Guido W. Imbens

Biographical

Introduction

In this biographical sketch I will discuss part of my personal and academic journey, how I originally got interested in econometrics, and how I continued in this area as it changed from a field where causal inference was almost non-existent to one where causality is now explicitly a major part. During the same time that causal inference became a major part of econometrics, it also flourished in other disciplines with statisticians, political scientists, psychologists, epidemiologists, and computer scientists all bringing new questions and methodological perspectives to the table. The applications range widely from biomedical to social science ones, generating interest among researchers and policy makers in academics, government as well as private sector organizations. I see this prize therefore partly as a recognition of the importance of this general interdisciplinary enterprise and hope it serves to further invigorate the field.

My Early Years

I grew up in the Netherlands. I was born in Geldrop, a small town outside Eindhoven, on September 3rd, 1963. I have one brother who is a year and a half older than me, and a sister who is three years younger.

I do not remember much from the six years I spent in Geldrop. When I started primary school, we moved to the nearby town of Eindhoven. My father worked at the Philips electronics company whose headquarters were in Eindhoven and which at that time was the biggest employer in the Netherlands. Eindhoven was essentially a company town with the local professional football club, as well as most of the cultural institutions and parks funded and often named after the founders of the Philips company and some of their relatives. My father had studied physics in college for one year before taking a position at Philips for financial reasons. He spent his entire career at Philips, initially on the engineering side, and later in the marketing and sales of oscilloscopes and other equipment. My mother had also worked at Philips before they got married. Both my parents later went back to college, my mother when my siblings and I were in high school, and my father after he retired from Philips. I went to a Catholic primary school in Eindhoven. Both my siblings and I excelled in school. It all came relatively easy to us, and we enjoyed having our father give us mathematics problems in the evening. Typically, these involved long sequential calculations that − close to the end − included multiplication by zero to make them easier to check for him. At times we were bored in school with the curriculum, and I recall a year when my brother and I would work through a mathematics book early in the morning before school, simply because we enjoyed doing so. There was little pressure from our parents to study hard, or any sense that we were unusually good academically.

When we were living in Eindhoven my mother also got involved in local politics. Initially she focused on persuading the municipal authorities to provide more playgrounds for the children in our neighborhood. She organized and successfully led a group of parents to lobby the authorities. She was a remarkable and strong-willed person with firm principles, and not easily dissuaded by peer pressure or fear of being different. Once a year the housing corporation would come and paint all the front doors of the rental houses, all owned by Philips, mustard yellow. Every year the following day my mother would paint our front door black, much to the embarrassment of my siblings and myself at the time. Later she became involved in groups agitating for change in the Catholic Church. At the time the custom in the weekly religious services in the church was to collect money from the parishioners twice. Once for charity, and once for operating expenses for the local parish and the diocese. Out of unhappiness with church policies she would donate liberally for the charities but refused to donate any amount for the parish and diocese, often leading to a silent standoff with the person attempting to collect the money. Again, at the time this was a source of great embarrassment for us, but now I see that many of the character traits that made me successful in my scholarly endeavors, including stubbornness, came from her. My father was more easy-going. His outside interests include gardening. He had a vegetable plot, in Eindhoven, and later in Deurne, that he rented from a local organization, and would grow a lot of our vegetables there, long before organic gardening became fashionable.

After six years in Eindhoven we moved to Deurne, a small town about 20 miles east of Eindhoven. My father continued working for Philips in Eindhoven and would commute by train. In Deurne I started high school at Peelland College Deurne. Within the Dutch educational system this was an academic-track high school. It was led by a visionary principal, Theo Hoogbergen, who expanded the school substantially and made it a great fit for me with many committed teachers and extracurricular programs. The choice had been between Peelland College and the more old-fashioned Gymnasium next door, which was run by a religious order. The decision was an easy one when we visited Peelland College, and Hoogbergen himself helped us fix the tailpipe on our car which broke down when we were about to leave.

Early on in high school my favorite subjects were mathematics and Latin. I enjoyed translating poems by Marcellus and reading parts of Caesar’s De Bello Gallico. In the 4th (out of 6) year of high school I started taking an economics class. I was not particularly taken with the subject. Moreover, I had a dispute with the economics teacher that led to me being banished from the class for about three weeks. The dispute involved the solutions manual for the textbook we were using, and which out of principle I refused to turn in on the grounds that I had paid for it. The dispute got resolved when the principal caught me wandering the hallways, and I went back to class. During my high school years, we had school trips to Prague (still behind the Iron Curtain at the time) and Rome, both making a great impression on me, and making me more curious about exploring the wider world.

Towards the end of my high school years in the Netherlands I had to decide what college major to apply for. In the educational system in the Netherlands, students apply for a specific major, rather than to a particular university. Once at the university it is possible, but not completely straightforward, to change majors. This does lead to some inefficiencies in the educational system, because potential students often have little sense what a particular major will actually involve. At that time, I enjoyed mathematics, and both my siblings ended up studying mathematics in college, but I wanted to do something more applied, with more direct relevance for society. My economics teacher, with whom I was at that time on better terms after the initial banishment from class, introduced me to a small book by Jan Tinbergen, the co-winner, with Ragnar Frisch, of the first Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel in 1969 [Tinbergen, 1941]. Tinbergen was an inspiring figure in the Netherlands. Beyond his scholarly achievements, he had been a tireless institution builder. He founded the Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, which became an authoritative non-partisan voice in Dutch policy circles, and later worked for the League of Nations and the United Nations. Curiously he not only won the Prize in Economics, but was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In addition, his brother Niko Tinbergen was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Tinbergen also established econometrics as an academic discipline in the Netherlands, separate from economics. This was partly out of unhappiness with the economics program at the time. This was a bigger accomplishment than it may seem, because in the Netherlands establishing a new academic discipline requires formal government approval. In this program the term “econometrics” was used in a broader sense than it is used nowadays, and more in the spirit of the way it was interpreted by the founders of the Econometric Society in 1930: it included mathematical economics and operations research. The book I read, and more generally Tinbergen’s story [Dekker, 2021], inspired me to enroll at age seventeen in the econometrics program at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, where Tinbergen had spent most of his academic career. I have continued to study econometrics ever since.

My Undergraduate Years

The econometrics program in Rotterdam was a fabulous program. Beyond Tinbergen the program had been heavily influenced by Henri Theil, who led the program for many years and who made it into an internationally renowned research environment [Kloek, 2001]. The program was very small. There were about sixty first year students in the program the year I started (compared to over 1,000 in the regular economics program), and by the end of the year there were about twenty-five left. That was the result of the program being quite challenging. It had that reputation in general, and so all the students who entered the program were quite strong, but still, many found it hard to keep up with the workload and switched to the general economics program, which was much easier. Because the program was so small, we had a lot of direct interaction with the faculty. The faculty took great pride in the program and its illustrious history.

The faculty did make us work hard. We started in the first year with the microeconomics course that was also intended for second year students in the economics program. I particularly recall an operations research course by Alexander Rinnooy Kan. He had just spent a year in the US at MIT and Berkeley, and exuded brilliance. It was the first time that I actually started questioning whether I was smart enough to stick with the program, and it forced me to work harder than I had ever done before. The main drawback of the program was that it was largely focused on technical material. This made it extremely good preparation for a PhD program in the United States, but it left us somewhat unprepared for discussions of real-world economic problems. I remember preparing for an exam in macroeconomics after we had studied theoretical models for economies that included markets for goods, money and bonds. At the end of the semester, when studying for the exam I realized I did not actually know what “bonds” were, even though we had discussed models with bonds for much of the semester. To my surprise none of my classmates had any idea what bonds were either, suggesting that while we might have been comfortable with the technical part of the material, we were not so clear on the substance!

By the end of my second year, I was more comfortable with the demands of the program. I registered for a double major (the second being social history) and started working as a research assistant in the international economics group for Jean-Marie Viaene and Caspar de Vries. Both had done their PhD in the US, and made that sound like an exciting possibility, even if a somewhat remote one.

During my third year I also made another small, but consequential decision. Marcus Berliant visited from the University of Rochester and offered a course in mathematical economics. Specifically, the course was on general equilibrium with infinitely many goods. We had not even done general equilibrium with a finite number of goods in the Arrow–Debreu sense, so it was not clear why this was a good course to take, but I was curious and registered for the course. Marcus taught the course incredibly well, with problem sets every class that really forced me to engage deeply with the material. The mathematical level of the course put most of the students off, though, and after the third class I was the only student left, with a couple of faculty attending, presumably out of politeness more than anything else. This caught Marcus’ attention, and he encouraged me to think about doing a PhD in the United States. This was not just cheap talk on his part: when I applied later for a PhD at Rochester he managed to get me an offer of a full scholarship.

England

Towards the end of my third year, I had applied on a lark for an exchange program to spend a year at the University of Hull in Kingston upon Hull in the north of England. Together with a fellow econometrics student, Wilbert van der Klaauw, now at the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, I went to Hull, initially for the academic year 1984-1985. At the University of Hull, we both enrolled in the master’s program in economics. The head of the department, and senior econometrician, Anthony (Tony) Lancaster, was very surprised and pleased to suddenly have two well-prepared econometrics students in his class. Tony was working on duration models at that time. He had finished an influential paper on that a few years earlier [Lancaster, 1979], and during my time in Hull he was finishing a monograph on duration models [Lancaster, 1990]. He taught us from drafts of various chapters and had us do empirical exercises in this area. Tony’s teaching style involved a lot of silences. A student would ask him a question, and rather than answering, he would let the question hang in the air, while he pondered it. These silences were even more emphatic because he would get out his snuff box and snort some, while he and we were pondering the question. Sometimes he would respond with a different question, often one that at first did not appear to be connected to the question that had prompted it. But eventually we would figure out the connection and get to the answer. It was a very effective way of forcing us to engage deeply with the material.

By the end of that year, I had obtained a master’s degree. There was now little point in going back to finish an undergraduate degree in Rotterdam. Moreover, Lancaster was negotiating a move to Brown University and he asked Wilbert and myself if we were interested in staying another year in Hull as research assistants and then doing a PhD at Brown. We both gratefully accepted and moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in the United States. Both of us ended up staying in the United States, with Wilbert van der Klaauw moving from New York University to the University of North Carolina and eventually to the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

Graduate School at Brown University

The PhD program at Brown University suited me well. It exposed me to much more economics as opposed to econometrics than I had seen in Rotterdam and Hull. In particular the macroeconomics courses by Peter Garber and Herschel Grossman made much more sense to me than the earlier courses I had taken. Because I had taken most of the econometrics classes Brown had to offer, I took some classes in the applied mathematics department on Bayesian statistics. The workload was much higher than it had been in Hull, and during my second year I started questioning whether I really wanted to continue in the program. I even applied for some jobs outside of academics. When I read about a position at a bank in New York that required a master’s degree in economics, as well as fluency in Dutch, I was sure I would be a shoo-in for the job. However, I did not even make it to the interview stage, and ultimately decided to buckle down and continue in the program.

I also enrolled through an exchange program in some courses at Harvard University, including one with Gary Chamberlain that made a big impression on me. In my fourth year of the PhD program Brown, I moved back to Holland to take a position at Tilburg University, not quite sure whether I wanted to spend the next phase of my career in the US or Holland. Arie Kapteyn, dean at the University there, had met me at a conference, and always looking to expand his econometrics group, invited me back. I did go on the US job market though. With considerable good fortune I got an offer from Harvard University and that settled the question of Holland or the US. Harvard had not actually interviewed me at the annual meetings, but after other candidates had not impressed them, and faced with the prospect of not having enough faculty to teach some of the required econometrics courses, Gary Chamberlain interviewed me over the telephone and then invited me for a formal job talk. Although Josh Angrist, who later became a very good friend, apparently was not impressed, Gary was, and I got the offer.

Life as Junior Faculty

I moved into Harvard faculty housing on Walker Street in Cambridge, walking distance to the university, and in fact next door to Eric Maskin (winner of the Prize in Economics in 2007). The Harvard economics department was an exciting but also an intimidating place as a junior faculty at the time. The econometrics seminar run jointly with the economics department at MIT had a remarkably large number of senior faculty attending. This included Zvi Griliches and Dale Jorgenson from Harvard and Dan McFadden and Jerry Hausman from MIT, all winners of the Clark Medal, given biannually for the most influential economist under 40, and traditionally a strong predictor of the Prize in Economics. It also included the more recently tenured Gary Chamberlain and Whitney Newey as well as some junior faculty, including Jeffrey Wooldridge and Danny Quah on the MIT side and Josh Angrist and myself on the Harvard side. The four senior people, Zvi Griliches, Dale Jorgenson, Dan McFadden, and Jerry Hausman, had been at the forefront of econometrics for many years and had strong views on what was good research in econometrics, forcing speakers at the seminar to defend their ideas and hone their arguments.

Josh Angrist, although originally not a big fan of hiring me, was a great junior colleague. We had many discussions over coffee in the nearby Science Center, as well as long sessions in the local laundromat where we would do our laundry on Saturday mornings. He introduced me to many of the debates in labor economics he had been exposed to at Princeton in the Industrial Relations Section with his advisors Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, and his collaborator Alan Krueger, and which had not made it to Brown University yet when I was a graduate student there. These discussions had a great impact on my thinking, as did conversations with Gary Chamberlain which focused more on the theoretical econometrics side. It was the combination of the two perspectives that would prove to be the lasting influence of my junior faculty years at Harvard.

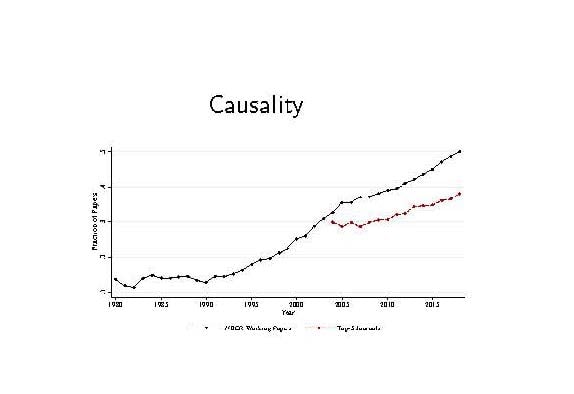

Causality was not a term that was widely used in econometrics in the 1980s when I studied in Rotterdam, Hull, or Brown University. There was Granger–Sims causality, a concept used in time-series analysis. This measured, in various forms, whether one time series could or could not predict a second time series, conditional on the past. In micro-econometrics or empirical micro, however, it was not a term that was regularly used in papers or seminar presentations. This figure, based on similar figures in a paper by Janet Currie, Henrik Kleven and Esmée Zwiers (Currie et al. [2020]) illustrates this. It shows that among empirical micro papers in the NBER working paper series, about 5% used the term causal or causality at that time. This was not just in empirical papers. Looking back at the syllabus for a graduate econometrics course I taught at Harvard in 1991, there was no mention of causality either. It was not even that we taught the students the common adage that “correlation is not the same as causality.” The term was simply not used. In the econometrics courses I taught in my early years at Harvard it would not come up, and even experimental design was not part of the curriculum. This avoidance of the term had a long history. Although Tinbergen used the term explicitly in his work including [Tinbergen, 1940], later there was explicit advice against the term. As late as 2001, McFadden wrote in his 2001 Prize lecture that “detection of true causal structures is beyond the reach of statistics” and recommends that “For these reasons, it is best to avoid the language of causality” (p. 369, McFadden [2001]), despite the fact that the questions he analyzes regarding the demand for public transportation under different regimes are clearly causal.

In the 1990s that began to change, although slowly. Papers started to use the terms explicitly. Josh and I did not actually use the terms causal or causality in our 1994 paper [Imbens and Angrist, 1994], but two years later in the 1996 paper with Don Rubin [Angrist et al., 1996] there are already 123 instances of the “causal” or its derivatives. In 1995 when Don Rubin started what was, as far as I know, the first graduate course entirely devoted to causal inference, the registrar’s office was not used to the term. So, every time we wrote the word “causal” in the course description, and this was at least ten to fifteen times, the registrar’s spellchecker patiently “corrected” this to “casual.” Of course, even today this happens. On October 11th, 2021, National Public Radio in the US announced, perhaps in an attempt to drum up more interest in the story, that Angrist and I won our share of the Prize for our “analysis of casual relationships.” Now in 2021, however, the term “causal” is well established in empirical economics: according to the same Currie-Kleven-Zwiers figure approximately 50% of current NBER working papers (a major working paper series in economics) use the term explicitly, and there are many statistics and econometrics books devoted to it (Imbens and Rubin [2015], Rosenbaum [2002], Cunningham [2020]). While this change signifies a substantial change in the focus of empirical work in economics over this time, what Josh Angrist and Steve Pischke later labeled the “credibility revolution,” it does of course not mean that suddenly the economics profession discovered an interest in causal effects. Economists have always been interested in causal effects; they just did not always call them that. Sometimes they did, and Herman Wold took the position that “The concept of causality is indispensable and fundamental to all science” (abstract, Wold [1954]), but the terminology did not catch on at the time. Language matters, though, and the new terminology signifies a change in emphasis, a change in methods, and a chance for understanding. Why did the mid-1980s provided such a fertile ground for the new econometric methods for the estimation of causal effects? There were multiple reasons. One is that there was a sense of unease with the state of empirical work [Leamer, 1983, LaLonde, 1986]. Second, the physical proximity at Harvard of Josh Angrist, Don Rubin and myself facilitated connections between econometrics and statistics that allowed us to benefit from the insights of both fields.

The course on causal inference with Don Rubin was a big success with the students, despite the initial confusion in the course description. It was not that large, probably about twenty to thirty students, but those who attended, as well as those who taught it, found it exhilarating. A number of influential papers originated directly in this course. We taught the paper by Robert LaLonde [LaLonde, 1986], leading our students Rajeev Dehejia and Sadek Wahba to write [Dehejia and Wahba, 1999]. Comments by Bruce Sacerdote in the class led to our paper on the effect of unearned income on labor supply [Imbens et al., 2001].

California, Part I

In 1997 I got turned down for tenure at Harvard University. This did not come as a huge surprise, tenure rates were very low at Harvard in general, and in the economics department few people had received tenure from the inside in recent years. There was clear appreciation for some of the work both in the department and the general profession, including the local average treatment effect paper, but not sufficient to change the norm. I did receive a number of tenured offers, including from the University of Texas in Austin and the University of California at Los Angeles. I had never spent much time in California before moving there, and I fell in love with the state. Living in Santa Monica, about twenty minutes’ walk from the beach, and a bike ride away from the UCLA campus was amazing! I got many more visitors from the Netherlands than in Boston, further reflecting the magic image California in general, and Los Angeles in particular, has in parts of Europe.

Academically UCLA also turned out to be a great fit for me. I ended up working closely with my colleague Joe Hotz, who joined from Chicago at the same time. His more structural bent was very helpful in further developing my views on causality and the direction of econometrics. I had some great students there, including Julie Mortimer, who got her first job after graduate school at Harvard University.

I also got to know Ed Leamer, who was in the business school at UCLA. Ed’s views about econometrics had not changed much since his famous “let’s take the con out of econometrics” paper [Leamer, 1983], but hearing some of the arguments first-hand, and discussing some of the subsequent developments in econometrics was enlightening. We ended up teaching a course together where we picked some influential papers in econometrics, some we liked, and some we did not like. Each week one of us would present and defend the paper, and the other would criticize it. This made for a great course from the student’s perspective, even though it was a stressful experience on my part! During my UCLA years I also spent some time at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, right next to the beach. Many years ago, John Nash, the 1994 winner of the Prize in Economics had been a consultant there.

In 2001 I moved to a different campus in the University of California system, Berkeley. This was partly for personal reasons, with my then partner, now wife, Susan Athey working in the economics department at nearby Stanford University. Berkeley was a fabulous place for me academically. It had a great econometrics group, with Dan McFadden (who had move there from MIT in the early 1990s and who had just shared the 2000 Prize in Economics with Jim Heckman), Jim Powell, Tom Rothenberg, Paul Ruud, and Michael Jansson. They were broad-minded in their interests and had formed a cohesive group that regularly had wide-ranging discussions about new developments as well as foundational issues in econometrics. In addition, and this has always been very important in my career, it had a great empirical microeconomics group. David Card had moved there a couple of years earlier, and quickly he had built a very impressive group, including at various times David Lee, Ken Chay, Emmanuel Saez, Enrico Moretti, and Raj Chetty. Part of this group was centered around the Labor Economics Center that David founded, and that attracted many doctoral students as well as a steady stream of visitors from other universities. It made for a perfect setting for me, with many colleagues to discuss theoretical econometrics who were always happy to go out for coffee to the famous local coffee shops Brewed Awakening, Strada, or the Free Speech Cafe, and at the same time many empirically oriented colleagues to get inspired by in terms of questions and problems. Berkeley was also a very collegial department in general. Over the years, the economics profession has had a poor reputation in terms of culture, but Berkeley stood out with a large number of great departmental and professional citizens. I recall a department meeting early in my days there, where I presented a tenure case, and, somewhat unusually, one of my colleagues was critical about a particular reference letter, despite that having been addressed clearly in the report. Afterwards one of the other faculty came to my office and told me I had handled the situation well. It made Berkeley feel like a great community and one of my favorite places.

My Berkeley years were very productive, despite a long commute from Stanford where Susan and I had bought a house on campus, coincidentally on the same street as Paul Milgrom and Bob Wilson, who later shared the 2020 Prize in Economics. I started a long collaboration with Alberto Abadie on matching-type and causal inference methods. We had co-authored a paper before together with Alberto’s advisor Josh Angrist, but now we started a series of papers that substantially deepened our understanding of matching and other unconfoundedness-based methods.

Back at Harvard

In 2004 my wife Susan Athey, who at the time was working at Stanford, got an offer from the economics department at Harvard University. By this time, we had an infant, so my commute to Berkeley was becoming more of a strain and we reevaluated our joint options, which ended up including Berkeley and Stanford in addition to Harvard. We decided to visit Harvard for the Fall of 2005, staying at the house of our friend Esther Duflo, who later won the Economics Prize in 2019. Many of my former junior colleagues, including David Cutler and Ed Glaeser, were now tenured and the department felt quite different from what it had been when I was there as a junior faculty member. We decided to accept the offer there, and in 2006 moved into a Victorian house just off Brattle Street. The previous owner, former Labor Secretary in the Clinton administration Robert Reich, made the cross-continent move in the opposite direction to take up a position at Berkeley.

Coming back to Harvard was a great experience. The students at Harvard were by now very interested in causal inference. The research I had worked on ten years earlier had become part of the standard first year curriculum, and the second-year courses I taught in this area became popular with participants from all over the university. Moreover, there were many colleagues and collaborators in Cambridge very interested in this area. This included Gary Chamberlain, Don Rubin, Josh Angrist (who was now at MIT), his former student Alberto Abadie at the Kennedy School, and Whitney Newey. In addition, being back at Harvard allowed me to reinvigorate my collaboration with Rubin on our book, which eventually came out in 2015 after almost ten years of on-and-off work. It also led me to find new collaborators including Nicholas Christakis.

One of the highlights of those years came from a conversation with Marty Feldstein. He had observed that other disciplines had regularly courses for faculty at their annual conferences to keep them up to date. He thought economics should do something similar. At one of the faculty lunches at Harvard he asked me if I was interested in teaching such a course, with the general theme “New Methods in Econometrics” at the National Bureau of Economic Research, where he was CEO. I was up for this, and together with Jeffrey Wooldridge I developed a three-day, 21 lecture course that gave an overview of modern microeconometrics. As the dates for the course in the summer of 2007 approached we had some trepidation because the enrollment was over 400 researchers, all faculty at universities all over the US and some from overseas. I had never had, and never again will have, such a high-quality audience. The course was a big success, ending with a standing ovation at the end of the third day, and sparked many follow-up courses. The National Bureau of Economic Research has been running courses like this, typically one day rather than three, every year, on different topics. The American Economic Association started organizing yearly courses along the same lines.

California, Part II

In early 2012 a family ski-trip to the West Coast sparked some conversations about moving back to California. Without an expansive search we quickly decided that moving back to Stanford made sense and, in the summer of 2012, we packed our belongings, and, with now three kids in tow, moved back, about a mile from where we had lived previously. Stanford was a much more challenging place for me. Unlike Harvard, where there was a lot of interest in the type of econometrics I was working on and I had many collaborators, Stanford had a very different tradition, and I had not collaborated previously with anyone. There was considerable skepticism in the economics community about the causal inference literature which was viewed as Cambridge-style econometrics, as well as in the statistics department where there was little interest in it. Moreover, the business school where we ended up had never had any econometricians on the faculty, with their primary focus on economic theory.

What made it exciting though was the location in Silicon Valley with the tech companies around. Susan had gotten interested in the economics of the tech world, which led to a stint as Microsoft chief economist. This in turn got her to start a new research area in the intersection of computer science, machine learning and econometrics, which subsequently got me interested in the questions and methods used in the new data-driven private sector organizations. These companies now routinely advertise for positions requiring skills in causal inference, including expertise in instrumental variables, regression discontinuity, causal forests, and matching, many of which were not part of the standard curriculum in econometrics ten years earlier. When I arrived at Stanford, Jas Sekhon from Berkeley asked me to do a presentation at a new interdisciplinary seminar he was setting up on general data science issues. I convinced him to make it a joint Berkeley-Stanford seminar. When he agreed we ran the seminar for a couple of years, inviting academics from various departments as well as researchers at the local tech companies. Although the seminar itself was a big success, doing it jointly was difficult with the long commute, so we ended up doing it at our separate institutions. These data, society and inference (dsi) seminars were very popular with the students as well as the faculty, opening up a window into the tech world. The move to the Bay Area later let to some of my collaborations with these companies, including a summer I spent working with researchers at Facebook and consulting arrangements with Amazon.

Now, ten years later Stanford has a strong presence in causal inference, with faculty in the business school, the statistics department, the political science department, the school for management science and engineering, the medical school, and the law school.

In early 2020 the pandemic shut down in-person teaching and seminars. Together with collaborators, I started two online seminars to fill the gap. The first was the Chamberlain seminar, named after my former mentor Gary Chamberlain, who had passed away in early 2020, focusing on econometrics. The second was the Online Causal Inference Seminar, focused on causal inference broadly defined, and including various disciplines. Both have continued even as in-person seminars have come back. They have contributed to the integration of the causal inference community across disciplines and geographies.

Epilogue

The call from the Prize Committee early in the night of October 11th in 2021 came as a big surprise. Receiving it at that time meant all three of my kids were still living at home (the oldest would leave for college 8 months later), making the celebration with my family that morning all the more special. Sharing it with David Card and Josh Angrist was another highlight. We managed to find an hour to catch up on Zoom later that day, even though it would take till the next summer for the three of us to be in the same place in person at a conference in Berkeley. Both Josh and David have been great colleagues and friends over the years, and the only disappointment was that Alan Krueger, who passed away in 2019, was not there to share it with us. Note that Alan was the only economist who had co-authored papers with all three of us.

The Prize marks a new stage in my career. While I had not felt that I was in any sense finished with my research program, it clearly creates incentives to refocus my attention on broader themes and find new ways of contributing to the development of econometric methods for economists.

References

Joshua D Angrist, Guido W Imbens, and Donald B Rubin. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American statistical Association, 91(434):444–455, 1996.

Scott Cunningham. Causal inference. The Mixtape, 1, 2020.

Janet Currie, Henrik Kleven, and Esmée Zwiers. Technology and big data are changing economics: Mining text to track methods. In AEA Papers and Proceedings, volume 110, pages 42–48, 2020.

Rajeev H Dehejia and Sadek Wahba. Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American statistical Association, 94(448): 1053–1062, 1999.

Erwin Dekker. Jan Tinbergen (1903–1994) and the Rise of Economic Expertise. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Guido W Imbens and Joshua D Angrist. Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica, pages 467–475, 1994.

Guido W Imbens and Donald B Rubin. Causal Inference in Statistics, Social, and Biomedical Sciences. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Guido W Imbens, Donald B Rubin, and Bruce I Sacerdote. Estimating the effect of unearned income on labor earnings, savings, and consumption: Evidence from a survey of lottery players. American economic review, 91(4):778–794, 2001.

Teun Kloek. Obituary: Henri Theil, 1924–2000, 2001.

Robert J LaLonde. Evaluating the econometric evaluations of training programs with experimental data. The American economic review, pages 604–620, 1986.

Tony Lancaster. Econometric methods for the duration of unemployment. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pages 939–956, 1979.

Tony Lancaster. The econometric analysis of transition data. Number 17. Cambridge university press, 1990.

Edward E Leamer. Let’s take the con out of econometrics. The American Economic Review, 73(1):31–43, 1983.

Daniel McFadden. Economic choices. American economic review, 91(3):351–378, 2001. Paul R Rosenbaum. Observational Studies. Springer, 2002.

Jan Tinbergen. Econometric business cycle research. The Review of Economic Studies, 7(2): 73–90, 1940.

Jan Tinbergen. Econometrie. 1941.

Herman Wold. Causality and econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pages 162–177, 1954.