Transcript from an interview with Derek Walcott

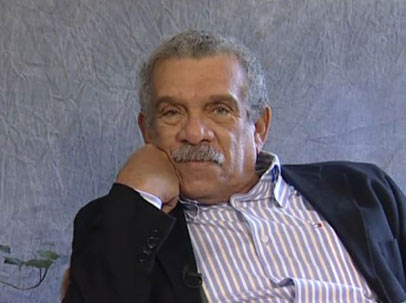

Derek Walcott during the interview.

Transcript from an interview with Derek Walcott on 28 April 2005. Interviewer is freelance journalist Simon Stanford.

Derek Walcott, welcome to the interview. You were the Nobel Literature Laureate in 1992. Tell us where did it all start? What unique combination of circumstances gave Derek Walcott to the world?

Derek Walcott: I’m from the island of St Lucia in the Caribbean in the Lesser Antilles, the lower part of the archipelago which is a bilingual island – French, Creole and English – but my education is in English. I went to St Mary’s College. I was writing from a very, very early age. My father used to write. He died early and my mother was a schoolteacher so my academic background from childhood is a strong one, a good one.

And your ancestry, is it typical of the Caribbean?

Derek Walcott: Yes, a mixed African and Dutch and English, which is probably typical of Caribbean, everybody’s got some mixture of something.

And what does that bring to the culture? What does that bring to you as a writer?

Derek Walcott: St Lucia, which is where I’m from, changed hands from treaties about 13 times, so it might have finished off as a French as opposed to an English island. It’s just the last treaty that made it English, like Martinique, which is its neighbour, or Guadeloupe. What that does is it gives you a bilingual situation, a bicultural situation, very strong African presences there in terms of the rituals, Catholic religion, African rituals and the music is very strongly influenced by African rhythms but of course one studied English literature so all that melange was very fertile for me.

There is a contradiction in the perception of your culture.

Derek Walcott: The usual thing is to see the Caribbean mainly as a tourist place with hotels and waiters and stuff like that and it is, that’s its economic direction, unfortunately, that it has to develop tourism as an industry, so there’s a clichéd perception of the Caribbean as a place of, you know, usual thing, Calypso and steel band and beaches and so on. All of that’s there and it’s true, there isn’t much interest, though, I think in the real Caribbean which is small and negligible in a way, so it’s the Caribbean writers and artists who have made attention happen to the Caribbean, that aspect of the Caribbean, not just the tourist aspect of it.

There’s a recurring theme in your writing.

Derek Walcott: No, the risk that it takes is that it takes a risk of humiliation and embarrassment, in other words if you’re insisted on as someone who should always be hospitable, always smiling for tourists and so on, that’s like a given rule, you know, that is a kind of more benign slavery in a sense, you know? So there’s a big risk of thinking of the Caribbean as a tourist resort, encouraged in a way by government policy of hospitality, but hospitality can be almost taken too far sometimes so I still look out that there isn’t the kind of degradation in that kind of service. I don’t think it’s that bad, but I think it’s risky and of course a lot of the real estate that happens in terms of hotels is often encouraged by the government at the risk of, say, neglecting the needs of the Caribbean people in terms of the villages that are near to beaches, big hotels that are near to poverty. It takes a very delicate balance for it to work.

You write very lyrically, very beautifully, the landscape of the Caribbean, you describe it very, very well but there’s always this tension, so does that give you fertile ground for your writing? This dichotomy, this tension?

The poverty can be exploited sentimentally in terms of presenting certain images that are good for tourism …

The poverty can be exploited sentimentally in terms of presenting certain images that are good for tourism …Derek Walcott: Yes, because again the smallness of the place as that you write, especially in my island, can lead to a very isolated view of oneself. In other words a fisherman, say, working on a beach doing his job, may be photographed by a tourist because it’s photogenic to see him working and the Caribbean is extremely photogenic so poverty is photogenic and a lot of people are photographed in their poverty and sometimes it’s kind of exploited. The poverty can be exploited sentimentally in terms of presenting certain images that are good for tourism, you know, a happy native woman holding up something, a smiling waiter, all of those sort of clichés that one has to avoid, I think it’s almost a duty of the writer to protect the people from that kind of cliché exploitation of them.

In the Caribbean, do you have a readership?

Derek Walcott: I don’t think poetry has a readership anywhere, really, that’s that big. If you go to, say, a poetry reading at the Guggenheim Museum or the YMHA, the full audience might be something like 400, 500. Well, you take a place like New York, with so many million, that percentage of people attending a poetry reading is very, very small and proportionally talking in terms of having a poetry reading in the Caribbean in which you may have 100 people, percentage wise there are more people at that poetry reading in the Caribbean than there at the Guggenheim.

You started, you published very early, you wrote very early. Do you consider yourself a natural writer?

Derek Walcott: I always knew what I wanted to do, which was to write poetry from young, very young, and then later plays, so I knew my vocation extremely early mainly because, I think because of my father’s death, early death, and my mother’s encouragement. My dedication to trying to be a poet started very, very young and I was very well encouraged by good teachers and by older friends and so on, so I think it is a benediction and I also think it is a calling, a duty. For me it was, definitely, and that’s the only thing I knew I wanted absolutely to do from extremely early so that I thought I was blessed as well, too, in fact that I was learning in a society that hadn’t had much expression particularly in terms of English verse, so it was tremendous excitement to paint and to write that early and trying to find out, you know, who you were, what you were trying to write about or who your, people that you are living among are.

And what developed and nurtured your literary voice?

Derek Walcott: My mother was extremely encouraging because she knew my father wrote. My father used to have amateur theatricals done in which my mother was an actress, evidently and his friends and so on, so he had a very small courtier of people devoted to poetry and theatre and stuff like that. So she knew, it wasn’t a surprise to her that I would want to, or my brother, to pursue that calling and to try to be a writer in the Caribbean at that age and, you know, at that time was extremely, well not courageous but a little odd to say, you know, in St Lucia, that you wanted to be a writer when there are no publishing houses and no museums or galleries and so on, but it was good to do it because you were beginning something, you were at the start of something, I thought.

And further to that stimulus, to the stimulus at home and from within your community, a lot of your writing has very sort of deep classical allusions. You’ve written ‘The Odyssey’, you know, you’ve reinterpreted it in your writing so what academic career did you pursue?

Derek Walcott: I have to always defend this idea that I re-wrote ‘The Odyssey’. I think it would be a stupid endeavour to try to do that, so that’s not what it is. It’s a book that has to do with the references, in other words, our references to the classics or to religion or to anything is referential. It is not the direct thing. I mean, our names, our customs and so on, came over the Atlantic and the fact that the Atlantic has an archipelago called the Caribbean and that the Aegean has an archipelago called the Aegean, both are geographical parallels. They’re not cultural parallels, but any fisherman out at sea is an Odysseus and any sort of heroic figure on a beach is a Hector or an Achilles so that these are references. There’s no point trying to do a template of ‘The Odyssey’, that would be a futile exercise. I mean, Joyce did it but he did it with a complete plan of, you know, moment by moment copying of ‘The Odyssey’.

My point of the whole play, of the book, is not to do it in black or to do it in Caribbean, in another language and to use the figures because none of the references are accurate really. They’re all referential, they’re all accidental and therefore they are what we have in the New World which is a sort of half referential, half real reality that someone, an Indian who has lost, you know, India by travelling across, you know, the Indian dispensation of arriving in the Caribbean loses that ancestry too and what remains is a fragmentary memory of accidents and associations and I think that that’s the description of the, not philosophy of the cultural experience that I’m trying to describe. So that it’s not a copy of, it’s in no way a copy of ‘The Odyssey’ to do that because the references are not exact. They are, as I said, referential, they are associative rather than direct.

Is that a privilege that you have, coming from a culture with such diverse origins that you can draw on the association of so many different sources and so many different traditions of …?

Derek Walcott: In a way it’s a misnaming of things rather than a naming so that if somebody sees a black fisherman, you know, striding across on the sand and says: That looks like Achilles, right? He’s obviously not Achilles. The fisherman doesn’t know that he is supposed to be Achilles or anything like that, but the reference that one has made is a carryover from a previous culture whose echoes are carried over into the Caribbean and I think that’s true of Caribbean literature as it is or Spanish-American literature, that these references, these back of the head echoes, are what we try to describe in the New World, not as it was in the Old World, but something associative of the Old World that is there in the New.

What is the African influence in your writing?

Derek Walcott: I think the African influence is in the melody of my voice, I think it’s there in the music that I like, certainly in the plays it’s very strong because it’s a society of percussion, it’s rhythmic in its essence and in the theatre particularly I try to capture that kind of quality that is there in the pulse of the country.

When you write plays, what audiences do you have in mind? You have the audiences that is going to read your dramas but performance must be a very important part of that?

… the audience that exists in these islands is not a brilliant sophisticated audience but it’s the best kind of audience …

… the audience that exists in these islands is not a brilliant sophisticated audience but it’s the best kind of audience …Derek Walcott: Yes. Obviously, I’m very well educated, I read, I write. Consequently, I’m a big difference from someone who is maybe illiterate coming into the theatre, if one can get them in, so that the audience that exists in these islands is not a brilliant sophisticated audience but it’s the best kind of audience because you have to go after it emotionally. You have to move them in the same way that an opera, which we don’t understand, moves us, but they may not understand even the metaphors that are there. Not the metaphors but certainly the language that may be there, but they can be moved by the beat and sway and power of what you’re hoping to write, even more than, say, a naturalistic, you know, three act play in which there’s a linear kind of exposition of something which is rational.

And I prefer to go after something that has more vehemence and more vitality and even if it is not understood but has, in the way that an opera has a visible narrative line, that you can be moved by speeches. I never wrote, I’ve never written down to my allegedly illiterate audience and the fact, the duty to move them is stronger than if I had to do, you know, a play in Stockholm, which has happened, or a play in London or New York. I feel more responsibility to move these people than I feel to try to move an audience in a box like set, you know, in any one of these cities in which you are, you’re going to the theatre and you’re really in a shut box and there’s no sense of light and exhilaration and so on that I like to try to bring to my plays.

In the prelude to your collected poems, there’s a passage: “Until I’ve learned to suffer in accurate iambics”. What does that refer to?

Derek Walcott: Well, that’s a very early poem and I guess what I’m saying is I’m beginning to write and I shouldn’t say anything until I’ve learned how to scan what I’m writing, the technique of writing. The craft, really, is, master the craft and then you can say something and that’s what I’m saying to myself as early as I can.

And where did you go to master this craft?

Derek Walcott: How does a poet teach himself or herself? I think chiefly by imitation, chiefly by practising it as a deliberate technical exercise often. Translation, imitation, those were my methods anyway.

And when do you break away from the roots? Break away from that tree and become truly creative and original?

Derek Walcott: I don’t think I’ve ever tried to be, you know, deliberately original. I mean, there’s a great thing that Pasternak said which is something that I quote often, that I’m not calling myself great, he just says that great poets don’t have time to be original. It’s a great remark. But what one feels, one is part of a huge body of work that you’re trying to contribute to which is on unanimous experience called poetry, even globally and even historically, that there is a thing called poetry which is fed by different languages and your language feeds into that and whatever the language is, there is a limited number of good poems always. There’s always one small anthology of the best poetry that stays the same size for centuries, I think.

Your fellow Laureates on the podium last night have a passion that, to some extent, has been forged and fed by struggle against injustice, by personal suffering. Is there an element of that in your writing? Do you feel a passion that is fed by your awareness of the injustices in your world and in the black world, in the African world?

Derek Walcott: Well, see, to say ‘the African world’ is to confine the experience of the Caribbean strictly to Africa. I don’t like that because I think you have to include the Lebanese, the Syrian, the Chinese, all those people who, from the Mediterranean for instance, have come to the Caribbean, or the Barbadian convict, it is all part of the totality of the Caribbean experience. The emphatic experience probably has been Africa but there’s an equal balance in Trinidad, of say the Indian experience, and I think it’s a duty of the West Indian writers to take in all those different cultures and manifest their experience, even if it may be African or Indian.

I think there’s too much of a separation that goes on now, even, in Caribbean literature of Indian, Chinese and so on and that really the amalgam of everything is a complete experience of everybody being exiled and arriving here and trying to do nicely here, I mean in the Caribbean, and trying to forge something out of it. So that the emphasis, I think, has been very African in the Caribbean, but I’d like to see more presence in Caribbean literature of, say, you know, our writers vary in colour, we have some very good young white West Indian writers, all right? Who shouldn’t be excluded from the idea of the African so called Diaspora because they’re white.

You talk about the rhythm, the percussion of Africa, of the Caribbean; you talk about that sort of cadence that comes into your writing. Is there a continuity into the present that you pick up through reggae, through hip hop, through a constant evolution of poetry?

Derek Walcott: Not so much poetry, I don’t think. I think more music, I think, you know, there’s a lot of poetry coming out of Jamaica, that kind of sort of public poetry. That goes on, like rap and stuff like that, you know, but I think you have to kind of make a distinction between poetry and that kind of performance because very often it is too monotic, too boring, you know, too repetitive to the industry, I think. But I think in the theatre that the young actors, for instance, we have a group of actors coming out of that background who can take in the idea of playing Shakespeare as easily as if they can do a rap number, so that mix is great.

Is there a valuable contribution that is evolving all of the time? That adds to the body of influence, though?

Derek Walcott: I think the manifestation, as always in literature or culture, is music, what’s happening to the music? And what’s going on in Caribbean music is, I think, pretty phenomenal because it takes in all these different strains and makes it one thing. I think I like Zouk a great deal because it has polka in it and it has reggae. It’s sort of a amalgam, which is what the Caribbean culture is and that’s manifested in the music, so in that sense it can be made theatrical by manifesting it physically. To have that … I think what’s happening, I think that presence, that combination of different sources and different elements mixed together which some people might think as degenerate and corrupt because it’s not authentic and steady, but that’s the manifestation of Caribbean experience and it is that multi cultural and multi faceted and great for a writer, experience a playwright.

Are you a very sensitive observer? How do you as a writer get into the human experience and express it through different viewpoints and different characters?

Derek Walcott: The novel tends to do that more than, say, theoretically the poem, although you can do it in long poems, so I’m talking about the technique of whatever you’re doing and what you’re using to justify, you know, your existence as a writer. And the theatre, I think, does that because the joy of the theatre, of course, is to have a new people to write about, the Caribbean people, and to write about them not only on one level of, say, the tourist level of the level of the forest or beach or whatever but also to examine a little more carefully what the Caribbean middle class is about. We need more plays of that kind, that examination of what is the structural conflict that, not structural conflict but the cultural things that can go on in the class war that happens which is more real than, say, a racial context. A class examination of what is happening in the Caribbean now, I think, is an exciting subject.

Have you written about this? What of your writings explores this particular theme of class?

… what I try to maintain is the melody that’s my own melody …

… what I try to maintain is the melody that’s my own melody …Derek Walcott: I write in verse, so I don’t think I’m moving from poetry when I enter theatre so that I try to have the same complexity that you might get in a poem as you might get in, say, the equivalent of a dramatic aria of someone talking, so it is for me a matter of meter as much as it is a matter of structure so even if it’s middle class language, what I try to maintain is the melody that’s my own melody, the way I’m talking now, and how far it can carry itself into something that may be metaphoric or, you know, discursive and its manifestation in terms of dialogue and that’s there, I think it’s an extremely enriching place to be for a writer now.

Is it accessible? Do you feel that your writing is accessible to a broad audience or, as you say, is it, you know, poetry readings don’t attract huge …

Derek Walcott: No, it’s not accessible at all, in fact it’s far from accessible because first of all the subjects that I’m writing about are not of interest to anybody on Broadway. They don’t care about the life of a black fisherman, you know, if that’s what I’m writing about, or the life of an Indian woman living in the country or something, because those are not box office subjects. So we have to be, we have to move away from the possibility of hoping that, you know, you’re going to have a hit on Broadway in which you’re dealing with peasants or backward people or under developed people so that’s that theme, that possibility just has to be erased and fact is good because then you don’t take your theatre in that particular direction.

You take it in the direction it should go in the reality of what you’re writing about, but the temptations are there and the temptations remain, the Hollywood temptation and the Broadway temptation and the commercial temptation. It’s there for the novelist as much as it is for the playwright. You know, you don’t sell sonnets to Warner Brothers for production but it’s also, in a way, it’s there for the poet as well. The great threat is that whole commercialisation of art that has happened in the 20th century because people can make tremendous fortunes from writing, with luck. They can, you know, and sometimes I think that particularly in America, that’s very present in terms of a young writer who can make a tremendous fortune if they have a hit book, a hit you know, anything, so that’s a dominating fare that’s there.

Since that’s not present in the Caribbean, then you feel freer to do what you want without always being haunted by the idea. You know it’s not going to be a hot, there’s no chance of it being a hit, so there’s a little more likelihood of one being a little more truthful to the experience than glamorising it into something that might make a lot of money.

So you consider that sort of predominant commercialisation is a threat to integrity?

Derek Walcott: More and more, yes. I can only say the obvious in terms of television or what television does, not to the audience, but to the writer. I don’t think there’s a writer in the 20th century who can escape the idea of a hit, of making a million dollars not deliberately but by accident, even, you know, that that possibility remains there and it grows more and more corruptible in the sense that the, you know, we now pay actors $20 million to make a movie. That’s a budget of a small island, you know? So the sense of proportion is very threatened everywhere.

You write epic poetry. You wrote ‘Omeros’. I mean, that is not a popular current form at all.

Derek Walcott: Yes, I wish they’d make a movie and pay me 20 million though. Despite what I’m saying.

What lies behind that? What stimulates you to sit down and write epic poems?

Derek Walcott: I don’t like, I’ve said it before, I’m not crazy about the word epic because it has such a pompous echo to it. It’s a long book and I guess it’s epical in the sense that the Caribbean experience has been epical, the middle passage is epical the, you know, Indian journey across from India to here, the piracy, the different things that have happened in the Caribbean, but what that particular book, what made me want to continue daily and enjoy working on it every day was, the propelling thing was celebration.

I wanted to celebrate the island and the people that I knew so at the back of it there was a joy of responsibility in doing it that, you know, made me want to get up in the morning to work on it. Plus, of course, the form. The form was exciting because I had to write rhyming hexameters alternating with whatever, you know, in a terza rima design, you know, it was a challenging thing to do and it was, because it was formal in that respect, then it was exciting to get up to do it. I guess like going to play golf. I don’t play golf, but it must have been the same thing every day.

What do you say to a potential reader?

I think poets now don’t give delight to readers, they give responsibility.

I think poets now don’t give delight to readers, they give responsibility.Derek Walcott: Well you hope, in a work like that, you hope that you’re engaging the reader and this is very pompous but I mean in terms of delight, in terms of giving delight to the reader. I don’t think that’s something that’s around now. I mean, I think poets now don’t give delight to readers, they give responsibility. They make things very hard for the reader and it’s like a test, it’s an examination. Nearly every poem you read now is like an exam, you know, try to work out what it’s saying.

A few more things, the Nobel Prize, of course, I mean, you talk about having a hit. How did you get to find out that you were a Nobel Prize Laureate and what was your reaction?

Derek Walcott: I had heard rumours about it the year before I got it and that tends to happen, I think, to candidates. You know, their names keep coming up. I forgot exactly now, but somebody called me, obviously, and they called me early in the morning and I was at home alone and it was a shock, a very pleasant shock. Sort of a shock. I kind of thought well maybe, yes, it could happen, you know, and when it did it was from that day on the pace of being a Nobel Prize winner increased tremendously. I mean, as Czeslaw Milosz once said to somebody who had won the Prize, I’m sorry for them, in the sense that the harassment is not a good word but the press, who dutifully have to do what they do, like call you up and find out and all of that, so, I mean, the phone was interminable, it just kept going and so on.

On the other hand, though, you recognise what a tremendous honour it is and what good it can do or has done or could do for Caribbean literature, you know. It was not for me only but it felt like it was doing something for what has been happening in Caribbean writing and Naipaul is a candidate, an obvious candidate that I have nominated anyway. As much as I don’t like a lot of the stuff that he writes, but I have great respect for him as a writer, so I would nominate him every time it came up that he would be nominated and I’m glad he finally got it, even if he behaved a little stupidly once he did get it.

So did you see yourself at that point as a standard bearer for Caribbean literature?

Derek Walcott: No. What did happen, though, was extremely moving. There was great celebration and what one had to do was to separate yourself from the celebration in a way, that you had to make yourself, translate yourself into the third person, right, like, oh they’re applauding him as opposed to, you know, oh they’re applauding me or they’re creating something around me. You’ve got to eradicate the me and make it a third person thing for the sake of, I think, the Prize is given to the idea of poetry as much as it is to the poet himself, to the perpetuation of poetry is what I think the prize means.

Finally, young writers, do you have something special that you can say to aspirant young writers?

Derek Walcott: I teach at Boston University and I have young poets that I am supposed to be guiding in certain directions and I’ve always have a lot of pleasure and pain too in trying to direct them in certain ways because it’s very painful sometimes to see a young artist trying to shape his or her life and to wonder what to tell them, which is in a way what, you know, you try to do in the sense of saying you better make very sure that this is what you want to do because it’s going to be extremely demanding and you probably will give up and that’s sad because eventually they do give up, some of them, because different things come into their lives.

Often for young women it’s marriage and sometimes I would say, you know, get a boyfriend who understands what you want to do but don’t give up what you’re doing for the boyfriend or for the husband because this is a calling and that’s the, not penalty, but that’s the thing that comes with the calling and the same thing might be true of a young man, saying that, you know, especially if you want to do poetry all your life and that you think this is what your life should be, it’s very painful sometimes to look at that happening under your tutorship.

So it is a calling? You need to be prepared to sacrifice?

Derek Walcott: In a way, the ones who aren’t called or driven, when they give up, it may be best that they did give up but sometimes I have seen those who should not give up surrender from time, from other things that come in their way, you know, the concept of, say, being a writer and making a living off a writer, especially a young playwright, it’s very, very hard for young American playwrights, extremely hard. There’s no body of production to support them. There’s not a state theatre, there’s no provision for, well there’s social security, I guess, but I mean it’s not like Europe where you can have an idea of a candidacy of being a playwright in a state theatre and so it’s abysmally lacking here. Very frightening.

Thank you very much for being with us.

Interview with the 1992 Nobel Laureate in Literature, Derek Walcott, by freelance journalist Simon Stanford, 28 April 2005.

Derek Walcott talks about his Caribbean background; his early vocation to become a poet (6:17); what audience he writes for (12:58); influences from the Caribbean culture (17:12); the commercialisation of culture (24:14); what inspired him to write Omeros (27:19); being awarded the Nobel Prize, (29:40); and gives advice to young student (32:42).

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.