Award ceremony speech

English

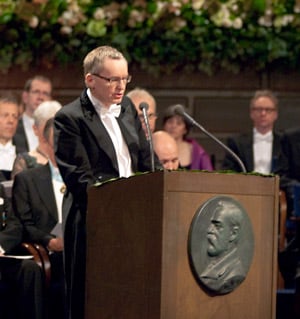

Presentation Speech by Professor Anders Olsson, Member of the Swedish Academy, 10 December 2009.

|

| Professor Anders Olsson delivering the Presentation Speech for the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature at the Stockholm Concert Hall. Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009 Photo: Hans Mehlin |

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Some literature reveals its deep qualities slowly, step by step. Other literature captures the reader immediately by its resolute address. Herta Müller’s work belongs in the latter category. Her prose has a linguistic energy that we bond with from the first sentence. Something concerning life or death is at stake. We sense this quickly through the temperature, the hurried breathing, the sharp detail, and everything implied but left unsaid.

This energy springs from a refusal to accept what is. Herta Müller chooses opposition as method, making common cause with the Austrian author, Thomas Bernhard. But, even more strongly than Bernhard’s, her work is anchored in her own experience. She has said that her subjects have chosen her, not the other way around. Almost everything she writes is about life under Ceauşescu’s Romanian dictatorship, its fear and betrayal and constant surveillance.

But Herta Müller has also portrayed a kind of dictatorship within a dictatorship: the small, German-speaking rural society in western Romania where she grew up. We enter it in her first book Niederungen, 1983 (Nadirs, 1999) a suite as cruel as luminous images to a child’s gaping senses. Out steps an alien ego, its alienation also self-induced through a transformative, critical gaze. In the visionary short prose of Barfüssiger Februar from 1987, a dream image such as the black axis deep down at the bottom of the well captures, with hallucinatory strength, the way a village existence orbits life and death.

Quickly, the exposition of alienation widens into the Romanian dictatorship in general. This happens especially after Herta Müller is forced into exile in Germany in 1987 after years of censorship, interrogation and harassment. It can be said that in her case, exile serves to sharpen the confrontation with dictatorship. This occurs in novels such as: Der Fuchs war damals schon der Jäger from 1992, with its shining series of images of everyday terror; Herztier, 1994 (The Land of Green Plums, 1996) a masterful account of the flight of a group of youths from the terror regime; or Heute wär ich mir lieber nicht begegnet, 1997 (The Appointment, 2001) a fractured, chilling thriller in the shadow of imminent interrogation.

Herta Müller’s experience of oppression leaves her no peace. But central to her art are figures of opposition. In a famous essay, Claudio Guillén coined the word ‘counter-exile’ for writers not defeated by exile through nostalgia. For Herta Müller, doubly rootless, return is an impossibility. The nostalgia is unconscious, flickering through only in the shape of a lone apricot tree on an embankment, so foreign in Berlin’s northern latitudes. As so often, objects show Herta Müller a direction. They play a major part in her prose, because their shadow-side points to the labyrinths of fear.

Herta Müller has said that her German-speaking upbringing in Romania has been a great inspiration to her writing. For a writer it can be invaluable to have two different languages, and from this situation she early learned to compare, to turn and twist words to extract new meanings.

You find, in Herta Müller’s prose, no epic line, no plot with beginning and end. If the world is ambiguous and opaque, literature must cease to provide a deceptive overview of it. She has said that only fictional surprise allows us to approach reality. She scissors out bits of experience to subsequently amalgamate them, and she has also used collage as a method to write poetry. In her essay collection, Der König verneigt sich und tötet from 2003, an indispensable guideline to her authorship, she explains that she finds no conclusive difference between poetry and prose. Her individuality as a narrator resides in just that ability to marry poetry’s density with the feel for detail in prose. She does this in crystal-clear syntax, where every clause demands our attention.

With infinite empathy and unsentimental eye, she prolongs her counter-exile in her great novel Atemschaukel from 2009, about the deportation of Romanian-Germans from the year 1945 and their forced labour in what was then the Soviet Union. Here, she is pursuing the project planned with her close friend, the poet Oskar Pastior, who died in 2006. When young, Pastior had been in a Soviet camp. Even here, in stronger dependency than earlier on documentary material, she succeeds in uniting the lucidity of prose with the shock impact of poetic imagery. In the vivid coinage of the title, Atemschaukel, translatable as “Breathswing”, she is heir to the great Romanian-German exile poet Paul Celan, who could call one of his collections Atemwende, “Breathturn”. In intensive, intermittent episodes from camp life, she gives a segment of unavoidable contemporary history renewed visibility.

Liebe Herta Müller.

Sie haben den großen Mut gehabt, der provinziellen Unterdrückung und dem politischen Terror kompromißlos Widerstandzu leisten. Für den künstlerischen Gehalt dieses Widerstands verdienen Sie diesen Preis. Ihr Werk ist ein Kampf, der weitergeht und weitergehen muß, eine Form des unwiderruflichen Gegen-Exils. Und obwohl Sie gesagt haben, daß Sie das Schreiben vom Schweigen und Verschweigenlernten, haben Sie uns Wörter gegeben, die uns unmittelbar und tief ergreifen – mit dem Schweigen, über das Schweigen. Ich möchte die wärmsten Glückwünsche der Schwedischen Akademie aussprechen, wenn ich Sie jetzt auffordere, den Nobelpreis für Literatur aus der Hand Seiner Majestät des Königs entgegenzunehmen.

Dear Herta Müller.

You have shown great courage in uncompromisingly repudiating provincial repression and political terror. It is for the artistic value in that opposition that you merit this prize. Your work is a labour that continues and must continue a form of irreversible counter-exile. And even though you have said that silence and suppression taught you to write, you have given us words that grip us deeply and directly – in silence and beyond silence. I would like to express the warmest congratulations of the Swedish Academy as I now request you to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.