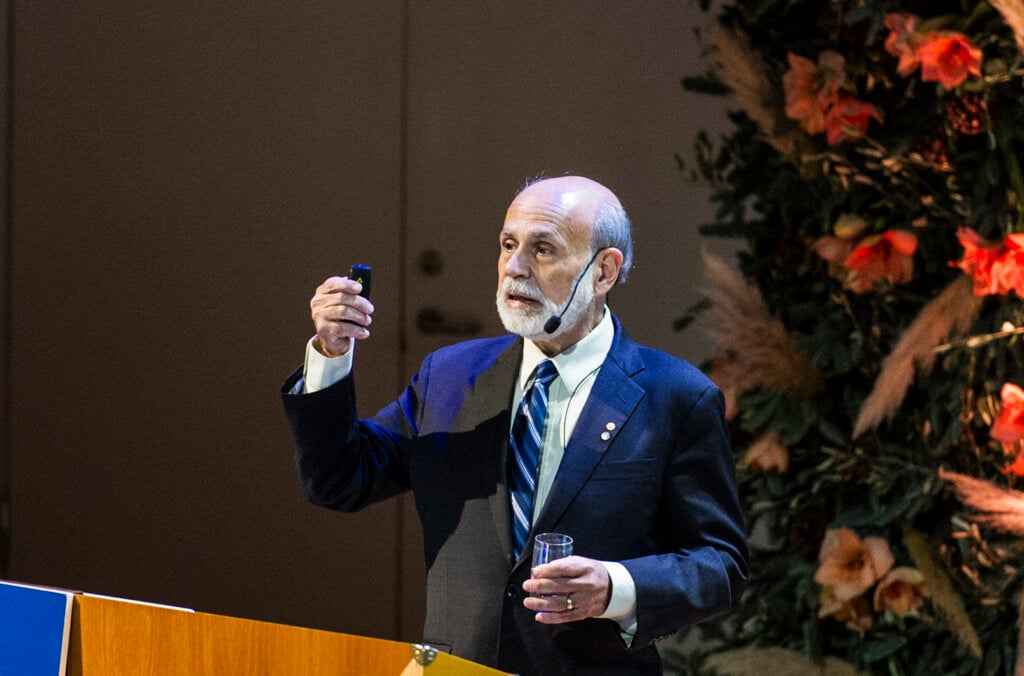

Ben Bernanke

Podcast

Nobel Prize Conversations

“It was almost an accident that I ended up in economics”

Meet economist Ben Bernanke in a podcast conversation. Bernanke tells us about his childhood interest in the origin of words, which ultimately led him to win spelling competitions as a child. He also speaks about economics and how that field unifies his interest in mathematics with social science and concerns about society.

The host of this podcast is nobelprize.org’s Adam Smith, joined by Clare Brilliant. This podcast was released on 1 June, 2023.

Below you find a transcript of the podcast interview. The transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors.

Transcript

MUSIC

Ben Bernanke clip: You have scholars going back and taking months and months and months to evaluate each decision. What you’re thinking is, well, obviously I couldn’t get all that information. I did the best I could with what I knew.

Adam Smith: Imagine being the most influential economist in the world. That was the position that Ben Bernanke found himself in when he was appointed chair of the Federal Reserve system in 2006, and then in 2008 the financial crisis hit and he had to deal with that.

In this conversation I wanted to explore what gave him the confidence to make policy as he needed to under such circumstances, given that he was, prior to his appointment, Dean of the economics faculty at Princeton University and, like many others, perhaps a rather introverted academic. Was it something about his upbringing, his education, something innate in himself?

Unsurprisingly, it’s a combination of all these things, as you’ll discover listening to this conversation with Ben Bernanke.

MUSIC

Clare Brilliant: This is Nobel Prize Conversations. Our guest is Ben Bernanke, the 2022 laureate in economic sciences. He was awarded the prize for his research on banks and financial crises. He shared the prize with Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig.

Your host is Adam Smith, Chief Scientific Officer at Nobel Prize Outreach. This podcast was produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Today Ben Bernanke is a distinguished senior fellow with the Economic Studies program at the Brookings Institute in Washington DC.

You’ll hear him speak about moving from academia to public life – and then back again, about his background as a spelling champion, and how he found his love for economics at the intersection of history and maths.

But first, Adam asks him whether his time in the public eye before being awarded the prize has informed his experience of becoming a Nobel Prize laureate.

Smith: In a few cases, for instance, Barack Obama or Bob Dylan or yourself, you’ve been living in the glare of publicity for a long time. It’s a little bit different getting the call, I imagine. I wondered whether, since you were used to it already, it made it easier to enjoy Nobel week in December when you came.

Bernanke: Yes, I think it did. I think most economists, most academics, when this happens to them, their life changes in an important way. They do a lot more public speaking, they get asked for their opinions on things which they have never studied. That’s, I think, the typical experience. In my case, I was the chairman of the Federal Reserve for eight years. and also had other roles before that. I was used to speaking in public and hearing from policy makers and the like. I was more comfortable in that respect. Frankly, my speaking engagements and interviews have not increased, since I won the prize because I was already frequently speaking in public.

Smith: Yes, of course. The experience of being in Stockholm, I think many laureates find rather overwhelming. By the end of Nobel week they’re absolutely exhausted. Was that the case for you? Did you find yourself exhausted or were you fresh and ready for Christmas?

Bernanke: It was a very busy week. There were things going on every day, multiple interviews or ceremonies or dinners. I think my one disappointment was that my wife and my guests got to see more of Stockholm than I did. I would be going to various events and my family was able to go to a museum or take a cruise or otherwise see the city.

Smith: Let me just take you back there for a moment by playing a clip from the award ceremony.

CLIP from the award ceremony

Bernanke: It was very exciting, of course. You have to cross the stage to go accept the award. I was worrying that I might trip or do something else embarrassing. But of course, it was the culmination of the week. It was a quite impressive scene with the entire audience, all the men dressed in white tie and tails and the women in gowns. Such a nice formal occasion with the music and hearing my fellow laureates. It was obviously a very great moment. But, again, it was only part of that whole week of celebrations and interviews and the like.

Smith: What was emphasised in the presentation speech was the fact that you as an academic had found yourself in the position of being a practitioner and how you had been called upon in 2008 to act in a way that pretty much had to save the global economy, which is a very unusual position to find yourself in. I wanted to explore a little bit how, I suppose, an academic who is generally presumed to be a rather shy individual by society at large, suddenly finds the confidence to be able to act in that way.

Bernanke: Yes, I am by nature introverted. But necessity creates its own requirements. It was obviously a very difficult situation. My research helped prepare me to think about what was happening since my work was about the depression, about financial crises, about their effects on the economy. Obviously, here was an example in real time of a global financial crisis. It was difficult, but again, it was absolutely essential that we, I say we because I had great colleagues, both the Secretary of the Treasury, Hank Paulson, later Timothy Geithner, as well as many staff and colleagues at the Federal Reserve to help. I was rarely out there by myself. I was usually had some kind of support. Obviously it was incredibly important to voice my views and to let people know what we’re doing. I once said that central banking is 98 per cent talk and 2 percent action. The talk part was very important, both in policy and in politics.

Smith: It’s been commented of you that you’re somebody who likes to speak last, not first, which is perhaps not a usual trait in a leader, but perhaps one to be desired. Does that ring true?

Bernanke: Yes, I think that is true. For example, in the monetary policy meetings of the Federal Reserve, there are many policymakers around the table. I would, as a matter of routine, ask everyone else to speak first. I would then summarize what I had heard, and then make my own recommendation. That was indeed the practice that I followed. Prior to being a policy maker, I was an academic and I was for seven years the chair of the Princeton economics department. Once again, you had to deal with people with high intelligence and strong opinions. Coming to a consensus, I think was very important. From the outside, it often seems to the public that the chair of the Federal Reserve or the president, whatever leader we’re talking about, is sort of acting as an individual. That’s never true. It’s always important to build consensus within your organization or within your government and to listen to what other people have to say that will inform your decision and point out potential pitfalls, for example. I think the only drawback of that approach is that sometimes it takes a little bit longer to come to a decision than otherwise. On a few occasions when I felt that it was necessary, I took unilateral or very quick decisions. But whenever possible, it was both helpful and confidence building to try to get everybody’s input and to try to build a consensus.

Smith: Just from a personal perspective, it must be a little bit terrifying that if you, on a Monday, as you did in 2008, you announce a three quarter percent reduction in interest rates in order to stem the tide. Sure, you’ve made the decision based on everything you know, but it must be scary.

Bernanke: I think terrifying is too strong a word, but it was certainly anxiety producing. Again, one of the elements of a financial crisis is, first of all, it’s very hard to predict. We did not predict a crisis of the magnitude that happened months in advance. Almost by their nature, financial crises are very hard to predict because they do depend on confidence and on random events that may occur. You’re operating in what Timothy Geithner used to call the fog of war, that there’s always many things happening, you cannot possibly know everything you would like to know. What always happens of course is that 10 years later you have scholars going back and taking months and months and months to evaluate each decision and what you’re thinking is, well, obviously I didn’t have all that information. I couldn’t get all that information. I did the best I could with what I knew. Inevitably that creates a lot of anxiety, a lot of concern. But frankly, I was just so focused on what needed to be done and on trying to build a consensus with my colleagues that I didn’t have a lot of time to reflect on the emotional aspects of this. I had good support from my family and again from my colleagues and we just took one step at a time.

Smith: I suppose that in that position, it takes a lot out of all of you.

Bernanke: It does. Certainly, I had very irregular hours and very long days, weekends. I think the most important thing that my family could do would be to provide a refuge, just normalcy, where you could leave the chaos and have some place to go. At work you would make some $10 billion decision and then we’d come home and discuss the water bill with your wife or put out the garbage. It created sense of, first of all, of what you were working for, that is, for not just my own family but for families across the country, but also a sense of refuge and a sense of support that was unconditional and that I knew I had people on my side in that respect and that was always good. My wife had her own interests. She’s a long-time teacher and in 2008 of all time she founded a small private school in Washington which she’s still running today with innovative teaching techniques and she was doing that. She had her own things that she was concerned about, but she was always there. We always, when I was available, we would have dinner together and the like. That is very important for anybody in a high stress position, whether it’s public or private.

Smith: Actually, that brings me to a second clip I’d like to play. This is President Obama speaking about you. Let’s listen to President Obama.

CLIP with President Obama

Smith: First of all, it must be nice listening to that again.

Bernanke: Yes, and I would just like to say that one of the things that helped me considerably was that both President Bush, who appointed me originally, and President Obama, who reappointed me, so a Republican and a Democrat, were very supportive throughout the crisis. On the one hand, gave us what we needed, and on the other hand, respected the independence of the Federal Reserve to make decisions, especially monetary policy decisions. I was very lucky in that respect. I was gratified that President Obama saw fit to reappoint me because at the time that he reappointed me, which was in 2009, the crisis had been calmed, but the economy was still in very bad shape. A different president might have said that’s not a great record. I need somebody different, but he gave me the chance to continue to finish the job, so to speak. Again, I was very grateful to do that, even though part of me said, another four years of this is going to be a lot of stress. But I did have very good relationships with both presidents that I served under.

Smith: Very different administrations to work with. So again, it speaks to your ability, I guess, to talk to lots of different sorts of people and gain consensus.

Bernanke: I’m just not all that politically inclined. I’m more interested in the analytics of the economics, of the implications of economic decisions for the wellbeing of the broader public. I tried to avoid, when I was chair, I’d never voted, for example. I just felt that I needed to take a neutral political perspective. Again, this was the consensus building part that we’ve been talking about, which is, I frequently had to testify before Congress. I testified some 80 times before Congress. Of course, you had to deal with very different perspectives on the two sides of the aisle. I couldn’t always satisfy them, and sometimes they were very critical. But I did my best to try to answer in a straightforward way and to try to explain what we were doing, why we were doing it, and why it would be beneficial to follow that strategy.

Smith: That reappointment by Obama does speak volumes again about the confidence that he and others had in you, because he obviously had to project confidence himself. Reappointing you was quite a vote of support.

Bernanke: Yes, I interpreted it that way. There had been some tradition, going back to Alan Greenspan, who was reappointed, I think some four times by both Republicans and Democrats, I think there had been some tradition because the Fed, like other major central banks, is supposedly independent of the executive branch. Chairs who had done at least a reasonably good job were typically reappointed by the president, even if parties had changed in the meantime. In reappointing me, he was not setting a new precedent in a sense, but it was a vote of confidence, obviously given the circumstances of the time. I will say that he was very engaged, particularly, The Fed, besides monetary policy and financial crisis, financial stability issues, also has a regulatory role. In 2010, there were major regulatory reforms in the United States, which I, as the Fed chair, had considerable input to, and the Treasury Secretary and the like. The president would call us to the White House to talk about those things as well. He was engaged. I was, of course, gratified that he saw fit to reappoint me.

Smith: He mentioned your pharmacist teacher combination upbringing. You grew up in South Carolina, in Dillon, South Carolina. What was it like, the home life?

Bernanke: All my grandparents, all four of them were immigrants from Eastern Europe. They all came originally to New York and other large cities. My father’s father was a pharmacist also, and he moved to Dillon in order to buy a pharmacy that was for sale there, and he brought his family with him. Some cultural mismatch there. We were one of the very few Jewish families in that town. That being said, I made friends there and played in the high school band and participated in other activities. My father and his brother were pharmacists. They owned the store together. They bought it from my grandfather who had started it. They were important people in the town because I think in the entire town, we had one doctor, and so people would frequently come to the pharmacy and ask for simple medical advice or for nutritional advice etc. My father and uncle who were called Dr. Phil and Dr. Mort, had that kind of relationship. My mother was a teacher for a while, but when I was growing up, she was mostly a housewife. She stayed at home or she worked part-time in the drug store doing various jobs. My mother was there most of the time and it was a good home life. I had two younger siblings, a brother who is now a lawyer and a sister who is an administrator in a music college. It was a small-town childhood, and in that respect, similar to many other people. Having said that, there was quite a bit of culture shock when I left there and went to Cambridge, for example, to go to college.

Smith: Indeed, yes. From Dillon to Harvard, yes. Do you think actually it was a blessing to have been brought up in small town in South Carolina, rather than in New York, for instance, where it could have happened?

Bernanke: There were frankly pluses and minuses. I think on the one hand, I mentioned the cultural mismatch. I went to public schools in Dillon, which were probably not as good as the best schools in New York, for example. But on the other hand, living in a small town does have a lot of advantages. I worked various jobs. I worked construction. I worked waiting on tables. I worked in the drug store. I had friends, obviously, who had worked on farms and agricultural work. I think one thing that I got out of being in Dillon, besides just sort of a sense of what broader America is like, outside of the big metropolises, besides that, I think I got at least a sense of how hard it is for the ordinary person to put food on the table. Working as a construction worker, unskilled worker, as I did for one summer, is very hard, didn’t pay much. I said this is a hard way to make a living. Waiting on tables was also long hours. Sometimes you had customers or customers who didn’t tip. Again, it was a useful education for me when I was Fed Chair. Of course, I was always looking at the numbers. Here comes a number about how many jobs were created last month, for example. On the one hand, as an economist, I’m looking at that number and trying to think about how it fits into a broader economic picture. But on the other hand, having grown up in a small town, not a very rich town, economically very stressed place I could think about the real families, real people that those numbers represented. That was important to me.

MUSIC

Smith: You were also a stellar student. You seemed to excel easily. Or was it that you had a very good work ethic from a very early age?

Bernanke: I just liked to learn. I think I had the ability. I never had any problems in school. I was the state spelling champion in sixth grade. Later I won a state-wide award that allowed me to make my first trip, foreign trip, a short tour of Europe. when I was a senior in high school. Frankly, when I went to college, when I went to Harvard, I was fairly shocked because I found that I actually had to study, which I had never done before. I was faced with a much more extensive and competitive environment than I had been used to.

Smith: I’ve never participated in a spelling bee, but I’ve seen them televised and they look absolutely terrifying in fact.

Bernanke: Like everything else, they’ve become professionalised. When I was competing in the state, I actually won the state spelling bee even, and went to Washington to compete in the national spelling bee. I didn’t really study for it. Again, I didn’t sit and memorise long lists of words. I think now the competitors basically put their lives on hold for months in order to study long lists of difficult and obscure words. Like I said, it’s sort of become more professionalized than it was when I was, many years ago, when I was involved in that.

Smith: Does this ability to spell indicate a particular love of words? You write quite a lot of books. Are words very important to you?

Bernanke: Let me just first say that spelling is a sort of unusual talent, that not everybody has it. Some of the people who don’t have it include great authors and very smart people. I’m not saying it’s correlated with ability in any way, but I always have been interested in words. Even as a young child, I was interested in where words came from. I would listen to some expression, some idiom. It doesn’t really make sense. Where did that come from? My life is much better now because now I can look on my phone and it will tell me where the expression was originated or where the word came from. When I was growing up in Dillon, we didn’t have such easy references. But I’ve always been interested in the origins of words. I feel always very unwillingly kind of irritated when journalists and others misuse words or spell them wrong or the like. I know that’s not rational, but it’s just something that I have from my childhood.

Smith: Do you read a lot?

Bernanke: I read all the time. I read three or four books a week, probably.

Smith: Gosh.

Bernanke: Of all different types. The thing I would say is I don’t read much economics. I read mostly either fiction, some of it junky fiction, like detective novels, but other kinds of fiction as well. Then I’ve always tried to be broad in my interest, readings about science or mathematics or biology or astronomy, whatever other fields are interesting. Right now, we have a lot of interesting things happening in artificial intelligence, for example computing. While I’m obviously not an expert or a specialist in any of these fields outside of economics, I do like to keep up. I like to read good popular writers who can explain in reasonably clear terms what’s happening in these different fields. I do have very eclectic tastes and I think I could have been something else other than an economist. It was almost an accident that I ended up in economics because I liked some courses that I took at Harvard. I do have broad tastes and I do like to read and it fits with my introverted personality that rather than going out to a big party, I would rather stay home with the book if at all possible.

Smith: Would you identify one book that has particularly influenced you?

Bernanke: I don’t think so. I could give you many books that I found fascinating. It’s a very esoteric example, but there was a computer scientist and philosopher named Douglas Hofstadter who wrote a book called Gödel, Escher, and Bach, which was about self-referential thinking. Essentially, it sort of tried to get into the meaning of intelligence and consciousness from a philosophical point of view and a mathematical point of view.

CLIP reading from Gödel, Escher and Bach:

“If words were nuts and bolts, people could make any bolt fit into any nut: they’d just squish the one into the other, as in some surrealistic painting where everything goes soft. Language, in human hands, becomes almost like a fluid, despite the coarse grain of its components.”

Bernanke: A very obscure book. Most people don’t find it very interesting. I just found it very stimulating. I read it many years ago. But I’ve read many great books since then. I’d have to sit down and try to make a list. I feel anyone I told you would be offending or leaving out things that were important.

Brilliant: Adam, Ben Bernanke’s research has focused on the Great Depression. Could you tell us a little bit about that period of history?

Smith: Yes. The Great Depression was the longest and deepest downturn the modern economy has ever seen. It began in 1929 in the US, at the end of a decade of relative affluence in the US, the Roaring Twenties, and then suddenly this downturn began. Then it went on right up and into the Second World War, only stopping in 1941. It lasted over a decade, and although it started in the US, it spread around the world, causing misery for millions and having profound consequences that extend, I suppose, up till this day. It was a period in which there were massive rises in unemployment and massive decreases in production. I suppose for most of us, it’s some of the iconic images from that time that stick with us. Pictures of very long lines of people trying to get a job, people just desperate to find work of any sort. Many films that capture the misery of that time from John Steinbeck to for instance, It’s a Wonderful Life.

Brilliant: Do you know, I’m actually embarrassed to admit I haven’t seen that film, Adam.

Smith: What do you do at Christmas?

Brilliant: We’re watching Elf at Christmas.

Smith: Nevertheless, I’m sure you’re familiar with the iconic scene from it, in which people are massing outside the doors of a bank trying to get their money back. One of the things that happened during the Depression was that many banks failed. In the end, in the US, it led to a complete collapse of the banking system in 1933. That collapse of the banking system is something that Ben Bernanke, in particular, has identified as being important in the Great Depression.

Brilliant: What have been the consequences of Ben Bernanke identifying the importance of that?

Smith: It’s changed, I suppose, the way that people look at bank failure. What he saw was that the closing of banks, which before his work had perhaps been seen more as just a consequence of the Depression, actually had a causative influence, that the fact that there were no longer banks around who could provide loans to people meant that people couldn’t get credit to build their way back out of the recession. That just prolonged the thing. Now people realise that even in the midst of crises, it’s very important to preserve the credit system. Central bankers around the world these days try very hard to preserve the integrity of banks. Central banks tend to act as a lender of last resort, so that even if a bank is about to collapse, there’s somebody who will guarantee that the depositors can get their money back. That’s playing out around us in real time, unfortunately, at the moment. We’ve recently seen three commercial banks in the US fail, which wasn’t expected. The role of policy makers in reacting to that sort of situation is very much in the news at the moment. It’s very interesting to listen to Ben Bernanke talk about what got him interested in this huge topic of the Great Depression. Let’s take a listen to that.

Bernanke: The Great Depression was this global catastrophe where you had all these workers and factories, unemployed and not producing when, in some sense they could have been producing. It’s just a big puzzle, because the underlying paradigm of economics going back to Adam Smith in 1776, which has also been very influential in modern economics, is that market economies will make good use of resources. Prices will direct resources into the most productive uses and give people incentives to find the most useful occupations and the like. That world of market clearing where prices are signals, etc, doesn’t fit very well with the idea that, for more than a decade, we had unemployment ranging from, depending on how you measure it, ranging from 15 to 25 percent in the United States. At a time, by the way, when we didn’t have unemployment insurance and other kinds of things to help the unemployed make do. I always found it to be just a fascinating puzzle. By the time I got to grad school, there were obviously a lot of theories out there, and none of them were completely satisfactory. Let me tell you a quick story. My mother’s parents, my grandparents, who lived in Charlotte, North Carolina, I used to visit them as a young child. I used to visit them in the summer. I’d sit on the front porch, particularly with my grandmother, and just she’d tell me about her life. She told me once about when she lived in Connecticut in a town that had shoe factories. The shoe factory shut down during the Depression because there wasn’t enough demand. She told me that many children in that town went to school with ragged shoes or maybe even no shoes at all. I said, well, why would a six-year-old child? I said, why would they do that? and she said, well, because their fathers had lost their jobs when the shoe factories closed. I said, wait a minute, why don’t they just open up the shoe factories and make shoes for the children? She said, no, it doesn’t work that way. I just thought that was just so incomprehensible and why resources are sitting there and not being used. I read Grapes of Wrath and other depression related stuff even through high school. When I got to graduate school and began to think about what fields I was interested in, I became convinced that macroeconomics and monetary economics was really worth studying, because that would help you understand big events like the Depression, which not only created an enormous amount of economic hardship, but arguably led to the ascent of Hitler and World War II and all that followed from that. These are very important issues. I couldn’t see how you wouldn’t at least be interested in those questions.

Smith: The interest in the depression was there, and then the tools were provided by economics to address what happened. Were you surprised by what you found? Which was that banks, the role of banks, the stability of banks was much more important than had previously been assumed. It was that they really had a deciding factor.

Bernanke: The prevailing story when I was in graduate school was that the depression was caused by a collapse of the money supply, which in turn led to falling prices and to other problems. I think there’s actually some truth to that because the gold standard was prevailing at that time and it collapsed after World War I brought down money supplies and prices and was a powerful depressing force. People like Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz documented the relevance of the collapse of the money supply to the economy. If you just read about the depression, if you read diaries or memoirs of the depression, one of the other aspects of it is just simply the financial distress. Not just falling prices, but the fact that businesses were failing, banks were failing, individuals were obviously in huge financial distress. They couldn’t pay the mortgages. There was the rate of failure of delinquency on home mortgages in the depression was probably two or three times what it was during the global financial crisis. That was a horrible period. It seemed to me, in some sense, obvious that the breakdown of the credit system, which at that time most credit was provided by banks, and about a third of all the banks in the United States, thousands of banks failed during the depression, that the breakdown of the credit system would have to be a negative for the economy. I don’t dispute the fact that monetary issues were important. In fact, when I was Fed chair, obviously, I tried to ensure that monetary policy was supporting economic recovery. It really did seem to me that there had to be some influence of the financial distress from bank failures and debtor bankruptcies and firm failures and the like. I think there are not very many good aspects of the global financial crisis, but one thing I think there weren’t very, you can’t explain that crisis of 2008 by monetary forces. That was clearly a crisis that was brought about by a collapsing financial system and widespread default and widespread financial distress. Ironically, the experience of 2008 kind of reinforces the idea that these issues must have been important in the 1930s as well. What I hope I did was to try to add a dimension to our understanding of depression. I feel now that I understand the I feel that I understand why it was as bad as it was and why some policies helped to improve it and others did not. I at least have been able to answer my six-year-old question to my own satisfaction at this point.

Smith: Indeed. Do you think, given recent events with Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse for instance, do you think we’re always teetering on the brink of these things?

Bernanke: Let me say yes and no. Yes, in the sense that confidence is always an ephemeral thing. If there’s a sufficiently widespread loss of confidence or other unexpected events then you can have a lot of financial distress. One thing I’ve learned is to never say never. It’s always possible. But many of the warning signs that we saw in the depression and at the early stages of the global financial crisis, like large quantities of bad debt, like subprime mortgages and a credit boom, weakness in a variety of financial institutions. We’re not seeing that at least so far in in the current system. Since the global financial crisis, there have been a lot of changes in, for example, capital requirements and the like that have made banks stronger. Now, again, I think you should never say never. In the United States, unlike Europe, banks actually provide less than half the credit that people and firms use. A lot of credit is provided by other kinds of institutions, which are collectively known as shadow banks, which are not official banks, and which are much more difficult to monitor, and which are much less regulated. I’ve been concerned about those ever since the financial crisis. I don’t think that the regulatory strengthening that was done for banks has been quite as effective and comprehensive in the case of shadow banks. There probably could well be things happening in the shadow banking system that the regulators and policymakers are not aware of. I think vigilance is always important. You should always assume that financial instability is a possibility. You should always be on the alert. You should be always trying to find ways to strengthen the financial system. At the moment, I think we’ll see. But again, never say never. It looks like the response of the Fed and the Treasury and FDIC has stopped what seemed at the time to be some risk of contagion to other banks and at least so far we haven’t seen that kind of contagion.

Smith: Yes, and again it must be nice to see your own approach to policy vindicated.

Bernanke: I think that if you say my approach to policy means that financial stability is very important for the economy, which is a one-sentence summary of my research, I think that has clearly been vindicated. I certainly have plenty of critics even today about exactly how we approach that and why we didn’t identify the crisis earlier and what other steps we might have taken. I myself am not completely satisfied with all the regulatory changes that have been made. There’s plenty of room for debate and discussion. But the idea that financial stability is important for the economy, which surprisingly enough, when I was first working on these issues back in the 80s, was not a mainstream idea, I think it has to be well accepted by this point.

MUSIC

Smith: In a way, your career describes as kind of an arc that you’re an academic, you become Dean of the Economics Department at Princeton, and then you’re thrust into this position of having to be doing as well as thinking, and now you’re back to being an academic again. What’s it like to see those different sides of life as an academic and then return to academia?

Bernanke: The experience of being a policymaker, and it’s only a minority of economists who get that opportunity, certainly influences the way you think about economics and affects the decisions about what research you’d like to do and the like. I’m glad to be back in a research mode. I think that I got a very difficult but also informative experience as a policymaker. I think I’m ready now to reflect and to write and to try to distill the lessons that I learned in that experience. Particularly at this stage in my life, when I’m no longer a young professor scrambling to publish or perish and I can write what I want to write, I think it’s actually a very good life because you can work on what you want to work on. If something doesn’t work out, it’s not a disaster. But I’ve actually done some work since my policy time, which I’m proud of. I think it’s been good and it’s contributed to policy debates and the like. I hope to continue to do that, both in articles and in books.

Smith: I mean, obviously curiosity came naturally to you and it seems to continue unabated. It’s a marvellous gift to have.

Bernanke: My curiosity is intellectual curiosity. I like concepts and ideas. I’m probably not so curious about, I don’t know, mechanical things, for example. I’m not adept in fixing things around the house, for example. In that respect, I’m probably quite different from my physics laureate colleagues, and… But I just enjoy ideas and enjoy conceptual thinking. I thought in high school that I might become a mathematician, but it was a little bit too withdrawn from social life for me. I found economics to be an area that combined quantitative mathematical and abstract thinking with social science, concerns about society, concerns about the public. It was a good compromise for me in terms of my interests in general. But I’ve always been just very stimulated by ideas and I continue to be like to follow ideas. That’s why I think we mentioned earlier artificial intelligence. I think some of the directions that science and technology are going today are extremely interesting. I don’t pretend to be a contributor or even fully understand these developments. I like to follow them closely.

Smith: But it is what you just said is so common to hear among economists and economics laureates that they’d thought of doing maths and then they realised, if you like, that you can study and understand and perhaps even tweak social issues through maths and that by becoming an economist.

Bernanke: It also interacted with my interest in, I’ve always been interested in history as well. I think that understanding the economics of how things work really sheds a new dimension on all of these important periods. What was the economics behind World War II? I read a very dense but very interesting book by Adam Tooze about the war economy in Nazi Germany. How the economy worked in Germany and how the ability of the Nazis to develop weapons and get oil and develop ammunition supplies, etc. supported or constrained their ability to wage war. Ultimately, economics is a very important component of warfare, social conflict and opportunities that ordinary people have. A knowledge of economics really throws a new light on history that if you don’t know economics, you think it’s all about kings and queens and battles. There’s a lot more to history than that. Economics captures how ordinary people live and why they live the way they did, which is not often left out of history books.

Smith: Absolutely, yes. It becomes a lens with which to analyse everything.

Bernanke: That’s right, yes.

Smith This has been very informative and a huge pleasure. Thank you very much indeed.

Bernanke: Thank you.

MUSIC

You just heard Nobel Prize Conversations. If you’d like to learn more about Ben Bernanke, you can go to nobelprize.org, where you’ll find a wealth of information about the prizes and the people behind the discoveries.

Nobel Prize Conversations is a podcast series with Adam Smith, a co-production of Filt and Nobel Prize Outreach. The producer for this episode was Karin Svensson. The editorial team also includes Andrew Hart, Olivia Lundqvist, and me, Clare Brilliant. Music by Epidemic Sound.

Serving as head of the Federal Reserve certainly put Ben Bernanke in the spotlight. We’ve spotlighted over a dozen brilliant economists in earlier episodes. Find them on Acast, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Thanks for listening.

Nobel Prize Conversations is produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.