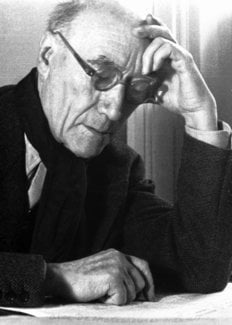

André Gide

Biographical

André Gide (1869-1951) came from a family of Huguenots and recent converts to Catholicism. As a child he was often ill and his education at the École Alsacienne was interrupted by long stays in the South, where he was instructed by private tutors. His Les Cahiers d’André Walter (1891) [The Notebooks of André Walter] opened the door to the symbolist literary circles of the day, but the decisive event of these years was a journey to Algeria, where a severe illness brought him to the verge of death and precipitated his revolt against his puritanical background. Henceforth his work lived on the never resolved tensions between a strict artistic discipline, a puritanical moralism, and the desire for unlimited sensual indulgence and abandonment to life. Les Nourritures terrestres (1897) [Fruits of the Earth], the drama Saul (1903), and later Le Retour de l’enfant prodigue (1907) [The Return of the Prodigal], are the chief documents of his revolt.

A result of Gide’s revolt was the unprecedented freedom with which he wrote about sexual matters in Corydon (privately published 1911, public version 1924), his autobiography Si le grain ne meurt (1924) [If It Die …], and Gide’s lifelong diary Journal 1889 à 1939 (1939), Journal 1939 à 1942 (1948), and Journal 1942 à 1949 (1950).

Gide divided his narrative works into soties such as Les Caves du Vatican (1914) [Lafcadio’s Adventures] and classically restrained récits, for example, La Porte étroite (1909) [Strait is the Gate] and La Symphonie pastorale (1919). The only work which he considered a novel was the structurally complex and experimental Les Faux Monnayeurs (1926) [The Counterfeiters].

Until the twenties Gide was known chiefly in avant-garde and esoteric literary circles (he was one of the founders of La Nouvelle Revue Française), but in his later years he became a highly influential, although always controversial figure. He travelled widely. His trip to the Congo led to a scathing report on economic abuses by French firms and resulted in reforms. If in the thirties Gide put off one part of the public by his sympathies with communism, his disillusioned report of his journey to Russia, Le Retour de L’U.R.S.S (1936), scandalized another. Gide’s interests went far beyond the confines of French literature. He translated Shakespeare, Whitman, Conrad, and Rilke. He was an influential literary critic (Prétextes, 1903; Nouveaux Prétextes, 1911) and was especially attracted to problematic writers like Dostoevsky, about whom he wrote a book (1923).

Among Gide’s last work was Thésée (1946), like the earlier Oedipe (1931) the reworking of an old myth. Gide’s collected works have been published in fifteen volumes (1933-39).

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

André Gide died on February 19, 1951.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.