Patrick White

Article

Patrick White – Existential explorer

by Karin Hansson*

This article was published on 29 August 2001.

Nobel Prize

When Patrick White was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973, the Swedish Academy’s commendation referred to the author’s epic and psychological narrative art as having introduced a new continent into literature. This standpoint may seem surprising now, but at that time it was a generally valid Swedish (and European) perspective – up to then literary criticism had largely ignored post-colonial writing and other new literatures in English. In many non-European countries, however, Patrick White was a well-known name, and he had already won prestigious prizes. His Nobel Literature Prize was the first to be awarded to an Australian, it is true, but the quality of Australian literature in general and of Patrick White’s writing in particular had long been recognized, not only by Australians, but also outside the country. To White’s fellow-countrymen, the Nobel Prize confirmed his status as a major novelist whose fiction had, for more than twenty years, been regarded as an important

With the prize-money he created the PATRICK WHITE LITERARY AWARD to encourage the development of Australian literature. The committee has been instructed to give precedence to authors whose writing has not yet received due recognition. Among the winners have been Christina Stead, Randolph Stow, Thea Astley, and Gerald Murnane.

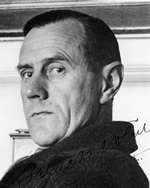

A fierce disdain of the commonplace.

© Bonnier Archives

European or Australian?

It is important to recognize White’s conflicting loyalties to Europe and Australia. In many respects the European background and influences are obvious in his writing. After spending his first school years at private schools in New South Wales, he was sent at the age of thirteen, very much against his will, to Cheltenham College in England. There he spent a “four-year prison sentence,” according to his autobiography, Flaws in the Glass (1981). All the same, after a couple of years as a jackeroo on his uncle’s sheep station in Australia, he chose to return to England and Cambridge in order to study modern languages. He also spent some vacations in Germany and developed a lasting interest in German and French literature.

After taking his degree, intent on forging a career for himself as a writer, he settled in London to write novels, plays and poetry. His first novel, Happy Valley (1939) was praised by some British critics, but the next, The Living and the Dead (1941), forced out prematurely because of the impending war, was a failure even according to the writer himself. The same year he received his Royal Air Force posting as an Intelligence Officer in the Middle East and Greece. His experiences in the Western Desert led him to the reading of Australian explorers. Eire’s Journal of Expeditions into Central Australia evoked in him “the terrible nostalgia for the desert landscapes,” a feeling that was to influence his later novels, above all Voss. His first visit to his native country after the war made him decide to settle in Australia. He was then nearly forty years old.

Merging external Australian details with abstractions from his European experience.

© Australian Tourist Commission

Even though all the later novels are wholly or mainly set in Australia, they belong to the European epic tradition insofar as they are inspired by and based on Greek mythology, Judeo-Christian mysticism, C.G. Jung’s psychology, and the Joycean stream-of-consciousness technique. White has quite often been compared to the greatest among Russian and French novelists. After his return, external Australian conditions and details merged with abstractions from his European experience. In consequence, tensions both between Europe and Australia and between a “real” and a “symbolic” Australia became significant. There is also an obvious love-hate relationship with the country of his childhood. His disappointment in the materialism and shallowness of what he terms the Great Australian Emptiness, is very marked in the essay “The Prodigal Son” (1958), in which he expresses serious misgivings about the country’s future. This attitude also comes to the fore in his writing, and caused many critics to accuse him of elitism and intellectual snobbery. White’s “Australianness” and commitment to the continent are nevertheless generally recognized in the sense that his return brought true colours back to his palette and, in The Aunt’s Story (1947), introduced a new style into his canon, initiating novels of depth and dedication.

The first phase

The Aunt’s Story and The Tree of Man

For many reasons, the two novels The Aunt’s Story and The Tree of Man can be considered as the initial phase of a novel sequence. Unlike the earlier books, they are concerned with the most fundamental issues of humanity, such as the relationship between madness and sanity, reality and illusion, and the problem of communication in existential matters. For the first time, the idea of movement is structurally and consistently combined with the search for ultimate truth, the quest. Here, as in his later books, the characters are divided into two categories from a spiritual point of view: the living and the dead. The true questers are explicitly heading for salvation or damnation in a religious sense, not merely for an intenser form of life. They are opposed to the materialistic characters, who are rooted in social conventions, dreaming of possessions and gentility.

The Aunt’s Story presents the quest of Theodora Goodman, a spinster, “dry, leathery and yellow.” She is the first in a series of alienated, humble seekers in search of a true reality behind the appearances of social life. Like Theodora, they are all facing the choice “between the reality of illusion and the illusion of reality.” Increasingly estranged from ordinary life, she passes through a series of heightened moments of insight and awareness, “epiphanies” to use James Joyce’s term, leading up to final illumination. The question is asked whether spiritual illumination is compatible with the retention of selfhood and mental sanity. Theodora Goodman’s ending is characteristically ambiguous. To the world, she appears to be mentally deranged when she is finally led away by Doctor Holstius, whose name hints at a sense of ultimate wholeness. Holstius knows that “lucidity isn’t necessarily a perpetual ailment,” and he summarises the lesson she has learnt: “You cannot reconcile joy and sorrow. Or flesh and marble, or illusion and reality, or life and death. For this reason, Theodora Goodman, you must accept.” Like all the later questers, she experiences that “for the pure abstract pleasure of knowing, there was a price paid.”

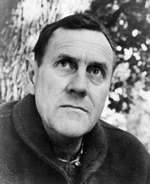

Searching for the ultimate truth.

© Bonnier Archives

The changes in setting between the various parts of the novel are related to the mental development of the protagonist to such an extent that it is unclear whether Theodora’s odyssey carries her across oceans and continents in a physical sense, or whether the whole journey takes place in her troubled mind. There is a significant epigraph from Olive Schreiner for the third part of the novel: “When your life is most real, to me you are mad.”

The Tree of Man was the first novel to win international acclaim. On the narrative level, it deals with the hardships of a farming couple, Stan and Amy Parker, in New South Wales. The frame is that of the conventional pioneering saga, albeit with biblical overtones and associations. Stan is one of White’s characteristic seekers, and his spiritual capacity is set off against Amy’s conventional attitudes. Stan “respected and accepted her mysteries, as she could never respect and accept his.” The story contains the typical features of Australia’s natural trials and disasters, such as bushfires, drought, and floods, but above all it enacts the psychological drama of Stan’s desire to understand the purposes of God, which “are made clear to some old women, and nuns and idiots.” The background and aim of the novel are indicated in White’s essay “The Prodigal Son”:

It was the exaltation of the “average” that made me panic most, and in this frame of mind, in spite of myself, I began to conceive another novel. Because the void I had to fill was so immense, I wanted to try to suggest in this book every possible aspect of life, through the lives of an ordinary man and woman. But at the same time I wanted to discover the extraordinary behind the ordinary, the mystery and the poetry, which alone could make bearable the lives of such people, and incidentally, my own life since my return.

So I began to write THE TREE OF MAN.

Like Theodora, just before he dies Stan is granted a moment of illumination and universal harmony, finally understanding that “One, and no other figure is the answer to all sums.”

The second phase

Voss, Riders in the Chariot, and The Solid Mandala

If the novels of the first phase focus on one single protagonist, those of the second are built up around more than one central character; two, four, and two respectively. All of them are presented as being exceptional, different, puzzling, or even repulsive. In this respect, White’s theme is the reverse, namely to show the ordinariness in which man’s divinity is contained behind outward exceptionality. The characters are also conscious of their otherness in a way Theodora and Stan were not, and they seem to accept it to the extent that they even seem to take a pride in it. All three books have a dimension of religious mysticism and contain celestial images related to different myths and archetypes: the Comet, the Chariot, the Sun and the Moon. The mandala belongs to the same sphere. In this structural system we find symmetrically grouped principal figures such as the circle, the square, and the cross. In all three novels, there is a general movement towards a centre representing wholeness, psychological and religious. We also find elements from the mythological beliefs of the Australian aborigines.

Voss is based on the story of the German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. Like him, Voss intends to cross the Australian continent from east to west with a group of men. The three stages of his quest are represented by coast/city, bush, and interior/desert, respectively. Voss, dominated by willpower, megalomania and egocentricity, has been compared both to Faust and Hitler. The desert, he thinks, will prove a worthy opponent when he wants to demonstrate his superhuman status. Before he sets out he meets Laura Trevelyan, a spinster who makes a strong impression on him. During his journey into the desert he becomes transformed through her telepathic influence as they communicate in dreams and delirious visions. In the end, he is humbled through Christ-like suffering and death. Laura believes that his union with the desert of the interior implies a different kind of victory: “Voss did not die.” He is still there, it is said, in the country, and always will be. “His legend will be written down, eventually, by those who have been troubled by it.” Through their shared experience, she too has learnt that “Knowledge was never a matter of geography. Quite the reverse, it overflows all maps that exist. Perhaps true knowledge only comes of death by torture in the country of the mind.”

A union with the desert of the interior.

© Australian Tourist Commission

The epigraph of Riders in the Chariot is taken from William Blake and suggests connections with Ezekiel and Isaiah, the Chariot itself representing God as divine grace as well as destructive terror and judgement. The corresponding Christ-figure in Riders in the Chariot is Himmelfarb, a Jewish refugee from Germany. Like Voss, he is associated with the element of fire. The other illuminati are equally insignificant from a social point of view: Mary Hare, an elderly spinster; Ruth Godbold, a poor and hard-working housewife; and Alf Dubbo, a part-Aboriginal painter. Himmelfarb’s death by crucifixion on Good Friday suggests that the capacity for evil in Australian suburbia is comparable to its realisation in Nazi Germany as well as in the Bible. Alf Dubbo expresses the unity of the four illuminati in his last painting, which represents the chariot of fire. “Their hands, which he painted open, had surrendered their suffering, but not yet received beatitude.”

The central characters in The Solid Mandala are the elderly twins Arthur and Waldo Brown. Just like Voss and Laura, they are contrary beings, or rather contrasting aspects of the same being, contending but wholly interdependent. In Flaws in the Glass, White claims that the Brown brothers represent his two halves: “Waldo is myself at my coldest and worst.” Mentally retarded Arthur, a Christ-figure like Himmelfarb, assumes the burden of suffering, responsibility and guilt to rescue that other part of himself, and when Waldo dies, Arthur proclaims himself guilty and ends up in an asylum.

The mystery of failure is a common denominator in the novels of the second, religious, phase. As stated in Voss: “The mystery of life is not solved by success, which is an end in itself, but in failure, in perpetual struggle, in becoming”. Similarly, Riders in the Chariot suggests that “atonement is possible perhaps only where there has been failure.”

The third phase

The Vivisector and The Eye of the Storm

The fact that almost five years elapsed between The Solid Mandala and The Vivisector indicates a change of emphasis. A single protagonist is at the centre of both novels in the third phase, and they are dominated by the image of the Eye, which is given a multidimensional function. The central character in The Vivisector is Hurtle Duffield, a painter whose artist’s eye indicates his special instinct, enabling him to discern truth behind appearances. As the title suggests, the eye is also a knife, an instrument of torture. The artist’s fellow-beings must try to protect themselves from “his third eye,” used ruthlessly to vivisect vulgarity, pretentiousness and falsity.

One of his paintings represents the Mad Eye, signifying God as artist, vivisector and opponent. The dual aspect, creation and destruction, the artist as torturer and victim, divine truth as the goal of human will, and human will as subordinate to inevitability, pervades the whole novel. Causing his victims to suffer through his vivisecting eye, the artist must also suffer, but to an even greater extent. Before he reaches illumination, typically through humiliation, his partiality to comparing the artist to God corresponds to Voss’s blasphemous belief in his own divine capacity. Like the explorer, the artist approaches divinity only by becoming human.

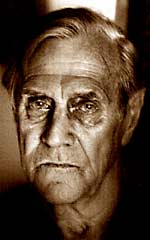

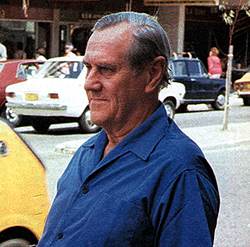

Patrick White at his home in Centennial Park, Sydney. The house figures in “The Eye of the Storm”.

Photo: Ingmar Björkstén, 1973

In The Eye of the Storm, the central character is Elizabeth Hunter, a dying old woman who is almost blind. She is greedy and cruel, and all her life she has consumed others. The title refers to a climactic moment in her life when she was left alone on an island and was caught in a tropical cyclone. The experience implied suffering and humiliation, closeness to death, but also a moment of incredible grace and stillness. Her dying implies a renewed search for that moment of grace, and her deathbed becomes the still centre in all the emotional storms that surround her. To her, as to Hurtle Duffield, the eye comes to stand for the core of reality, the centre of our true existence inside all the layers of appearance. In the end, both protagonists become obedient instruments of the Divine Eye. Their will is wholly concentrated on reaching the eye of truth and infinity, a process that ultimately implies the destruction of that same will. They both make the act of dying a work of art, and the two novels end on a positive note by combining the fundamentally human aspect with the concept of divinity.

The eye stands for the core of reality.

The last phase

A Fringe of Leaves and The Twyborn Affair

The two books representing the last phase deal with the efforts of the central characters to achieve self-discovery. But neither arrives at the kind of illumination that was typical of the earlier books. The religious dimension is toned down in favour of social and psychological ones, and the imagery is less complex. A Fringe of Leaves is a historical novel in the sense that the story of its heroine, Ellen Roxburgh, is based on that of Eliza Fraser, who in 1836 was shipwrecked on a reef off the Queensland coast. She was the only survivor and spent six months, totally naked, with the aboriginal tribe that saved her. In the novel, the idea of nakedness suggested by the title is related to the general message. To the very last, Ellen Roxburgh defends her fringe of leaves, her “gesture to propriety.” She does not, like Voss, become part of the Australian continent in a dying vision of the Southern Cross. Nor does she experience the blessing of sea, sky and land in the way Elizabeth Hunter did. Her return to England suggests that she is withdrawing, physically and spiritually, that she lacks the strength to go to such extremes as White’s true questers do.

In the earlier novels the themes of homosexuality and transvestism are touched upon only incidentally. In The Twyborn Affair they come into focus for the first time. The central character, Eddie/Eudoxia/Eadith Twyborn, has a male body and a female consciousness, and in his search for identity he uses various external disguises, which keep even the reader in the dark. In one section he appears as the young wartime hero, in another he/she assumes the part of Mrs. Trist, the keeper of a fashionable London brothel. He fails to find fulfilment and true sexual identity either as a man or as a woman, but learns to value friendship and the importance of recognising the woman in man and the man in woman. The novel can be read as an enquiry into bisexuality, and sees androgyny as a symbol of wholeness.

An existential pessimist

Taken together, Patrick White’s novels express no specific orthodoxy or conviction concerning existential, mystical or psychological matters, even though it is obvious that he has been inspired by Judeo-Christian mysticism and the philosophies of Eckhart, Schopenhauer, Jung, Buber, and Blake among others. In Voss, for instance, there is a fusion between the more traditional Christian and Dantean aspects, the mystical writings of Meister Eckhart, and the mythological beliefs of the Australian aborigines in a way that is typical of White’s literary technique. In other books, too, we find layers of significance in which White uses various Australian associations combined with archetypal or literary European ones. His attitude is pessimistic in the sense that his successful questers are described as innocent simpletons, isolated or alienated, physically or mentally handicapped, whose final insight is achieved only through ordeals and humiliation. As figures like Voss and Hurtle Duffield show, the explorer/artist is necessarily a sufferer who, in his search for truth, causes others to suffer too. White, like his protagonists, asks himself: “Am I a destroyer, this face in the glass, which has spent a lifetime searching for what it believes, but can never prove, the truth? A face consumed by wondering whether truth can be the worst destroyer of all.”

A face consumed by wondering.

Photo: William Yang

Australia as the country of the mind exemplifies White’s belief that “the state of simplicity and humanity is the only desirable one for artist or for man. While to reach it may be impossible, to attempt to do so is imperative.” In his vocabulary “knowledge” is always unintellectual, irrational and intuitive. It refers to things you “do not know, but know”, to use a wording which, with slight variations, occurs in all his books. He is scornful and sarcastic about the complacent attitudes in those who are satisfied with spiritually limited horizons, those who show no interest in “the mystery and poetry” beyond the Great Australian Emptiness. All his novels demonstrate how will-power, permanence, possessions and safety must be sacrificed. A journey of exploration is always a painful and solitary business through “that solitary land of the individual experience, in which no fellow footfall is ever heard”, as it says in the first epigraph in The Aunt’s Story.

In this division into “the living and the dead”, we are given to understand that there is no rational explanation of why some are granted the experience of unity and illumination, although it becomes obvious that they have a special relationship with the landscape. Thus the desert is said to belong to Voss merely “by right of vision.” In many contexts there is a logical but unresolved tension between the spiritual seeker and the surrounding society. The recurring notions of suffering and loss of self-will indicate that the state in which his questers live is not compatible with an ordinary social existence. Without exception they are described as socially inhibited because of their otherness and the power of their individual vision. An effect of paradoxical elitism is achieved when their outward inferiority and spiritual superiority is portrayed against the background of mental mediocrity and materialism.

Voss’s (and White’s) Australia is a country of infinite distances, unimaginable age and mystery, and the grandeur of this mental landscape is set off against the complacent mediocrity of the masses huddled in the coastal cities. The reason why Patrick White has frequently been accused of elitism seems to be his fierce disdain of the commonplace, his horror of the average, and his contempt for the materialist attitudes of mundane suburbia that are manifest in all his writing. The desert not only assumes the unexpected and unusual nostalgic quality previously mentioned, but at the same time retains its archetypal apocalyptic and daemonic properties. Traditionally a place where deep truths are revealed, it is at the same time a place of suffering and hardship. The enormous distances are used to illustrate the discrepancies between “aspiration and human nature” or between “earthbound flesh and aspiring spirit.”

A mental exploration of the wilderness.

© Australian Tourist Commission

The desert in the centre of the Australian continent, conveniently shaped like a human heart, becomes the Interior with all its interpretative possibilities. The notion of mental exploration is linked with geographical imagery, particularly that of the desert/wilderness. Theodora Goodman becomes a timeless explorer in the wake of Odysseus, and the fact that Stan Parker is named after Stanley, the explorer becomes significant in the context. Voss travels into the desert in Leichhardt’s footsteps and Himmelfarb, too, becomes a desert explorer in his last vision of a journey where “whole deserts were crossed.” Towards the end of his life Hurtle Duffield, the painter, has to reassess what had up till then been the basis of his credo, and to face “the vastest desert he had ever set out to cross: not the faintest mirage to offer illusory solace.” Even the old woman’s death-bed in The Eye of the Storm is a symbolic desert in which she spent years “lying on this mattress of warm moist sand.” Finally her desert, too, takes on its apocalyptic aspects, and she is granted “some miraculous dispensation to feel sand benign and soft between the toes.” At last she herself becomes part of “this endlessness.” Himmelfarb’s death takes place in Sarsaparilla, White’s hellish suburbia, which represents another kind of desert, “the Great Australian Emptiness, in which the mind is the least of possessions”, the recurrent target of White’s satire.

The ultimate paradox is his pessimism as to the possibility of communicating what a single person can perceive.

Photo: Ingmar Björkstén, 1973

To be able to appreciate Patrick White’s consistent but complex structures and imagery the reader must be prepared to enter his symbolic Australia with the open-minded attitude of the explorer or the child. He or she must not demand verisimilitude or logical argumentation, as this is a territory that is usually reserved for poetry. The author’s methods resemble those of a poet, musician or painter. In spite of the fact that White has an idealistic and passionate belief in the power of art and literature to change the world, he claims that he writes only for himself and has “never thought about readership.” The ultimate paradox offered by this paradoxical writer is his pessimism as to the possibility of communicating what any single individual can perceive within his own experience. To thousands of readers, his writing is an entity which consistently explores and communicates his perception of reality. For them, it contradicts the view he expressed above.

Publication of this essay has been made possible through the coordination and assistance of Anders Hallengren.

* Karin Hansson (b. 1937) taught English and Swedish at secondary school level before starting her doctoral studies at Lund University. After completing her doctoral thesis, The Warped Universe: A Study of Imagery and Structure in Seven Novels by Patrick White, 1984, she worked as a teacher and researcher at Lund University and since 1991 at Blekinge Institute of Technology. She was appointed professor of English literature in 1998. She has published literary studies and books, particularly in the field of postcolonial literature, for example Sheer Edge: Aspects of Identity in David Malouf’s Writing, 1991, and The Unstable Manifold: Janet Frame’s Challenge to Determinism, 1996.

She has been a member of the board of EASA (European Association for Studies on Australia). In 1997 she organized a conference on Joseph Conrad and edited the proceedings Journeys, Myths and 1998.

First published 29 August 2001

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.