

JA: Yes, I have a little coffee here.

AS: That’s an important constituent of the day I think. I shall let you get on with your day. Good luck with it – it was a pleasure to speak to you, congratulations.

JA: Thank you so much Adam. Great speaking to you.

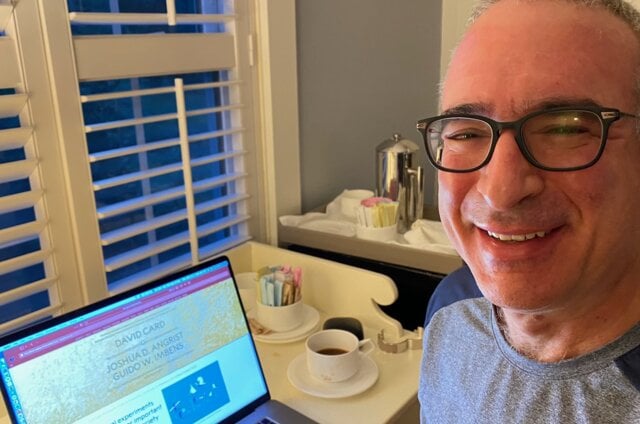

Joshua D. Angrist on the day of the announcement of the prize in economic sciences, 11 October 2021.

Selfie by Joshua Angrist.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.