Award ceremony speech

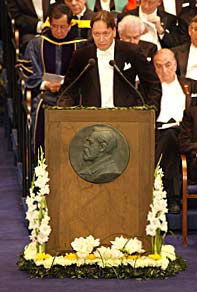

Presentation Speech by Horace Engdahl, Ph.D., Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, December 10, 2001.

Translation of the Swedish text.

Dr. Horace Engdahl delivering the Presentation Speech for the 2001 Nobel Prize in Literature at the Stockholm Concert Hall.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2001

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Honoured Nobel Laureates, Ladies and Gentlemen,

In the Middle Ages, master craftsmen worked in full view in the street or in an open workshop, so that prospective buyers could see that the materials they use were geniune and that no defects were hidden beneath a luxurious surface treatment. Similarly, as a mature writer V. S. Naipaul has allowed us to scrutinize his craft and the conditions surrounding it. He has candidly described how, as a beginner, he neglected to obtain knowledge of what he saw and falsified his experiences in order to live up to the perception of literature he had gained through his British schooling.

He knew at an early age that he had to write, but not what. His first book, The Mystic Masseur, appears very bold when read in the light of his confessions about the awkward beginnings of his own career as a writer. The masseur/charlatan is the author’s shadow and caricature, to which he exorcistically transfers his bizarre traits and imagined failures, something like Sartre did with the autodidact in La Nausée.

Naipaul was born on the West Indian island of Trinidad as a descendant of immigrant workers from India, in a milieu where peoples and cultures from four continents mixed. In his case, moving into literature presupposed irrevocably breaking away from these origins. Yet it was not until the moment when he decided to explore what he had abandoned that his writing took off. His childhood street set the tone for him. At first it was playful and immediate, but the subject grew in his hands. In the book that made him famous, A House for Mr. Biswas, he lent the profundity of the major novel to the wing-clipped characters in a Caribbean backwater and granted them dignity. Mr. Biswas, who bears traits of Naipaul’s father, gained a place in the English literary gallery of immortal tragicomic heroes.

Naipaul’s subsequent works examined, in ever wider circles, the forgotten historical circumstances that explain the author’s background. He became an explorer, not of the wilderness but of societies – everywhere at home and a stranger, a Ulysses whose only Ithaca was his desk. Perhaps he is a witness from the freely circulating humanity of the future.

Naipaul has been praised for writing the best English in the market, and that may well be, but his view of style is reminiscent of Stendahl’s, who believed a writer has failed if the reader remembers the words he has written: what should remain are his ideas. Naipaul is no worshipper of fantasy or utopia, no creator of alternative worlds. Dickens’ ability to describe London with the open gaze and simplicity of a child is his declared ideal. He continues a critical direction in literature that distances itself from myth and expressive hyperbole. His text is permanently unrelenting, like a chill wind that will not stop blowing.

In Reading and Writing, an essay of great value in understanding his works, Naipaul relates his steadily growing doubts about the novel, the grand genre of the West. He describes how while working on his history of Trinidad, The Loss of El Dorado, he found in the archives traces of the native tribe that had given its name to the small city where he spent his first years, and how his perception of reality suddenly expanded. “Fiction by itself would not have taken me to this larger comprehension,” he writes. The technique he adopted while working on El Dorado – unearthing from the documents the life stories of seemingly insignificant individuals – returns when he works with the notes from his journeys. The various literary forms he has tried – fictional narrative, autobiography, feature story and historical documentary – have eventually merged into a unique genre, “prose in the style of Naipaul”. By this innovation, he has enlarged the territory of literature.

One experience that seems to have been crucial to his literary method is his first encounter with India. He saw traces of a history that had been concealed from view when the champions of independence had to deny the misfortunes that had preceded the English: six hundred years of Muslim imperialism that deliberately destroyed the memory of earlier civilisations and plunged the Hindus into a helplessness similar to that of the American Indians. He studied R.K. Narayan’s novels in the Indian setting and saw that their world is built around an emptiness that the author is incapable of dealing with: the forgotten defeat that turned people into dwarves among monumental ruins. Only an intact culture provides the background knowledge that makes the novel a reasonable form, Naipaul argues. He found that he had to cling to the authenticity of details and voices and abstain from fabulation, while continuing to give his material a literary shape. He became a collector of testimony.

This method presupposes the courage to seek out human phenomena that frighten every normal observer, the author included. But even when he reports from places where no hope seems to exist, the author’s empathy makes itself felt in the acuity of his ear. He says he finds every person interesting, at least for the first few hours. He distinguishes individual fates beyond the dutiful idealization that controls our perception of the earth’s ill-fated nations. He wants to understand the principle of every person’s life, the decisive thing that makes him what he is. He records the relationship between pretension and reality, two contours that never really cover each other and never completely diverge.

Decay and disappearance are a fundamental theme in Naipaul’s writings – but without grief, rather as something that makes existence bearable. The English landscape that he discovers in The Enigma of Arrival is the ruin of an age of greatness, and at last he feels at home! He says that even as a child, he has pondered that he was born into a world past its climax. Yet his books are not negative. His phrasing embodies an absence of resignation that keeps melancholy at bay and shares with the reader the pure joy of intelligence.

Naipaul has praised the West for having recognized the right to individual endeavour and for its diffidence. The core of his devotion to European civilisation is that it was the only one of the alternative cultures that made it possible for him to become a writer.

Sir Vidia!

Your life as a writer calls to mind what Alfred Nobel said of himself: “My homeland is where I work, and I work everywhere.” In every place, you have remained yourself, faithful to your instinct. Your books trace the outline of an individual quest of unusual dimensions. Like a Nemo piloting a craft of your own design, without representing anyone or anything, you have manifested the independence of literature. I would like to convey to you the warm congratulations of the Swedish Academy as I now request you to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.